Why do we meditate on impermanence? Why does Buddha speak so often in Sutras, on the “poison” of anger? Why do we see so many “angry” or even demonic Enlightened Buddhas in Mahayana and Vajrayana? In this feature, we discuss nine remedies for the poison of anger — from all traditions of Buddhism — and include three entire sutras (in English) on related topics, including:

- Discourse on the Five Ways of Putting an End to Anger

- Akkosa Sutra: Insult

- Vitakkasanthaana Sutta: The Discursively Thinking Mind

One of the most important missions of a practicing Buddhist is to transform the “poison” of anger. Anger is perhaps the most dangerous of the Buddhist “kleshas”, or poisons. For this reason, there are more practices in all schools and traditions of Buddhism for resolving, pacifying and transforming anger than any other of the principal kleshas or poisons: which include anxiety, fear, anger, jealousy, desire, and others.

Pithy advice from Buddha

Gautama Buddha and sutras and much to say on anger, from the simple to the complex, starting with pithy advice from Buddha in the Dhammapada (v 233):

“Conquer anger by non-anger. Conquer evil by good. Conquer miserliness by liberality. Conquer a liar by truthfulness.”

Anger is one of the great obstacles in Buddhist practice — and in daily life. The very heat of anger obscures our minds — and not just our own minds, but those we touch: online at Facebook or Twitter, those we interact with at work, and our relationships at home. Anger is contagious and dangerous.

Anger an “Out of control forest fire”!

In Buddhist teachings, anger is most often metaphorically compared to either an “out of control forest fire” or a “rampaging elephant.” Why these two? Simply because anger reacts and destroys quickly; we often don’t have time to control it — it tends to explode destructively outwards: angry words that hurt, angry fists that bruise, angry weapons that kill, angry actions that destroy relationships, angry reactions that destroy business deals.

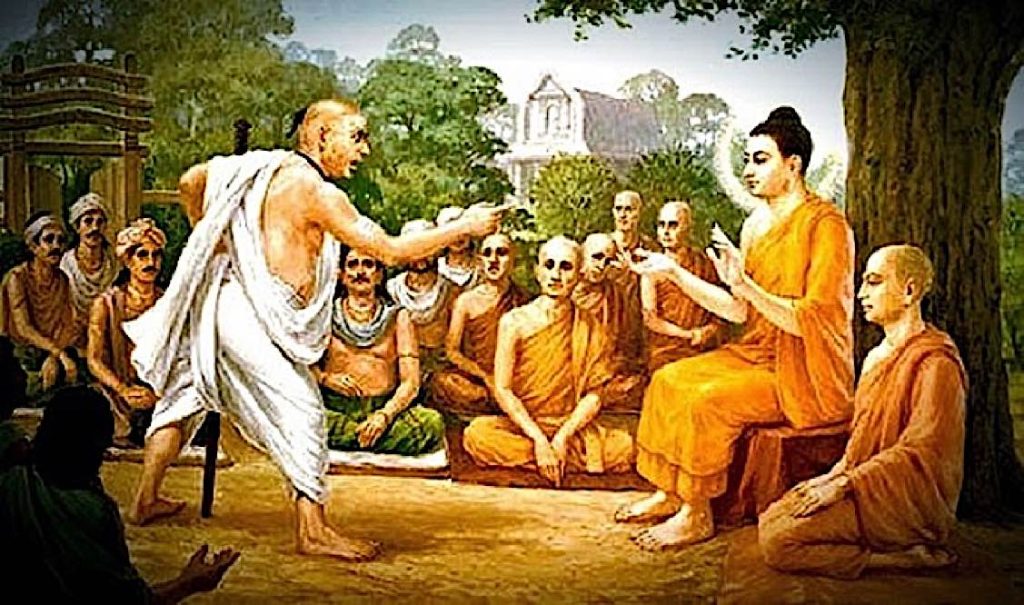

It is worth remembering the story of Buddha calming the “rampaging elephant” with a simple gesture and a peaceful demeanor. With practice, the quiet, patient mind can overcome the destructive flash of anger.

Nine ways to end anger

Although Sutras discuss solutions to anger in great detail (see three full sutras below), the recommendations of the Buddha can be thought of as these five, led by mindfulness, which is chief among all anger-management solutions:

- Meditate mindfully in the present moment: Observing anger but not participating in it (Even psychotherapists use mindfulness to help patients manage anger.)

