It can seem like Vajrayana’s approach to visualizing countless Buddhas and Bodhisattvas is a smorgasbord approach to Buddhism. This isn’t as terrible a metaphor as it seems. For people with different tastes, a single menu meal may not be appetizing; the smorgasbord assures that everyone has something to “eat.” The “food” in this case is spiritual understanding — the goal in Buddhism being “realizations so that we may benefit all sentient beings; to benefit all, we must appeal it must appeal to all. Why so many choices? Isn’t Buddha just Buddha?

The goal is to overcome the persistent need of beings to conceptualize and personalize. Often, in the teachings — notably in the Heart Sutra — we are taught the concept of Buddhist “emptiness.” Emptiness is not a nihilistic concept. Empty refers to “empty of concepts” or “empty of ego.” In the Heart Sutra, one translation of one of the profound paragraphs is:

“Form is emptiness; emptiness is form. Emptiness is not other than form. Form is also not other than Emptiness. Likewise, feeling, discrimination, compositional factors and consciousness are empty.”[1]

Sometimes, the word “emptiness” is qualified as “empty of inherent existence,” reflecting Buddha’s teaching on Dependent Arising and clarifying Emptiness’s meaning.

Buddha transcends mind, speech and body

Buddha is not a being; rather, “Buddha” is a state or concept. A being implies a discrete entity and ego. Buddha transcends body, speech, and mind, and therefore is not an individual (or a multiplicity of individuals.). Buddha is a state.

Since, in Mahayana Buddhist understanding, all beings have Buddha Nature — for now, temporarily obscured by concepts, obscurations, and obstacles — all beings are potentially Buddha. To help us overcome concepts, instead of the zen approach of “facing the wall,” in Vajrayana, we generate vast, unlimited conceptual mandalas — which we then break down into Emptiness. In doing this, we teach our conceptual, imaginative minds that if you remove ego and concept, we are all Oneness.

The smorgasbord of food metaphor simply illustrates that food may appear in many shapes and tastes — but it is, in essence, food. Like food, Dharma can be presented in different forms, tastes, and smells — or with every form, taste, smell and concept in the vast feast of Vajrayana buffet — all you can eat, and every taste.

His Eminence Garchen Rinpoche often uses the metaphor of ice and water. Ice in a glacier or on a mountain top, if it melts, ultimately becomes part of the vast ocean of water. When we “melt” our ego’s hold, we realize we are all One-ness.

The smorgasbord of Vajrayana — skillful means

Why did Shakyamuni Buddha teach in so many ways? Unlike some spiritual paths, with one prescribed text or scripture, there are hundreds (by some accounts, 80,000) Sutta teachings of the Buddha. Why did he teach some people that ethical conduct and virtue as the main path, while to others he taught the Bodhisattva path of compassion, and to other audiences, he taught the sometimes exotic and transcendent tantra methods (tantra just means union of method/compassion with wisdom) that appear vastly complicated?

