There is a universal Masonic requirement of belief in Deity, which is followed by all regular Grand Lodges of the world. As Entered Apprentices, receiving Light for the first time, Masons are cautioned that no Atheist may be made a Mason. Therefore, as soon as we become Entered Apprentices, we are warned not to submit known Atheists for candidacy for the Degrees. Upon being raised to the Sublime Degree of Master Mason, Brethren are later reminded not to proffer Atheists for membership as one group in a list of people whom may never be made Masons. As Macoy puts it, “Freemasonry accepts the idea of God, as a supreme fact, and bars its gates with inflexible sternness against those who deny his existence” (p. 156).

Atheism, long the taboo of the Western World, makes up a surprisingly large percentage of the population of the United States. Nearly 30,000 Americans in 2001 identified themselves as being “Secular,” being “Atheist,” or having “No Religion” (United States Census Bureau, Table 73).

Although there is no place for Atheists in the Craft, there has been little to no reason ever given for the exclusion of such a large group of men. The following paragraphs will discuss the history of God in Masonry and give a detailed look at precedents and current trends which make the Lodge an inhospitable place for those who do not acknowledge the supremacy of Deity.

To begin, we must leave aside all Divine aspects of Masonry for a moment and focus on other core Masonic principles, namely the duties of brotherly love, relief, and truth. It becomes apparent upon brief introspection that those who disbelieve in the Grand Architect are fully capable of performing these duties. A close friend of the author’s from childhood is one of the most kind, generous, and honest people he has ever known. Indeed, he would make a good member of the Craft if he was not an Atheist. In spite of many discussions about the existence of a Supreme Being over the years, he has come to his own conclusion that there is no Supreme Being; the author therefore cannot ever recommend this man for the Degrees of Freemasonry, though he may otherwise be a good candidate. There has been little non-prejudiced, reasoned discussion explaining why this gentleman cannot be admitted—many of the arguments are clouded in rhetoric, unacceptably biased, or not argued through the use of reason. This paper will take a new look at why Masons exclude Atheists from their ranks and then explain why they should continue to do so.

Previous authors who have set out to discuss the topic of Atheism and Masonry have come to one of only a few conclusions. Either Atheists are incapable of following Moral Law and can therefore not be counted among the Craft, or Atheists, because they do not believe in God or Divine Retribution, are somehow beneath us. Both of these perspectives are outdated and prejudicial. Yet for some reason, the bulk of the literature written over the last century or more points to one or both of these perspectives.

The Morality Argument

The first conclusion is that Atheists are incapable of following God’s Moral Law, and they are therefore incapable of meeting on the Square. The most often-quoted example of this comes from James Anderson in his Constitutions of Free-Masons (p. 50): “A Maſon is oblig’d, by his Tenure, to obey the moral Law; and if he rightly underſtands the Art, he will never be a ſtupid Atheiſt, nor an irregular Libertine.” Can Atheists follow moral law? Again, from an areligious perspective, an Atheist can hold the same values that a non-Atheist holds, but for different reasons. A religious man may hold moral law to be a sacred or divine teaching, whereas a man without religion may believe that “doing good” is beneficial to himself and all of humanity, though not link it to God. Therefore, Atheists are capable of reaching the same end, that of acting uprightly, though they may have used different means to arrive at their conclusion.

If Atheists can practice brotherly love, relief, and truth, then why deny them admittance to our Order? Paton (p.154) suggests that the Atheist “… acknowledges no relation to God which should lead to fear, or hope, or love, or obedience. To him, as to the most absolute speculative atheist, the moral law is nothing.” Paton suggests that following moral law is but a whim, a fleet of fancy which may be turned upon because a man who does not fear God has no reason to remain moral. Perhaps the best example of this philosophy was given by Albert Pike (ch. 23):

The intellect of the Atheist would find matter everywhere; but no Causing and Providing Mind: his moral sense would find no Equitable Will, no Beauty of Moral Excellence, no Conscience enacting justice into the unchanging law of right, no spiritual Order or spiritual Providence, but only material Fate and Chance. His affections would find only finite things to love; and to them the dead who were loved and who died yesterday, are like the rainbow that yesterday evening lived a moment and then passed away. His soul, flying through the vast Inane, and feeling the darkness with its wings, seeking the Soul of all, which at once is Reason, Conscience, and the Heart of all that is, would find no God, but a universe all disorder; no Infinite, no Reason, no Conscience, no Heart, no Soul of things; nothing to reverence, to esteem, to love, to worship, to trust in; but only an Ugly Force, alien and foreign to us, that strikes down those we love, and makes us mere worms on the hot sand of the world. No voice would speak from the Earth to comfort him.