- Practice Metta and Karuna (Loving Kindness and Compassion): be attentive to the kindness of others, and overlook their unkindness. Practice metta kindness and compassion for all beings, putting your enemies first in your meditations

- Practice wisdom and discernment: (which includes patience, a form of wisdom). Analyze anger meditatively, understand its cause and effect; approach problems with patience — with time, anger fades

- Substitution method: Substitute something positive for the negative. In other words, if a person’s action angers you, analyze the person to find the positives you can focus on. (For example, a police chief angers a community because of a “no leeway” rule on traffic tickets; but if you analyze the police chief you see that your community has the lowest crime rate in the area.) In Tantric practice, substitution becomes “conversion” where afflictive emotions are converted into positive action and practice. (Classically, Yamantaka wrathful deity meditation for anger.)

- Meditate on impermanence: Nothing makes anger seem more unimportant than understanding death can take any of us, at any moment. It also helps us understand that anger itself is rising and falling, and impermanent.

- Truly comprehend Shunyata, Emptiness and Oneness: When we understand that ego is the only thing that separates us from “other” — that we are all One in this Universe — the very thing that gives rise to anger is gone. Ego, is the author of anger.

- Understand anger is your teacher: We’re here, in samsara, trapped by our poisons. When we take our poisons as our teacher — if we can learn from our anger, and the anger of others — we transform the anger into the path.

- Meditate on Karma: anger has repercussions. Remain mindful of karma in all of your activities. Anger inevitably leads to a downward and accelerating cycle of destructive karma.

- Practice transformation and Tantra visualizations: Tantric meditation — visualizing the emptiness of a phenomenon and practicing Yogic methods — are one of the fastest ways to transform anger, hate, greed, delusions or any other poison into the path. By personifying “anger” for instance, then transforming it into an “Enlightened form” we train our mind to transform the poison permanently.

Mahayana: Wisdom Solutions and Compassion Solutions

Or, you can think of this in Mahayana terms — wisdom solutions and compassion solutions. Wisdom solutions would include:

- mindfulness practice (even “live” on that angry phone call or meeting)

- analysis of anger meditation

- practicing patience

Compassion solutions would include:

- metta and loving kindness meditation

- substitution method: think of the positive aspects of a person or situation, to help put the negative in perspective.

It is worth reading through the three sutras in this feature. Those are the precious words of Dharma; no greater advice can be offered.There are also solutions to anger contained in Tantra (for example, Yamantaka practice is very powerful for “angry people”; or Chod practice, where we “feed our Demons.) All Buddhist traditions have extensive teachings on anger.

Karmic Consequences are Real

Still simmering from the latest fight at work or argument at home? Finding a quiet mind that evening, during your mindfulness session, may become elusive. Worse, if the anger gains momentum, there can be very negative karmic consequences. Regret only goes so far if your rage has already hurt someone. Then, there is the very real karmic consequence of “retribution.”

The Dalai Lama said, “Violence is old-fashioned. Anger doesn’t get you anywhere. If you can calm your mind and be patient, you will be a wonderful example to those around you.” [2]

A careless angry comment on Facebook can lead to hurt feelings — even dire consequences in the case of a clinically depressed person. Words expressing anger have ferocious power to damage, hurt, even kill. Anger leads to fights, accidents, homicides and war. And, in our daily practice, it makes a settled, peaceful mind nearly impossible. Or, it can just make you feel really lousy for weeks.

Sutric Solutions: Discourses on Anger

Many discourses and Sutras (Sutta in Pali) touch on anger, notably, the Madhyama Agama No.25 (full text with translation by Thich Nhat Hanh below) and the Akossa Sutra (full text also below.) Also, the Vitakkasanthaana Sutta (below.) To summarize, though, we can distill the Buddha’s methods down to five key recommendations that really work, even today, in our modern, chaotic, angry world.

Great masters such as Shantideva also taught anger management: “Anger is the greatest evil; patient forbearance is the greatest austerity.” The great teacher, and author of Bodhicharyavatara, basically informs us that forbearance and patience are a greater and more challenging austerity than fasting, prayers, practice, pilgrimages.

In other words, it isn’t easy to manage anger.

What Causes Anger from a Buddhist Point of View?

Buddhism is always about cause and effect. Karma is basically defined that way. How did Buddha describe the cause of anger? Lama Surya Das explains:

“The main klesha that fuels this whole dualism of attachment and aversion which drives us is ignorance, or delusion and confusion. From ignorance comes greed – avarice, desire, lust, attachment and all the rest. Also from ignorance comes anger, aggression, cruelty and violence.”

