There is no debate that Bodhidharma is an inspiring and towering presence in Mahayana Buddhism and the mystery of Shaolin. The life of the legendary monk Bodhidharma does have many facets that are subject to debate; based on truth, perhaps, but not necessarily literally provable. Not on the list of “debatable” would be the fact that he existed or his contribution to Buddhism.

By Dave Lang

He is said to be one of the founders of Zen, and Ch’an Buddhism. He is mysterious, iconic, and powerful. Some accounts recall him as rather ill-tempered, although this was likely in classical Zenmaster style, as a skillful means. There is no debating that he was abrupt with politicians and kings. He is, perhaps for this reason, often portrayed in statues and paintings with fierce, penetrating eyes. [To see the our feature on Bodhidharma, mentioning his snappy interchange with Emperor Wu of Ryo of China, see>>]

Bodhidharma image from Truc Lam Buddhist Temple in Dalat Vietnam. He is s towering presence in Chan and Zen Buddhism, a historical monk with many legendary stories, who influenced Shaolin and Kungfu.

In this Buddha Weekly feature, we do our best to explore the somewhat legendary history that surrounds the monk and his life’s work. Like many legends — and more than some — his life story is inspired by a living, historical person. Today, people even take also undertake pilgrimages to honor the one he made: the journey that would ultimately serve as the beginning of his legacy.

Where Was Bodhidharma From?

When he existed and where he is from are 2 of the biggest sources of debate in regards to Bodhidharma. There are accounts that recall him as being from Persia circa 547 CE. Other accounts place him as a prince from Kancheepuram, which is in modern-day India (There is a Bodhidharma temple in Kancheepuram.) Other accounts of his early years would support this claim.

A relief at Shaolin monastery illustrating the legend of Hui Ke and Bodhidharma.

Early Years

There aren’t many sources that offer much information about the early years of Bodhidharma, however one account would support the claim that he was from India. According to this teaching, it was around the year 495 AD when an Indian prince named Bodhidharma was nearly assassinated by his brothers in an attempt to secure the throne of their sick father, the King. It is said that the karma of Bodhidharma was good enough to help him survive the attacks. Although he was the favourite son of the king, he had no interest in power or politics and rather chose the life of a Buddhist Monk, studying under the famous master Prajnatara, who was likely a woman.

Prajanatara was an emanation fo the Bodhisattva Mahasthamaprapta (Chinese painting). There is evidence that Prajnatara was a woman. Prajnatara was the 27th “patriarch” of Indian Buddhism.

Prajñātārā, also known as Keyura, Prajnadhara, or Hannyatara, was the twenty-seventh patriarch of Indian Buddhism according to Chan Buddhism — and the teacher of Bodhidharma. Prajnatara according to evidence was a woman.

From a feature in Tricycle: “Prajnatara was the teacher of Bodhidharma, the founder of the Zen school. In addition to the notable role of being Bodhidharma’s teacher, Prajnatara is also an interesting figure because there is some evidence that she was a woman.” [4]

A statue and background celebrating the 5th-6th century monk Bodhidharma undertaking his great journey from India to China. This is a scene in An Hao Vietnam in the Van Linh Buddhist Pagoda. Notice the fierce, penetrating eyes.

The Journey to Zhen Dan

Bodhidharma’s name is, to many, synonymous with the famous Shaolin temple. This was founded by a monk named Ba Tuo — a monk who had also migrated to Zhen Dan, the country known now as China. Ba Tuo had been granted land at the base of the Shaoshi mountain by the emperor at the time — Shao Wen; This is the land where the Shaolin temple and all of the teachings that would come out of it were to be. Of course, Zhen Dan, China, is very far from Kancheepuram — in the modern-day state of Tamil, India.

Back in Kancheepuram, a young Bodhidharma was insecure. He knew his master, Prajnatara’s time would come, and didn’t know what he would do on the master’s passing. So he asked her (most evidence seems to indicate Prajnatara was female.) Prajnatara told him that he must travel to Zhen Dan, which upon the death of Prajnatara he would do so, though this journey not be without conflict for Bodhidharma.

The great monk Bodhidharma brought Chan Zen teachings to China from India and influenced the Shaolin Temple and martial arts. His journey from India was eventful and legendary.

