When Buddha decided to find a solution to suffering in our universe, one of his first acts was to cut his hair. When a novice renounces Samsaric life to become a renunciate, the symbolic representation of that mission is cutting the hair.

Ultimately, if you distill the Buddhist path down to one concept, it would be: “to cut the poisons of samsara.” Cut, cut, cut. This cutting activity winds its way through all the teachings and methods of all Buddhist traditions.

NOTE: No, this isn’t a feature about haircuts. Our eleven-part feature, starting with this introduction “Buddha Didn’t Teach That?” focuses on the core method of Buddhism — regardless of tradition or school — to cut the ten poisons of Samsara.

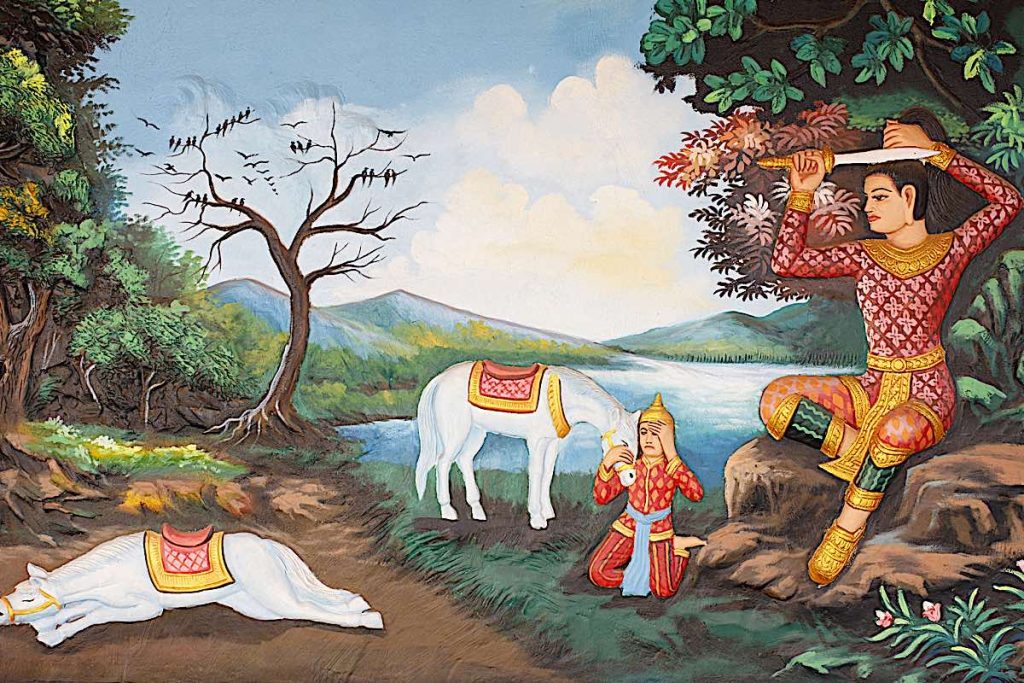

Buddha cuts his hair as a symbolic act of “cutting” samsara. With this act, he starts his heroic journey toward ultimate Enlightenment, for the benefit of all sentient beings. Image from Preah Prom Rath Monastery Cambodia.

Buddhism is not a path of rigid dogma. In fact, Buddha taught a “self-help” path. In Samyutta Nikaya v. 353, he is recorded as saying:

“Take it upon yourselves to lead the way.”

Whether or not these were his exact words really doesn’t matter. Ultimately, we are “lamps unto ourselves.” What the Suttas and Sutras and Tantras do contain — all of them, not some of them — are diverse methods within true Buddha Dharma to accomplish a singular mission. To: cut, cut, cut, cut, cut, cut, cut, cut, cut, cut. Ten cuts, to be precise.

Buddhism is, at its heart, a spiritual path focused on “cutting.” Cutting unwholesome activities. Cutting the ten poisons of Samsara. Cutting our addictive attachments. Cutting our hatred. All Buddhist practices can be reduced to “cutting” — cutting our ordinary perceptions of reality, cutting our anger, cutting our hate, cutting our greed. Cut, Cut, Cut! (In Sanskrit, Phet, Phet, Phet!)

Following Buddha’s example, fully renounced monks cut their hair. This is part of an ordination ceremony in Thailand.

“Buddha didn’t teach that!”

What inspired this eleven-part series was a humble (and well-meaning) comment on one of our social media channels — “Buddha didn’t teach that!”

Although the commenter’s heart was in the right place, it came from a place of innocent attachment — one of the poisons. Being attached to a belief in one method, taught by Buddha — one and no other — is itself a symptom of the klesha of attachment.

Which of the 84000 recorded teachings of Buddha are the “right ones”? Which image of Buddha is the right one? Which color? Which language? Buddha taught many skillful means as remedies for the same afflictions. One core truth winds its way through all Buddhist traditions, regardless of diverse views, appearances, and teaching methods.