He goes on to explain: “These two poisons are the basic conflicting forces within us—attachment and aversion. They come from ignorance, and they’re really not that different: “Get away” and “I want” are very similar, just like pushing away and pulling towards; and both cause anger to arise. Anger is often singled out as the most destructive of the kleshas, because of how easily it degenerates into aggression and violence.”[2]

Psychology of Anger from a Buddhist Point of View

Buddhist teachings often align with psychotherapy and Psychiatry. Anger teachings certainly directly line up. Lama Surya Das explains: “anger is easily misunderstood. It is often misunderstood in our Buddhist practice, causing us to suppress it and make ourselves more ill, uneasy and off balance. I think it’s worth thinking about this.

Psychotherapy can be helpful as well. Learning to understand the causal chain of anger’s arising as well as the undesirable, destructive outflows of anger and its malicious cousin hatred can help strengthen our will to intelligently control it. Moreover, recognizing the positive sides of anger – such as its pointed ability to perceive what is wrong in situations, including injustice and unfairness – helps moderate our blind reactivity to it and generate constructive responses.” [2]

Buddhist psychology does differ in depth, however. As Ani Thubten Chodren explains:

“Science says that all emotions are natural and okay, and that emotions become destructive only when they are expressed in an inappropriate way or time or to an inappropriate person or degree….Therapy is aimed more at changing the external expression of the emotions than the internal experience of them. Buddhism, on the other hand, believes that destructive emotions themselves are obstacles and need to be eliminated to have happiness.”[2]

Mindfulness Always Works

Ultimately, mindfulness is the most-often recommended method. The often cited: “the past is gone, the future is not here yet” thought, combined with relaxing the mind into an observant state where we observe only the present moment. If angry thoughts arise in our meditation, we observe rather than react. Although it’s “easier said than done” it really does work. For this reason, daily mindfulness practice is a good strategy. This way, when needed to help us resolve anger, we can draw on well-practiced technique. There are even business books that teach how to be mindful during an “angry” meeting, how to retain control and manage emotions dynamically. Buddha, of course, taught these methods more than 2500 years ago.

Equally, Metta meditation, a Mahayana Buddhist practice, is very powerful as a remedy. If we practice compassion and kindness to all beings, on a daily basis, when faced with “evil” behavior, we are more likely to feel compassion instead of hate or anger. Metta affirmations do not say “May some beings be happy and free from suffering.” It says, “May ALL beings be happy.” This, includes our enemies.

Substitution, Analyze and Ignore Methods

One method to overcome the Discursive mind, explained in the Vitakkasanthaana Sutta (full text below), was explained by the Blessed One:

“The Bhikkhu attending to a certain sign if evil Demeritorious thoughts arise conductive to interest, anger and delusion, he should change that sign and attend to some other sign conductive to merit, then those signs conductive to interest, anger and delusion fade, and the mind settles and comes to a single point.”

The rest of the Sutra then explains what to do if the substitution doesn’t work, which break down into:

- analyze the anger: “When the dangers of those thoughts are examined those evil de-meritorious thoughts conductive to interest, anger and delusion fade.

- ignore the anger: ” When those evil de-meritorious thoughts conductive to interest, anger and delusion are not attended, they fade. With their fading the mind settles and comes to a single point.”

Discourse on the Five Ways of Putting an End to Anger

Translation by Thich Nhat Hanh from the Madhyama Agama No. 25 [1]

I heard these words of the Buddha one time when he was staying in the Anathapindika Monastery in the Jeta Grove near the town of Shravasti.

One day the Venerable Shariputra said to the monks, “Friends, today I want to share with you five ways of putting an end to anger. Please listen carefully and put into practice what I teach.”

The bhikshus agreed and listened carefully.

The Venerable Shariputra then said, “What are these five ways of putting an end to anger?

“This is the first way. My friends, if there is someone whose bodily actions are not kind but whose words are kind, if you feel anger toward that person but you are wise, you will know how to meditate in order to put an end to your anger.

“My friends, say there is a bhikshu practicing asceticism who wears a patchwork robe. One day he is going past a garbage pile filled with excrement, urine, mucus, and many other filthy things, and he sees in the pile one piece of cloth still intact. Using his left hand, he picks up the piece of cloth, and he takes the other end and stretches it out with his right hand. He observes that this piece of cloth is not torn and has not been stained by excrement, urine, sputum, or other kinds of filth. So he folds it and puts it away to take home, wash, and sew into his patchwork robe. My friends, if we are wise, when someone’s bodily actions are not kind but his words are kind, we should not pay attention to his unkind bodily actions, but only be attentive to his kind words. This will help us put an end to our anger.