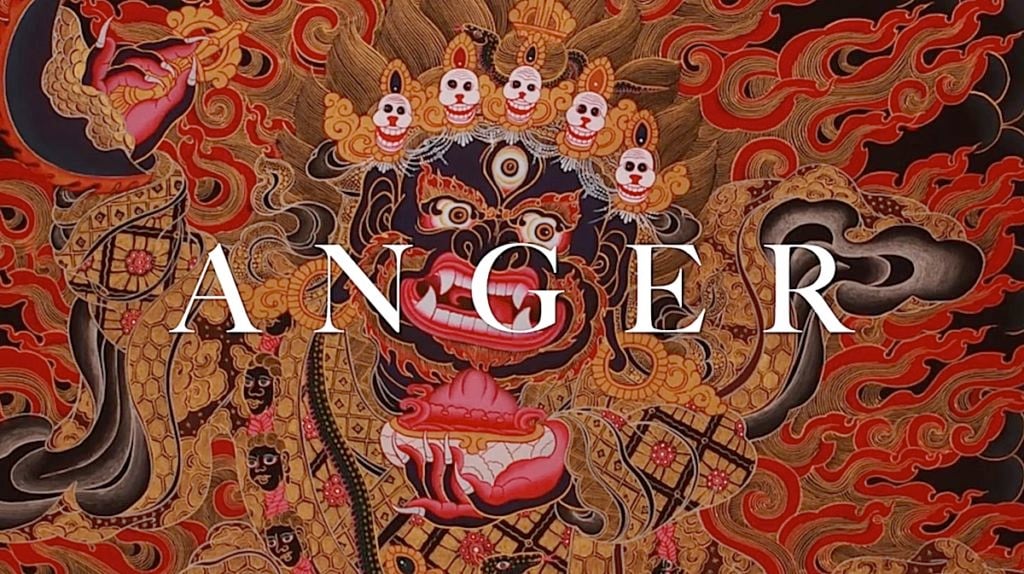

He taught differently to people of different preferences and conceptual views. The path of conduct and virtue — the ethical path of the earliest Pali Suttas — are for those who currently need to modify the negative karmic imprints of the poisons: hate or anger, jealousy, attachment and clinging.

The path of the Bodhisattva is for those ready to embrace all beings with equanimity and compassion.

The path of Vajrayana is for those whose focus should be on incorrect views and conceptualization. All paths have the same goal and focus on the teachings of the great victor, Shakyamuni Buddha — but each focuses uniquely. And, like our smorgasbord metaphor, there are more than three types of food. The nuances of Dharma teachings are as vast as the endless field of deities and mandalas. Each and every deity is not other than Buddha.

Mission focus: working on the poisons

This concept of a vast multiverse of Buddhas — literally millions of Buddhas — is expressed in the Mahayana Sutra, the Mahavairocana Sutra. In this Sutra it is explained that time and the multiverse are limitless, and that Shakyamuni Buddha was born not only on earth, to bring the Dharma, but also 1,000 times in 1,000 different universes (not just planets, but entire Universes). Long before science postulated a “multiverse” — Buddha taught experientially on the nature of limitless time and space. [4.] In this sutra, the great Vajrapani asks questions of Vairocana Buddha. This Sutra is unique; it names all the Bodhisattvas and Buddhas and gives their individual mantras. [For a feature on this sutra, with an excerpt of Chapter IV containing this treasury of mantras, see>>]

Synopsizing the 300-page Sutra is Vairochana’s concise reply to Vajrapani’s question on how he achieved Enlightenment:

“The bodhi-mind (bodhicitta) is its cause, compassion (karuṇā) is its root, and expedient means (upāya) is its culmination.”

“Expedient means, “are the focus of Vajrayana. specific methods to help us progress — to help us remove our various obscurations — we might focus on one visualized aspect of Buddha. We can synopsize these within the Five Buddha “families”

“The Five Buddhas represent the transmutation of the five delusions or poisons (ignorance, desire, aversion, jealousy and pride), into the five transcendent wisdoms (all-pervading, discriminating, mirror-like, all-accomplishing, and equanimous).” [5]

- Akshobhya and his entire family or mandala — the “immovable, changeless Buddha” — helps us overcome the disturbing emotion of anger