Prajnatara wasn’t the only figurehead in Bodhidharma’s life whose time had come. Upon the passing of his father, one of the young monk’s brothers had become the King and subsequently passed the throne on to his kin. This nephew of Bodhidharma sought to make reparations for the suffering that had been inflicted upon his uncle Bodhidharma by his father and other uncles and asked Bodhidharma to stay nearby.

The Shaolin temple ZuTing shown here in recent times, was founded in 495 and was, famously, where Bodhidharma came to teach.

There, under his rule, the nephew could care for and protect him, but Bodhidharma knew that he must fulfill his master’s wishes and travel to Zhen Dan. The king resigned to this choice and ordered that carrier pigeons be flown in advance with a message asking them to care for Bodhidharma. Thus, his arrival created something of a stir among the Chinese people and he became famous.

The Scorn of an Emporer: The Crossing of the Yangzi River

When it comes to the legend of Bodhidharma, there are many stories that take place. Many have, as legends tend to, a degree of the superfluous – though often in support of a valuable lesson or Buddhist principle. When it comes to objective history, there is little but the lore of the land through which he traveled, though there are some threads to his story that remain more or less common through most recollections.

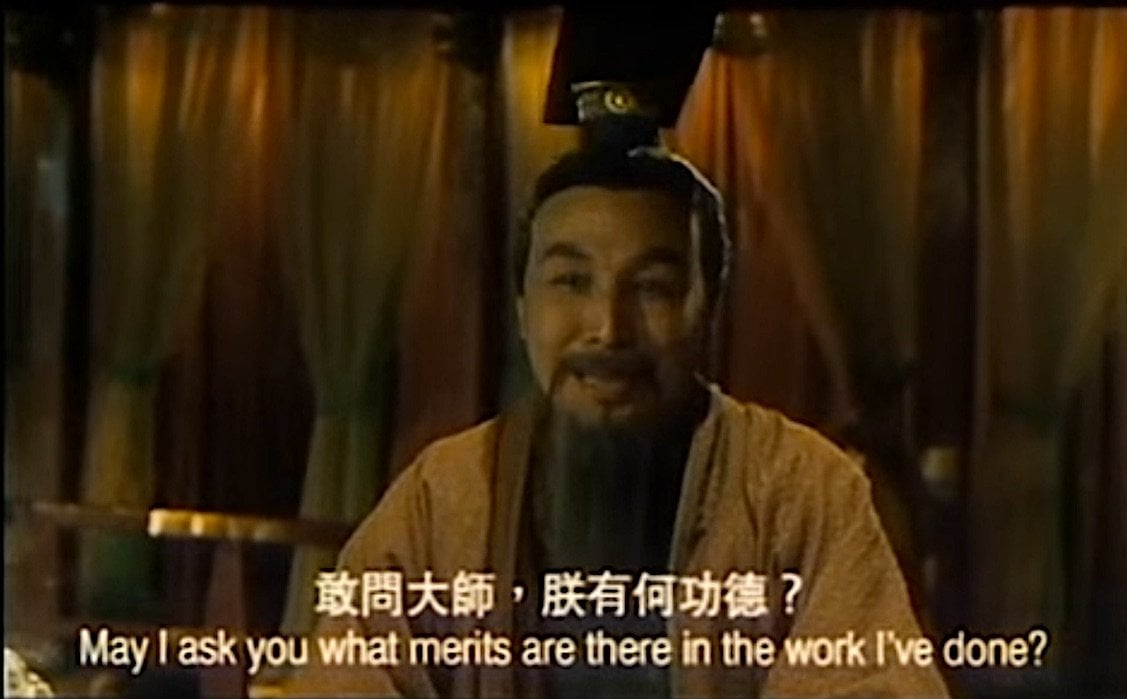

When the Emperor of China asked Bodhidharma if his Dharma work had earned him any special merit, the sage answered “None Whatsoever.” From the movie Bodhidharma.

Around the year 527 AD (an estimate and subject of debate), he crossed into China through Guangdong. He was known not as Bodhidharma by the locals, but as Da Mo. Many of the people who had heard of or received the message that Bodhidharma was coming wished to greet him and were excited to hear his teachings. However, the Mahayana Buddhist monk, when greeted by a large crowd did not speak but rather meditated. This garnered quite the reaction from the crowd – the entire spectrum of emotions was present throughout the people.