“My friends, this is the second method. If you become angry with someone whose words are not kind but whose bodily actions are kind, if you are wise, you will know how to meditate in order to put an end to your anger.

“My friends, say that not far from the village there is a deep lake, and the surface of that lake is covered with algae and grass. There is someone who comes near that lake who is very thirsty, suffering greatly from the heat. He takes off his clothes, jumps into the water, and using his hands to clear away the algae and grass, enjoys bathing and drinking the cool water of the lake. It is the same, my friends, with someone whose words are not kind but whose bodily actions are kind. Do not pay attention to that person’s words. Only be attentive to his bodily actions in order to be able to put an end to your anger. Someone who is wise should practice in this way.

“Here is the third method, my friends. If there is someone whose bodily actions and words are not kind, but who still has a little kindness in his heart, if you feel anger toward that person and are wise, you will know how to meditate to put an end to your anger.

“My friends, say there is someone going to a crossroads. She is weak, thirsty, poor, hot, deprived, and filled with sorrow. When she arrives at the crossroads, she sees a buffalo’s footprint with a little stagnant rainwater in it. She thinks to herself, ‘There is very little water in this buffalo’s footprint. If I use my hand or a leaf to scoop it up, I will stir it up and it will become muddy and undrinkable. Therefore, I will have to kneel down with my arms and knees on the earth, put my lips right to the water, and drink it directly.’ Straightaway, she does just that.

My friends, when you see someone whose bodily actions and words are not kind, but where there is still a little kindness in her heart, do not pay attention to her actions and words, but to the little kindness that is in her heart so that you may put an end to your anger. Someone who is wise should practice in that way.

“This is the fourth method, my friends. If there is someone whose words and bodily actions are not kind, and in whose heart there is nothing that can be called kindness, if you are angry with that person and you are wise, you will know how to meditate in order to put an end to your anger.

“My friends, suppose there is someone on a long journey who falls sick. He is alone, completely exhausted, and not near any village. He falls into despair, knowing that he will die before completing his journey. If at that point, someone comes along and sees this man’s situation, she immediately takes the man’s hand and leads him to the next village, where she takes care of him, treats his illness, and makes sure he has everything he needs by way of clothes, medicine, and food. Because of this compassion and loving kindness, the man’s life is saved.

Just so, my friends, when you see someone whose words and bodily actions are not kind, and in whose heart there is nothing that can be called kindness, give rise to this thought: ‘Someone whose words and bodily actions are not kind and in whose heart is nothing that can be called kindness, is someone who is undergoing great suffering. Unless he meets a good spiritual friend, there will be no chance for him to transform and go to realms of happiness.’ Thinking like this, you will be able to open your heart with love and compassion toward that person. You will be able to put an end to your anger and help that person. Someone who is wise should practice like this.

“My friends, this is the fifth method. If there is someone whose bodily actions are kind, whose words are kind, and whose mind is also kind, if you are angry with that person and you are wise, you will know how to meditate in order to put an end to your anger.

“My friends, suppose that not far from the village there is a very beautiful lake. The water in the lake is clear and sweet, the bed of the lake is even, the banks of the lake are lush with green grass, and all around the lake, beautiful fresh trees give shade. Someone who is thirsty, suffering from heat, whose body is covered in sweat, comes to the lake, takes off his clothes, leaves them on the shore, jumps down into the water, and finds great comfort and enjoyment in drinking and bathing in the pure water. His heat, thirst, and suffering disappear immediately.

In the same way, my friends, when you see someone whose bodily actions are kind, whose words are kind, and whose mind is also kind, give your attention to all his kindness of body, speech, and mind, and do not allow anger or jealousy to overwhelm you. If you do not know how to live happily with someone who is as fresh as that, you cannot be called someone who has wisdom.

“My dear friends, I have shared with you the five ways of putting an end to anger.”

When the bhikshus heard the Venerable Shariputra’s words, they were happy to receive them and put them into practice.

Madhyama Agama 25

(Corresponds with Aghata Vinaya Sutta

[Discourse on Water as an Example], Anguttara Nikaya 5.162)

Akkosa Sutra

Insult

I have heard that on one occasion the Blessed One was staying near Rajagaha in the Bamboo Grove, the Squirrels’ Sanctuary. Then the Brahmin Akkosaka (“Insulter”) Bharadvaja heard that a Brahmin of the Bharadvaja clan had gone forth from the home life into homelessness in the presence of the Blessed One. Angered and displeased, he went to the Blessed One and, on arrival, insulted and cursed him with rude, harsh words.