- Ratnasambhava and his entire family or mandala purifies pride

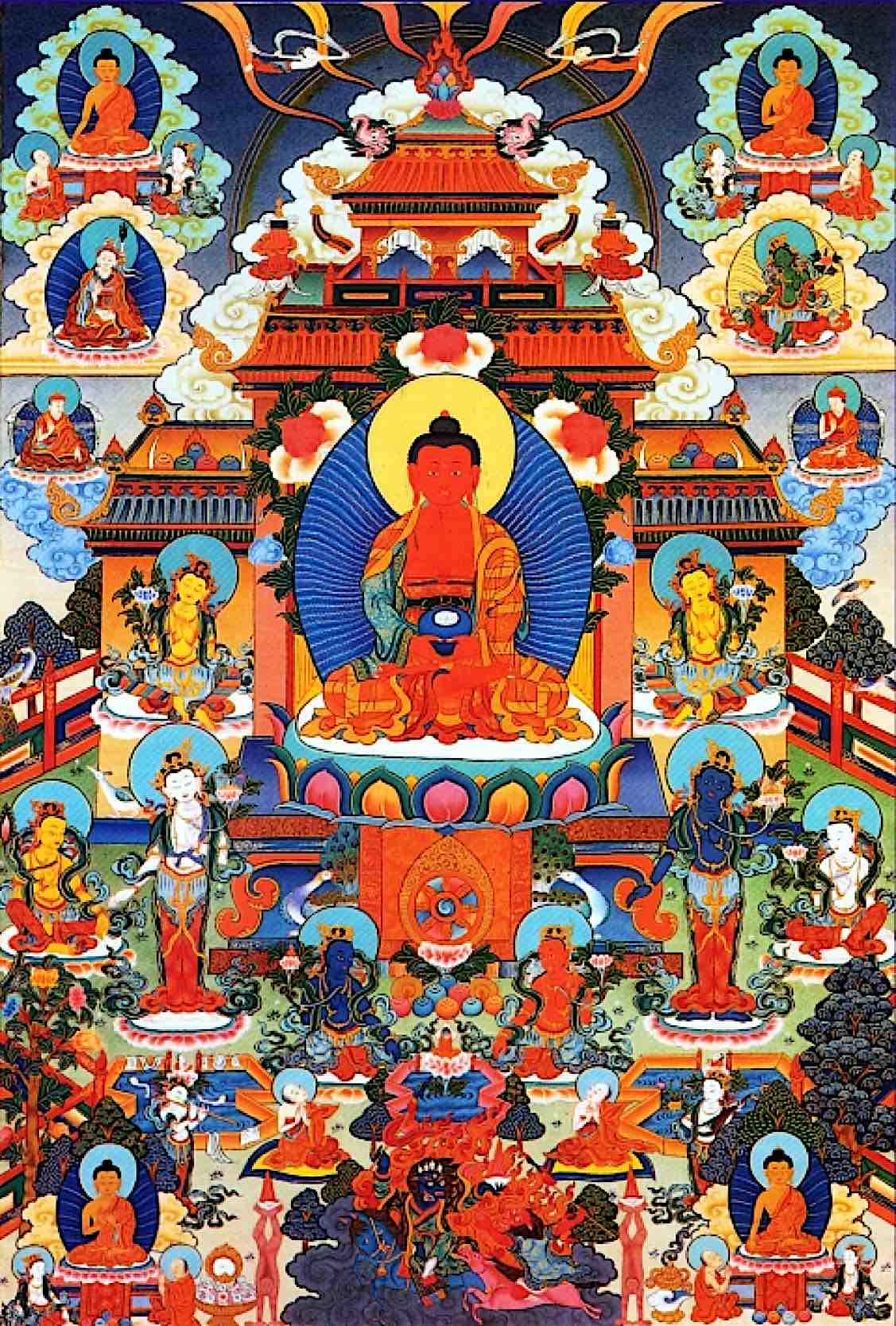

- Amitabha and his entire family or mandala purifies desire and attachments — which is fundamental to progress in Buddhist practice

- Amoghasiddhi (Amogasiddha) and his entire family or mandala (most famously, Green Tara or wrathful Vajrakilaya — both considered “activity of all the Buddhas), purifies jealousy.