Paton adds the idea that Masons believe in a “Future State,” which he defines loosely as rewards and punishments to be given in the next life or in the afterlife. In this case, Paton makes the point that without a belief in a Supreme Being or the afterlife, there is no immortal consequence to breaking moral law. This has historically been a key reason for denying Atheists positions in Masonry—they cannot be trusted to maintain morality. Although it is true that Atheists have no belief in immortal consequences, good men tend to be good men; using this as the only argument to keep Atheists out of Masonry is hardly sufficient.

The other perspective often repeated in Masonic literature dealing with the subject of Atheists is that those who do not believe in a Grand Architect are somehow baser than those of us who do believe. The effect of allowing Atheists entry into Masonry

would be to lessen confidence and weaken friendship, and no obligation would be regarded as binding among men … Mankind would give way to the most unrestrained, cruel, and base passions of their worst natures. The very foundations of good order would be subverted, and society would soon degenerate into a state of anarchy. (Ernst, p. 69-70)

This is an even more prejudiced view than the view that Atheists cannot be trusted to uphold moral law, though there are connections between them. Anderson’s reference to Atheists as “stupid” (meaning base, not of lower intelligence), implies the belief that non-believers are less of men. This, in addition to the aforementioned arguments, makes up the bulk of the arguments opposing the Atheist’s admission to the Lodge.

From the Historical Perspective

In the time since most of the above-cited works were written, we as a secular, Western society have moved beyond the name-calling and prejudices that plagued our forefathers. Indeed, the forbearers of our Craft did not always require religion in their ritual. Prior to the establishment of modern Freemasonry, when our predecessors still hewed stone and built magnificent cathedrals, religion may not have always played a part in meetings.

There is no denying that Masons as early as c.1430 were required to be Christian. Surviving fifteenth century records indicate that there were religious overtones in Masonry this early as c.1430, when the document now known as the Regius MS was written (Waite, p. 3-4). And though there was a requirement that Masons at this time “lift up their hearts to Christ” (Waite, p. 4), it was not until three centuries later that there was an absolute requirement that Christianity had to be professed (Coil, p. 515). Early on, therefore, it was certainly preferred that members of the Craft be Christian and God-fearing.

From a historical standpoint, however, how much was the Christian requirement simply based on the power and control exercised by the Church during the late Middle Ages? Given the nature of European feudal society, especially on the British Isles and in France, Church officials held most power in most places, and they held in their hands the “only” way to worship. In the Regius MS, Masons were required to “assist at Holy Mass with becoming reverence.” Since the primary buildings constructed by stone masons at the time were cathedrals, or places of Christian worship, there was likely some degree of religious oversight of the process by a Church official. Though they may not have been given the operative secrets of the guild (therefore making the Catholic Church distrust the Masons as an organization in later centuries), it is not an unreasonable assumption that the edicts requiring Christian faith may have come—either directly or indirectly—from the clergy.

Indeed, in the era of the Masonic Guild, it is clear historically that there was often a blurring of lines between Church and Lodge. The Comacine order, the early forbearer of later guilds of masonry, for example, was known to admit priests as members.

Masonic Monks were not uncommon, and there were such monks associated with the Comacine body; so that qualified architects were easily found in the ranks of religious orders. (Scott, p. 160)

Belief in God has clearly been at the core of Masonry since its inception. Given the obvious historic influence of the Church on what was to become Speculative Freemasonry, ritual and belief system within the Lodge was “erected to God.” No room for Atheists was left; this was likely done on purpose, at least early on, through the influence of the monk-architects. This, however, was likely not a sinister act. After all, “A Freemason in the year 1200 A.D. … thought of himself as a Catholic, [but] it did not occur to him to think of his art or craft as having anything to do with Catholicism” (Haywood, p. 122). Nonetheless, the required belief in Deity became a core tenet of the fledgling guild during that era.