None of us can actually quote the Buddha. That’s impossible. Even if we cite the oldest Suttas recorded, they were written down from an oral tradition over hundreds of years. The original “basket of teachings” was recorded in 29 BCE — 454 years after Buddha’s Paranirvana.

Yes, we can rely on the truths recorded in all Sutta, Sutra and Tantra, passed down over centuries, but that’s not the same as saying these are Buddha’s actual words. We can only cite truths — core truths and skillful methods. What are these core truths? If we are to distill it down to a central mission it is simply to “cut the poisons.” Cut, cut, cut.

The “Sanctuary of Truth” in Pattaya Thailand. All Buddhist traditions, regardless of presentation, contain core truths. That there is suffering. That we can remove suffering with the noble Eightfold Path. All methods that stem from the core teachings are methods — and all are equally correct, regardless of diversity.

Does it matter if the original basket of teachings written nearly five centuries after Buddha’s death were more “correct” words than the later Mahayana Sutras? (Or vice versa?) Ultimately, no. Not if we’re concerned with accomplishing the goal of “cutting the poisons.” Whichever method works for one student, might not work for another. And, dwelling on the method is a form of attachment, too.

For this reason, this eleven-part series is not a series about which teachings of Buddha are correct. The comment was just the inspiration for a quick comparison of how all the various traditions — all of them correct and valuable paths — focus on different methods to “cut” the poisons. Cut, cut, cut!

Buddha cuts his hair as a symbolic act as he heroic ventures out from his sheltered life to solve the suffering of all beings.

Buddhisms Ten Poisons — the ten Kleshas of and their antidotes

The remedy to the ten poisons, in whatever form, are the Practical and Crucial Teachings of Buddha. Above all Buddhism is a practical path.

It may surprise Buddhists and non-Buddhists alike to claim that Buddhism is actually the most pragmatic and practical of spiritual paths. Yes, it’s easy to get lost in exotic Yidams and deities, secret practices and empowerments, powerful mantras and rituals. Watching a complex Tibetan Buddhist Puja at a Buddhist temple makes the practices seem rigid and complicated. Or, a short visit to a Zen or Chan temple may convince us they just do nothing but sit. All the bowing and prostrating and prayers and chants — and thousand-armed deities — make it seem like the most exotic of paths.

This outer, cursory glance at Buddhist practice is not only misleading, it would be enough to send many non-Buddhists running.

Which of these many faces are the true aspect of Wisdom and Compassion. All are the same. All represent aspects. All represent core truth. Top right ferocious Yamantaka (two arms), top centre Yamantaka with nine heads — Manjushri’s head on top — top right a rarer tantric form, center bottom Orange Manjushri with Wisdom Sword, bottom right center Peaceful Black Manjushri, bottom Right Wrathful Black Manjushri and bottom left, the syllable Hum on a Lotus.

All forms of Buddhism are about “cutting”

When we step aside, looking at these methods for what they are — antidotes to the ten poisons of our life — we grasp the purpose of all the ritual, chanting, and the symbolism of monstrous visualizations of wrathful Buddhas.

What are we cutting?

What are these manifold methods taught by Buddha designed to do? At their heart. every single teaching and method in Buddhism — from the first teaching of Buddha in Deer Park to the most exotic of rituals — are about “cutting.”

Ordination ceremony of Thai Buddhist monks after cutting their hair. The act of ordination is a “cutting” activity, renouncing Samsara as the path to ultimate realizations. Ordained monks cut everything at once. Lay practitioners might cut one thing at a time, or use unique methods of practice. All methods are designed to cut the ten poisons — different to suit different minds.

The so-called 84,000 Teachings of Buddha, which include everything from the original Pali Suttas to the most secret of Tantras, are all about: cut, cut, cut.

At one level, it’s that simple. Of course, the secret sauce is not the mission of “cutting” but the various methods Buddha taught for overcoming our many poisons (sans. kleshas):

- greed (sans lobha)

- hate (dosa)

- delusion (moha)

- conceit (māna)

- wrong views (micchāditthi)

- doubt (vicikicchā)

- torpor (thīnaṃ)

- restlessness (uddhaccaṃ)

- shamelessness (ahirikaṃ)

- recklessness (anottappaṃ)

From these ten arise all of our suffering. When we hate, we have violence — at the extreme, even war. When we are deluded, our incorrect perceptions lead to more suffering. When we are greedy, we want more, more, more. It is against the ten poisons that Buddha focused his skillful teaching methods and the 84000 teachings.

One root of suffering to be “cut” is anger.

Skillful means — the big “misunderstanding”

In this series of ten features, we will explore all ten of these poisons, from the unique view of the remedies, Buddha taught for different personalities and types of students. This, of course, gave rise to the multiple traditions in Buddhism — all of which are correct, perfect paths. It may seem that the Zen Buddhist is in no way similar to the Vajrayana Buddhist with the more exotic yogas, or the Pureland Buddhist who focuses on one goal. Nothing could be further from the core truth. All have the same goal. The methods vary, skillfully, based on the student.