- Vairochana purifies ignorance

Peaceful, wrathful, enchanting, attracting or heroic

For this reason, Chenrezig can appear peaceful and meditative and serene; and equally he can appear wrathful with multiple ferocious faces, a hundred arms; and equally in thousands of other forms. These are symbolized by the metaphor of color:

- Peaceful, and the skillful means of Buddha’s body — white, for example: Vairochana, Vajrasattva, White Tara, White Chenrezig

- Wrathful, and the skillful means of Buddha’s mind— blue or black (blue and black connote emptiness or spaciousness), for example: Vajrakilaya (blue), Yamantaka (blue), Black Mahakala (black)

- Enchanting or magnetizing and the skillful means of Buddha’s speech or Dharma — red, for example: Vajrayogini, Hayagriva, Kurukulle

- Attracting or the skillful means of Buddha’s generosity — yellow or gold, for example: Ratnasambhava, Yellow Tara, Yellow Dzambala (Jambala)

- Heroic or the skillful means of Buddha’s activities — green (which is, by tradition, the blend of all colors), for example: Amoghisiddhi Buddha or his equal and consort Green Tara

Each of these can “cross over” silnce Tara can appear peaceful and meditative and serene as White Tara; and equally as wrathful black, seductive red, golden yellow, and in countless heroic forms. Tara and Chenrezig, and all of the Buddhas are not other than One Enlightened Mind, emanating in the most suitable way to teach sentient beings.

Vajrayana Buddhism is also unique in its focus on all five (plus) senses and particularly on the error of incorrect view and illusory appearances. This, too, is the buffet, with a sumptuous feast in every color, taste, smell — all with beautiful mantras playing as we feast.

A Feast of Offerings — an Endless Field of Purelands

One of the magnificent practices of Vajrayana is the twice monthly Tsog feast, we name, and remember, and make offerings to all of the Buddhas, helping us recall the vast multiverse of Purelands. These offerings also state the “blessings” of each of the Buddha forms and their Purelands. For example, in Vajrasattva’s Pureland of Manifest Joy there is no hate. This “Feast of Offering” is both an offering and a teaching, naming each of the Buddhas, their Pureland, and their special focus.

In The Feast of Offering, a Tsog and Smoke Offering, a lengthy Sadhana describes many of the Buddhas and their particular pure lands, starting with the most famous of all, Sukhavati (The Purelands and the names of the Buddhas are not in bold in the original text, this is editorial highlighting. Sukhavati is mentioned twice because Amitayus and Amitabha are both emanations of the same being) :

“In the pure land of Sukhāvati, even the name of sorrow is unknown. It is the fortune of perfect happiness, Grant me the siddhi of long life and regard me with compassion, Amitāyus

In the pure land of Poṭala, even the names of the afflictions, the five poisons, do not exist. It is the fortune of perfect compassion. Grant me the supreme siddhi and regard me with love, Chenrezig.

In the pure land of Lotus Light, even the names of suffering and samsara do not exist. It is the fortune of the vidyādharas’ immortal life. Bestow the siddhi of the sky-faring rainbow body and grant blessings, Padmasambhava.

In the pure land of Manifest Joy, even the name of delusional hate does not exist. It is the fortune of perfect joy and bliss. Bestow the siddhi of mirror-like wisdom and grant blessings, Vajrasattva.

In the pure land Glory-Endowed, even the name of delusional pride does not exist. It is the fortune of perfect splendor. Bestow the siddhi of equanimity wisdom and grant blessings, Ratnasaṃbhava.

In the pure land of Sukhāvati, even the name of delusional desire does not exist. It is the fortune of perfect happiness. Bestow the siddhi of discriminating wisdom and grant blessings, Amitābha.

In the pure land of Fulfilled Activity, even the names of self-grasping and jealousy do not exist. It is the fortune of perfect buddha activities. Bestow the siddhi of all-accomplishing wisdom and grant blessings, Amoghasiddhi.

In the dharmadhātu sphere of Akaniṣṭha even the name of delusional ignorance does not exist. It is the fortune endowed with five perfections. Bestow the siddhi of dharmadhātu wisdom and grant blessings, Vairochana.

Bestow the fortune of the vital essences of the five great mothers – the five pure elements – and the fortune of longevity. In the emanated realm of Uddiyāna, dwell Yeshe Tsogyal and the assembly of dakinis.”

As we make meritorious offerings, we also recall all of the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas, their Siddhis and blessings and Purelands — regardless of which Yidam we focus on in daily practice. The Tsog feast is none other than a multi Pureland and mandala tour.