This caused quite the stir and only served to further his fame to the point where Emporer Wu Ti was aware of the monk known as Da Mo. This was right around the time when Buddhism was making a splash in the otherwise Confucian kingdoms of China. Though much of China wasn’t friendly to Buddhism, Emporer Wu was enthusiastic and had many Buddhist statues built and funded many Buddhist temples as well. So he was excited to meet Da Mo and learn more of his wisdom and the pursuit of Nirvana.

Bodhidharma however, on meeting the gleeful ruler, assessed that his reasons for seeking wisdom weren’t pure. The emperor sought compliments and praise and intended to have the then Sanskrit teachings translated and given freely to the masses. Da Mo realized that all of this desire, though wrapped in the teachings of Buddhism, was ultimately to be a source of suffering. He told Wu Ti what he observed, which was news that the ruler did not take well: He banished Da Mo from his palace, so the journey for Bodhidharma continued North.

The Dharma cave at Shaolin temple, a famous historic site at Denfeng Henan China. Some say that he meditated for 9 years, with Dazu Huike waiting outside the cave for the entirety of that period.

The legendary journey: crossing the river on reeds

Along this route many legends were born, including that of his meeting of Shénguāng (神光, Wade–Giles: Shen-kuang; Japanese: Shinko) — a military general turned monk who was speaking to a crowd. (His monastic name is best known as Dazu Huike, his secular name was Shénguāng.)

Da Mo appeared in the crowd, highly noticeably thanks to his foreign features. As Sheng Guang would speak, Da Mo would nod or shake his head in approval or disagreement. The ex-general became enraged and struck out Da Mo’s two front teeth.

Rather than being met with a fight, he was surprised when Da Mo smiled and walked away. Huike followed the monk to the side of the Yangzi River, where a woman had a large bundle of reeds. Da Mo asks for a reed, which the old woman grants him and is said to float across the river on the reed and his chi alone. Huike (Shenguang), however, grabbed a handful without asking and attempted to follow Da Mo — only to fall into the river and nearly drown.

The woman informed Huike that because he didn’t ask, he had disrespected himself, and further, that the man he had been following was his master. As she took mercy on Huike, the reeds began to float again, and brought him too, safely to the other side of the river.

Bodhidharma is also the legendary founder of Kungfu in Shaolin, a method of both exercises for monks and self-defense as well a discipline and focus. Today, Shaolin is world-famous and demonstrates kungfu around the world This demonstration is at the Shaolin temple.

Bodhidharma, Ch’an, and the Temple of Shao Lin

While most accounts agree that Da Mo or Bodhidharma did make it to the temple of Shao Lin (Shaolin), how the monks greeted him is a subject of contention. By some accounts, he was greeted and chose to meditate in a cave on the mountain beneath which the temple stood. Others say that he was initially refused entry, and as such meditated in the cave. What is agreed upon, is that he reached the Shao Lin temple and meditated for a very long time. Some say that he meditated for 9 years, with Dazu Huike waiting outside the cave for the entirety of that period.

Huike cuts off his arm

After this, the monks built a room for Da Mo, where he would meditate for another 4 years with Dazu Huike (487–593;[Chinese: 大祖慧可; pinyin: Dàzǔ Huìkě; Wade–Giles: Ta-tsu Hui-k’o) outside his door. Finally, after years without significant teachings, Dazu Huike couldn’t wait for another second and woke Da Mo from his meditation.