When this was said, the Blessed One said to him: “What do you think, Brahmin: Do friends and colleagues, relatives and kinsmen come to you as guests?”

“Yes, Master Gautama, sometimes friends and colleagues, relatives and kinsmen come to me as guests.”

“And what do you think: Do you serve them with staple and non-staple foods and delicacies?”

“Yes, sometimes I serve them with staple and non-staple foods and delicacies.”

“And if they don’t accept them, to whom do those foods belong?”

“If they don’t accept them, Master Gautama, those foods are all mine.”

“In the same way, Brahmin, that with which you have insulted me, who is not insulting; that with which you have taunted me, who is not taunting; that with which you have berated me, who is not berating: that I don’t accept from you. It’s all yours, Brahmin. It’s all yours.

“Whoever returns insult to one who is insulting, returns taunts to one who is taunting, returns a berating to one who is berating, is said to be eating together, sharing company, with that person. But I am neither eating together nor sharing your company, Brahmin. It’s all yours. It’s all yours.”

“The king together with his court know this of Master Gautama — ‘Gautama the contemplative is an arhat’ — and yet still Master Gautama gets angry.” [1]

[The Buddha:]

“Whence is there anger for one free from anger, tamed, living in tune — one released through right knowing, calmed and Such.

“You make things worse when you flare up at someone who’s angry. Whoever doesn’t flare up at someone who’s angry wins a battle hard to win.

“You live for the good of both — your own, the other’s — when, knowing the other’s provoked, you mindfully grow calm.

“When you work the cure of both — your own, the other’s — those who think you a fool know nothing of Dhamma.”

When this was said, the Brahmin Akkosaka Bharadvaja said to the Blessed One, “Magnificent, Master Gautama! Magnificent! Just as if he were to place upright what had been overturned, were to reveal what was hidden, were to show the way to one who was lost, or were to hold up a lamp in the dark so that those with eyes could see forms, in the same way Master Gautama has — through many lines of reasoning — made the Dhamma clear. I go to the Blessed One for refuge, to the Dhamma, and to the community of monks. Let me obtain the going forth in Master Gautama’s presence, let me obtain admission.”

Then the Brahmin Akkosaka Bharadvaja received the going forth and the admission in the Blessed One’s presence. And not long after his admission — dwelling alone, secluded, heedful, ardent, and resolute — he in no long time reached and remained in the supreme goal of the holy life, for which clansmen rightly go forth from home into homelessness, knowing and realizing it for himself in the here and now. He knew: “Birth is ended, the holy life fulfilled, the task done. There is nothing further for the sake of this world.” And so Ven. Bharadvaja became another one of the Arhats.

Vitakkasanthaana Sutta

The Discursively Thinking Mind

I heard thus.

At one time the Blessed One lived in the monastery offered by Anathapindika in Jeta’s grove in Savatthi. The Blessed One addressed the Bhikkhus from there.” Bhikkhus, by the Bhikkhu developing the mind five things should be attended to from time to time. What five: The Bhikkhu attending to a certain sign if evil Demeritorious thoughts arise conductive to interest, anger and delusion, he should change that sign and attend to some other sign conductive to merit, then those signs conductive to interest, anger and delusion fade, and the mind settles and comes to a single point. Like a clever carpenter or his apprentice would get rid of a coarse peg with the help of a fine peg. In the same manner the Bhikkhu attending to a certain sign, if evil Demeritorious thoughts arise conductive to interest, anger and delusion, he should change that sign and attend to some other sign conductive to merit, then those signs conductive to interest, anger and delusion fade, the mind settles and comes to a single point.

Even when the Bhikkhu has changed the sign and attended some other sign, if evil de-meritorious thoughts arise conductive to interest, anger and delusion, the Bhikkhu should examine the dangers of those thoughts. These thoughts of mine are evil, faulty and bring unpleasant results. When the dangers of those thoughts are examined those evil de-meritorious thoughts conductive to interest, anger and delusion fade. With their fading the mind settles and comes to a single point. Like a woman, a man, a child or youth fond of adornment would loathe and would be disgusted when the carcass of a snake, dog or a human corpse was wrapped round the neck. In the same manner when the Bhikkhu has changed the sign and attended some other sign, if evil de-meritorious thoughts arise conductive to interest, anger and delusion, the Bhikkhu should examine the dangers of those thoughts. These thoughts of mine are evil, loathsome, faulty and bring unpleasant results. When the dangers of those thoughts are examined, those evil de-meritorious thoughts conductive to interest, anger and delusion fade. With their fading the mind settles and comes to a single point.