The Chan and Zen path might lead one student to realizations while putting another to sleep. Vajrayana rituals and visualizations may seem overly complicated to some, yet are the perfect vehicle for a busy, monkey mind. The Elder School Sutta teachings are perfect teachings for those ready to renounce, while Mahayana Sutra teachings are ideal for people more focused on the well-being of everyone else in a more mundane samsaric existence. Tantra — which itself has multiple levels of various complexities — seems impenetrable to many, or even impossible to practice at times, yet it is this depth of detail that breaks down the perceptions of overly rigid minds.

Mindfulness meditation, as developed by Buddha and used by Buddhists for thousands of years, helps us stimulate the “rest and digest” response, with positive benefits on our health. This is just one method that helps us cut the discursive mind, even if only for a moment.

It’s all a matter of perspective. It is this perspective we’ll try to bring in this series, where we analyze methods from each tradition of Buddhism for each of the poisons. How does the Elder Path Sutta teachings remedy anger? How does Mahayana approach the same poison? Why is the Zen or Chan method so perplexing? And how is it possible that meditating on the ferocious form of Yamantaka with all those faces, arms and legs, a remedy for anger of the worst kind?

Poison by Poison, we explore, the Ten Kleshas and the many ways Buddha taught us to cut them.

Ultimately, the Buddhist path is a self-help path. We may walk with Sangha, friends, and community — and seek guidance from teachers — but the actual activities of meditation are solitary ones. Many great yogis of the past retired to isolated caves to meditate — to remove the distractions and still the mind.

Self-transformation is the key

Buddhism has always been a path of self-transformation. The Buddha was not just a teacher of Dharma, but also a model for how we can use the Dharma to change ourselves.

In the Pali Canon, he is recorded as saying, “Be lamps unto yourselves. Be a refuge unto yourselves. Take it upon yourselves to lead the way” (Samyutta Nikaya v. 353)

It is because we are told we can only rely on ourselves (ultimately) that Buddha taught so many methods. Some of them even seem “contradictory.” Buddhism’s Ten Poisons — the Ten Kleshas of Samsara, and their Antidotes — are the practical and crucial teachings of Buddha.

Peaceful Buddha scene at Phuket Pukei island Thailand.

Buddha — the self-help teacher

It is this attitude of self-reliance and self-transformation that is at the root of all Buddhism. And it is this attitude that we must bring to our exploration of the Ten Kleshas.

There is no easy way out. No pill we can take, no magic ritual we can perform that will simply cure us of our poisons. It’s up to us. We have to do the work.

But, as Buddha said, “With diligence, you can overcome all things” (Dhammapada v.334)

So let’s get started on the path of cutting the Ten Poisons!

84000 Teachings and frame of reference

In Buddhism, notably in Tibetan Buddhism, which embraces all of the paths, it is said there are 84,000 teachings from Buddha. While the core Suttas, often known as “Pali Sutta”

In each of the ten features in this series, we’ll focus on one poison, following a unified format. Let’s call it a “frame of reference.” For many of us, we use methods from all traditions.

An 84000-story building — or a world-sized tree with 84,000 branches

Choose your own metaphor — deep roots of the mythological world tree, or an 84,000-floor skyscraper. The world tree is a metaphorical tree in ancient myths (found, curiously, in many cultures around the world‚ that represents the universe.

The symbolic world tree as a metaphor.

The roots of this tree are as deep as its vast, unlimited branches. Each of those branches can be thought of as one of the 84,000 teachings. The vast roots can be seen as the initial core teachings given by Buddha at Deer Park.

Or, a more modern metaphor, the 84,000-floor skyscraper. In this case, likewise, the foundation must be incredibly deep and strong.

In either case, the roots or the foundation, are the metaphors for the earliest teaching at Deer Park, the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path. All future teachings enhance the original core message, but they do not depart from it.

In each feature, we’ll offer the “cut” remedies skillfully taught in:

- Elder Sutta

- Mahayana Sutra

- Pureland methods

- Zen / Chan methods

- Vajrayana and esoteric methods

We hope to show that as much as the methods may appear quite different, the ultimate destination remains the same.

Come along with us now, over this series of 10 additional features, as we focus one-by-one on each of the 10 Kleshas (poisons) and how the different traditions offer various prescriptions as a cure.

The 10 Kleshas of Buddhism

Each of the next ten features will focus on one Klesha or poison

- greed (sans lobha)

- hate (dosa)

- delusion (moha)

- conceit (māna)

- wrong views (micchāditthi)

- doubt (vicikicchā)

- torpor (thīnaṃ)

- restlessness (uddhaccaṃ)

- shamelessness (ahirikaṃ)

- recklessness (anottappaṃ).

Part one, the Poison of Greed, will publish soon!