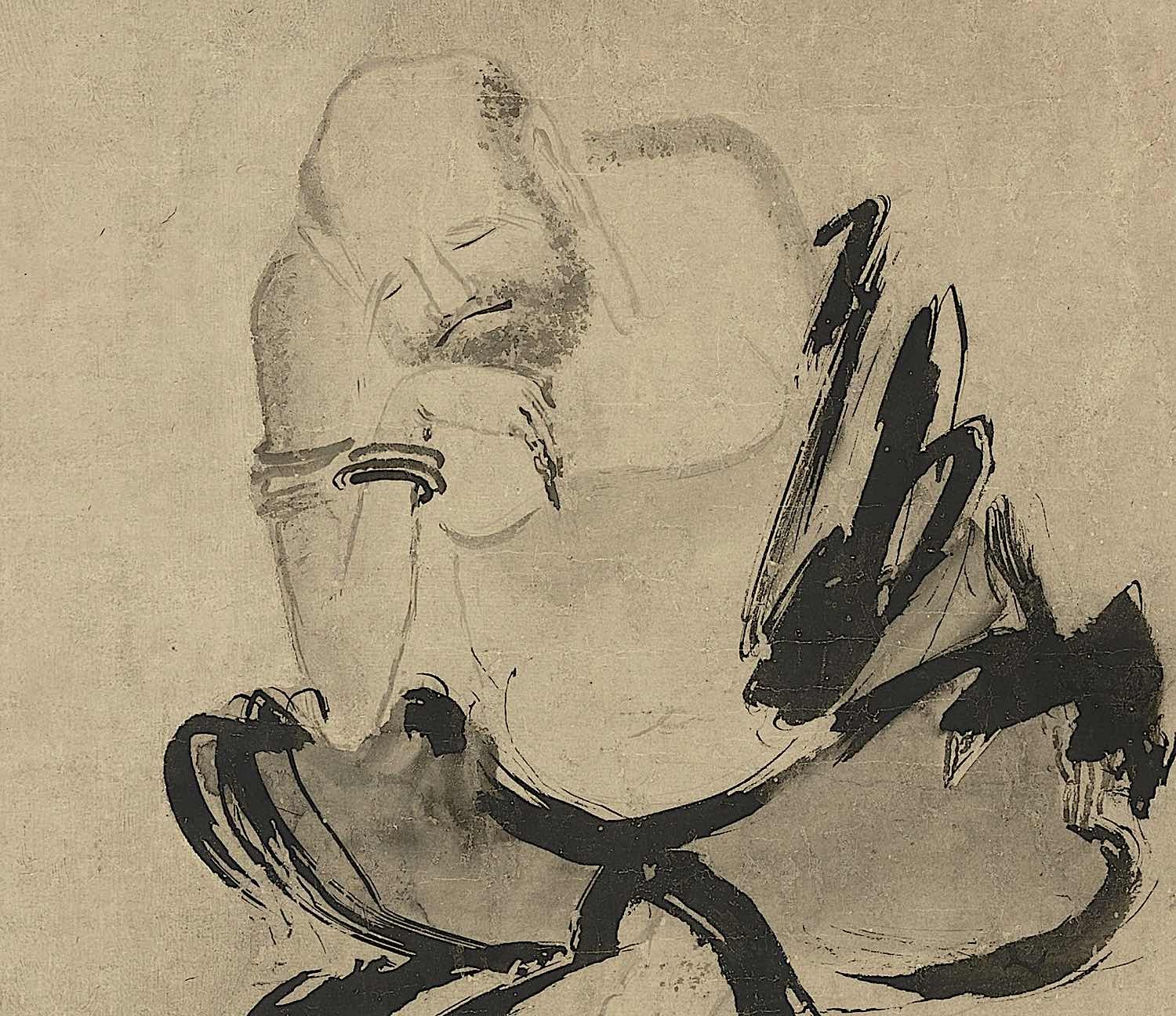

Dazu Huike thinking in a painting from the 10th Century (Northern Song, 5 Dynasties period) by Shik Ke. Notice he has one arm. He cut off his arm himself to show his sincerity as a repentant student of Bodhidharma.

When Da Mo again refused to teach him, he cut off his left arm. On seeing this, Bodhidharma decided that he would teach Huike, and to this day, Buddhist monks at the Shao Lin temple only greet each other with their right hand, out of respect.

Dazu Huike would go on to become the Abbott of the Shao Lin temple. Bodhidharma taught him, and also the monks who would become famous for their fighting skills. He helped to train and meditate as well, and his teachings of Mahayana Buddhism would form the basis of Ch’an, or as it is better known by its Japanese name, Zen Buddhism.

While many details are subject to debate, the main elements that hold true make Bodhidharma an important and highly revered figure in the world of Buddhism.

Sources

[1] https://usashaolintemple.org/chanbuddhism-history/

[2] https://depts.washington.edu/triolive/quest/2007/TTQ07031/history/founders/bodhidharma.html#:~:text=There%20are%20many%20legends%20about,crept%20close%20by%20the%20cave.

[3] https://www.learnreligions.com/buddhism-in-china-the-first-thousand-years-450147

[4] https://www.britannica.com/topic/Mahayana

[5] Tricycle feature by Jeffrey Arnold on Prjanatara>>