Even when the Bhikkhu has examined the dangers of those evil de-meritorious thoughts conductive to interest, anger and delusion, if those evil de-meritorious thoughts conducive to interest, anger and delusion arise, he should not attend to them. When those evil de-meritorious thoughts conductive to interest, anger and delusion are not attended, they fade. With their fading the mind settles and comes to a single point. Like a man who would not like to see forms, that come to the purview would either close his eyes or look away. In the same manner when the Bhikkhu has examined the dangers of those evil de-meritorious thoughts conductive to interest, anger and delusion, if evil de-meritorious thoughts conductive to interest, anger and delusion arise, he should not attend to them. When those evil de-meritorious thoughts conductive to interest, anger and delusion are not attended, they fade. With their fading the mind settles and comes to a single point.

Even when the Bhikkhu did not attend to those evil Demeritorious thoughts conductive to interest, anger and delusion, if these evil Demeritorious thoughts conductive to interest, anger and delusion arise, he should attend to appeasing the whole intentional thought process. When attending to appeasing the whole intentional thought process, those evil Demeritorious thoughts conductive to interest, anger and delusion fade. With their fading the mind settles and comes to a single point. Like it would occur to a man walking fast: why should I walk fast, what if I stand. Then he would stand. Standing it would occur to him: Why should I stand, what if I sit. Then he would sit. Sitting it would occur to him: Why should I sit, what if I lie. Thus abandoning the more coarse posture, would maintain the finer posture. In the same manner when attending to appeasing the whole intentional thought process, those evil de-meritorious thoughts conductive to interest, anger and delusion fade. With their fading the mind settles and comes to a single point. .

Even when attending to appeasing the whole intentional thought process, those evil Demeritorious thoughts conductive to interest, anger and delusion arise, the Bhikkhu should press the upper jaw on the lower jaw and pushing the tongue on the palate should subdue and burn out those evil Demeritorious thoughts conductive to interest, anger and delusion. Then those evil Demeritorious thoughts conductive to interest, anger and delusion fade. With their fading the mind settles and comes to a single point. Like a strong man taking a weaker one by the head or body would press him and trouble him. In the same manner the Bhikkhu should press the upper jaw on the lower jaw and pushing the tongue on the palate should subdue and burn out those evil Demeritorious thoughts conductive to interest, anger and delusion. Then those evil Demeritorious thoughts conductive to interest, anger and delusion fade. With their fading the mind settles and comes to one point.

Bhikkhus, the Bhikkhu attending to a certain sign, if evil Demeritorious thoughts conductive to interest, anger and delusion arise, he attends to another sign conductive to merit, those evil Demeritorious thoughts conductive to interest, anger and delusion fade. With their fading the mind settles and comes to one point .

When attending to the danger of those evil Demeritorious thoughts conductive to interest, anger and delusion, those evil Demeritorious thoughts conductive to interest, anger and delusion fade. With their fading the mind settles and comes to one point. When not attending to those evil Demeritorious thoughts conductive to interest, anger and delusion, those evil Demeritorious thoughts conductive to interest, anger and delusion fade. With their fading the mind settles and comes to one point: When attending to appeasing the whole intentional thought process, these evil Demeritorious thoughts conductive to interest, anger and delusion fade. With their fading the mind settles and comes to one point, The Bhikkhu pressing the lower jaw with the upper jaw and pushing the tongue on the palate would subdue and burn out those evil Demeritorious thoughts conductive to interest, anger and delusion. Then those evil Demeritorious thoughts conductive to interest, anger and delusion fade. With their fading the mind settles and comes to one point. Bhikkhus, this is called the Bhikkhu is master over thought processes. Whatever thought he wants to think, that he thinks, whatever thought he does not want to think, that he does not think He puts an end to craving , dispels the bonds and rightfully overcoming measuring makes an end of unpleasantness. .

The Blessed One said thus, and those Bhikkhus delighted in the words of the Blessed One.

NOTES

[1] The Five Ways of Putting an End to Anger, Thich Nhat Hanh. From the book Chanting from the Heart (Parallax Press, Rev.Ed., 2006)

[2] From PBS.org site, “Dealing with Anger” by Lama Surya Das