The Totality of Vajrayana

While Vajrayana is a total path, containing all of the other paths, including ethical and conduct, Bodhichitta and Compassion, and the universal nature of Emptiness or Shunyata. The particular focus on Vajrayana, however, is on the at the same time embracing and dissecting the true nature of “appearances” — which can include visual, audio, and other senses.

In a teaching on Vajrakilaya, Garchen Rinpoche explains why:

“It is best is one has no thought at all of self verus other or inside versus outside.”[2]

Visualization — a Major Focus of Vajrayana

One defining practice characterization of Vajrayana is visualization. Another is mantra, which is the audible form of visualization. By embracing the relative reality of countlesss Buddhas and Bodhisattvas — as many Enlightened Beings as there are cells in the body or stars in the sky — we affirm the universal Buddha nature of all sentient beings. At the same time, Vajrayana teaches, through experiential methods — rather than verbal-only teachings — that all Buddhas and Bodhisattvas are of one, Universal nature.

When, in Vajrayana, we say “all men are Chenrezig” and all women are “Tara” we are pointing to that core truth. While there are countless sentient beings, our core nature is One. We all have Buddha Nature. Until we develop realizations, though, we continue to illusory concept of individual ego. We see Chenrezig as the Bodhisattva of Compassion, and Vajrakilaya as the wrathful emanation of Vajrasattva, and Tara as the Mother of the Buddhas — while at the same time we accept the concept that all of these are of One Nature, in essence, One. Tara expresses as countless Dakinis, and as the consort of all Buddhas. Chenrezig expresses as wrathful Mahakala, Hayagriva, and countless forms. Yet, both, ultimately, are of one nature with Vajradhara or Samantabadhra, who are of one nature with Shakyamuni Buddha.

Boggling the mind is the intention?

While it can boggle the mind, that’s the intention. Ego and words are what manifest individuality. When we name a baby, he or she becomes a discrete being. Yet, that baby’s name is given to him or her, along with some preconcieved notions of conduct, ethics, language and so on — which reinforce individuality. The unfortunate side effects are the three, five or ten poisons, synopsized considely as Anger and Hatred, Attachment and Clinging (and its opposite aversion), and Incorrect View.

Ultimately, incorrect view is the source of most of the rest of the poisons. We are taught attachment and clinging and aversion by our parents. Our parents gave us a name, and taught us “I” and “me.” We discovered that crying brought us food when we were hungry, or love and kisses when we were lonely. We learned aversion when we filled our diaper or skinned our knee. We learn to be jealous when we compare ourselves to others we perceive as “them” or “you.” All of this began with the name we are given as a child — something our parents thought about for months before we’re even born. We soon learn that name even defines us. Names go in and out of fashion: which we learn in school when we are teased.

None of these concepts should be taken to mean that our parents and teachers were wrong. Without some concept of ego, and self-preservation, we wouldn’t last long in an unkind samsaric world.

What Vajrayana, however, teaches us — when we are mature enough — is that there is a way to accept both the relative “me” and “you” and the ultimate “we are all one.”

This begins with Vajrayana’s vast multiverse of mandalas of countless deities. Why so many? Because there are so many of us — all with different issues, different dominating poison views.

The Enlightened Body, Speech and Mind of Buddha emanate in every conceivable form to teach us how to focus on our particular needs.

NOTES

[1] Heart Sutra (with the full Sutta translated)>>

[2] Vajrakilaya: A Complete Guide with Experiential Instructions, His Eminence Garchen Rinpoche. Available in any bookstore, for reference, on Amazon>>

[3] From the English translation (of a very small section, “Summoning Good Fortune on page 63”) of A Rainfall of Benefit and Happiness from the Garchen Institute>>

[4] Full name of the Sutra: Mahāvairocanābhisaṃbodhivikurvitādhiṣṭhāna-vaipulyasūtrendrarāja-nāma-dharmaparyāya