Beyond the Historical Perspective

Until this point, this paper has dealt with Masonry from a historical perspective. Various opinions of prominent Masonic authors from the last three centuries were discussed, and a brief history of the inclusion of God as a part of Masonic teaching has been laid out. However, none of the theory or philosophy thus far presented has gotten to the heart of the issue: why can’t Atheists be admitted to Lodges today? Answers of “that’s the way it has always been” have been proffered (see, for example, Lippincott & Johnson, p. 84). However, this excuse is on its surface weak. There was a time when only men of sound body were admitted; several Grand Lodges, including the Grand Lodge of the District of Columbia, have begun admitting men with physical deformities (see, for example, Hoenes, p. 6-7). Other changes have been made over time; admitting Atheists would only be a modernizing adaptation. Other answers to this question have been dealt with above. Though some may find solace in these answers, others may find them to be excuses based on prejudice and fear. The remainder of this paper will attempt to discuss, why, in the culturally accepting 21st century, there is still no room for Atheists in Masonry.

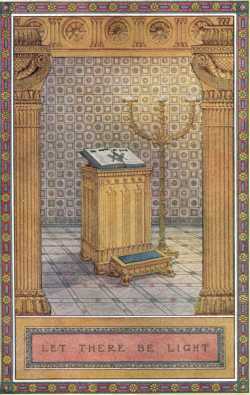

In the end, the origins of religiosity in Masonry are not as important today to the argument of admitting Atheists as the role of the Mystic Tye. The prime reason for continuing to deny Atheists admittance into our Brotherhood is the presence of God and religion throughout Masonic beliefs, as noted before. By itself, the ritual we practice has overtones of the Grand Architect. These rituals would make Atheists (a) uncomfortable given their individual beliefs and (b) unable to understand the nuances of Masonry, given the absolute importance Masons put on their faith to God. Beyond ritual, the myths and legends that make Masonry what it is today are inherently religious.

Was Freemasonry only a society of fraternity, with no religious component, such as a Moose Club, or a charity-only organization, such as Rotary International, these stringent requirements regarding an individual’s beliefs would not be as important. Our Fraternity, however, is one with religious components. One needs look no further than the Ritual presented to a Candidate during the First Degree. A candidate is asked in whom he puts his trust and is required to give an answer which acknowledges a belief in Deity. He is told that since his trust is in God, he is sound in faith in the Great Architect. In other words, to proceed past the first moments in the Lodge, one must affirm his faith in Deity.

Naturally, such a display would be difficult for someone who does not hold a belief in the Supreme Architect of the Universe. One might assume that an Atheist, not being tied to his morality, would lie (as has been suggested by some); but to what end? What would an Atheist see in an open lodge that would interest him?

As the ritual stands, an incredible number of references are made to the Volume of Sacred Law, to God, and of our submission to Him. An Atheist in such surroundings would likely feel uncomfortable.

Nor should we change our Craft and the beliefs of our Order; to do so would be to destroy the heart and soul of the Fraternity. The foundation of Masonry, that which supports us and holds us together, is the shared belief in the existence of Deity:

Other foundation there is none; upon God Masonry builds its temple of Brotherly Love, Relief, and Truth … God is the first Fact and the final Reality—the Truth that makes all other truth true; the corner stone of faith, the keystone of thought, the capstone of home … Everything in Masonry has reference to God, implies God, speaks of God, points and leads to God. Not a degree, not a symbol, not an obligation, not a lecture, not a charge but finds its meaning and derives its beauty from God, the Great Architect, in whose Temple all Masons are workmen. (Newton, p. 58-60)

In reality, therefore, Masonry is necessarily theistic. There is no part of Masonry which does not call upon the Great Architect, in whose presence we conduct our meetings.

If an Atheist were to join the Craft, he would find that he would be not be able to fully understand even part of the esoteric mysteries which bind Masons together. Looking no farther than the lecture and charge given to new brethren upon being initiated into our Craft, it is clear that the firm belief in God is required to understand the nuances of these lessons.[ii] Take, for example, the significance of something as simple as the white leather apron: as an “emblem of innocence,” the white leather apron’s purpose is to symbolize right and proper behavior is the path to the Celestial Temple above (Grand Lodge of the District of Columbia [hereafter GLDC], p. 179-180). Furthermore, the significance of Jacob’s Ladder, key instruments thereof being Faith, Hope, and Charity, shows that proper reverence must be given to Deity. Finally, an Atheist would likely be put off by the discussion of the perfect Ashlar and Trestle Board:

By the rough Ashlar we are reminded of our rude and imperfect state by nature; by the perfect ashlar, of that state of perfection at which we hope to arrive by a virtuous education, our own endeavors and the blessing of God; and by the Trestle Board we are also reminded that as the operative workman erects his temporal building agreeably to the rules and designs laid down by the Master on his Trestle Board, so should we, both operative and speculative, endeavor to erect our spiritual building in accordance with the rules laid down by the Supreme Architect of the Universe in the Great Books of nature and revelation, which are our spiritual, moral and Masonic Trestle Board. (p. 183)

What does it mean to “erect our spiritual building in accordance with the rules laid down by the Supreme Architect”? One interpretation is that our “spiritual buildings” are our individual souls—the essential parts of ourselves, which will inevitably be brought to the World Hereafter (what Paton called the “Future State”). We therefore instruct our new initiates to stand tall before God, marking our lives against those laws He has set down for us, in our Volumes of Sacred Law and in our hearts as Brothers formed in His image. To “erect” our souls is to stand upright and to act nobly in our lives, especially in service to Deity.

It is therefore impossible to allow Atheists to join order because they are incapable of measuring themselves against the will of God, to whom Masons all must show reverence. Though an Atheist may be a good man in the traditional sense of the word, as someone who acts nobly and charitably towards his fellow man, he is missing a vital component of Masonry: reverence to God. It is only through God that a man may be a Mason, for it is only through appropriate “reverential awe which is due from a creature to his Creator” (GLDC, p. 187) that a man can be an appropriate candidate.

Bibliography

Anderson,

J. (1723) The Constitutions of the

Free-Masons: Containing the History, Charges, Regulations, &c. of that most

Ancient and Right Worshipful Fraternity.

London: William Hunter.

Coil,

H. W. (1961). “Religion” in Coil’s

Masonic Encyclopedia. New York:

Macoy’s Masonic Publishing & Masonic Supply Co., Inc.

Ernst,

J. (1870). The

Philosophy of Freemasonry; or, an Illustration of Its Speculative Features,

Based upon the “Interrogatories” and the “Ancient Charges” of the

Institution. Cincinnati: Jacob

Ernst & Co.

Grand

Lodge of the District of Columbia (GLDC). (2003). Masonic

Cipher, 3rd ed. Washington,

DC: Grand Lodge of the District of Columbia.

Haywood,

H. L. (1948). The

Newly-Made Mason: What He and Every Mason Should Know About Masonry.

Chicago: The Masonic History Company.

Hoenes,

W. R. (Spring, 2007). “Honoring

Service and Sacrifice” in The Voice of

Freemasonry. Vol. 24, No. 2.

Hunter,

F. M. (1975). A

Study and an Interpretation of The Regius Manuscript: The Earliest Masonic

Document. Portland, OR:

Research Lodge of Oregon No. 198 AF&AM

Hutchinson,

R. R. (2006). A

Bridge to Light: A Study in Masonic Ritual & Philosophy, 3rd

ed. Washington, DC: Supreme

Council, 33˚

Lippincott,

C.S., Johnston, E. R., eds. (1926). Masonry

Defined: A Liberal Masonic Education, 15th ed.

Memphis, TN: Masonic Supply Co.

Lomas,

R. (2006). The

Secrets of Freemasonry: Revealing the Suppressed Tradition.

Selected and Revised Edition. London:

Magpie Books.

Macoy,

R. (2000). A

Dictionary of Freemasonry, 2000 ed. New

York: Gramercy Books.

Newton,

J. F. (1927). The

Religion of Masonry: An Interpretation.

Washington, DC: The Masonic Service Association of the United States.

Paton,

C. I. (1878). Freemasonry:

Its Two Great Doctrines, The Existence of God and A Future State.

London: Reeves and Turner.

Pike,

A. (1871). Morals

and Dogma. Accessed via <

http://reactor-core.org/morals-and-dogma.html> on 16 August 2007.

Scott, L. (1899). Cathedral Builders.

London: Sampson Low & Co.

United

States Census Bureau (2007). The

2007 Statistical Abstract. Accessed

via <http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab> on 15 August 2007.

Waite,

A. E. (1925). Emblematic

Freemasonry: and the Evolution of its Deeper Issues.

London: William Rider & Son, Ltd.

Notes

[i] Special thanks go to Joan Sansbury and Larissa Watkins at the Library of the Supreme Council, 33˚, Washington, DC. Without their assistance, I would not have had access to so many materials and so much Masonic information.

[ii] All references to the lecture and charge of the 1˚ are taken from the non-secret (i.e. not ciphered) work of the Grand Lodge of the District of Columbia [GLDC].