How is it possible that Buddha predicted the sun would consume the earth in roughly 7.5 billion years – a theory scientists only recently confirmed? That places Buddha at least 2500 years ahead of modern science — in linear time.

Perhaps the answer lies in another temporal teaching of the Buddha when he spoke of time as non-linear. He also spoke of an unlimited multiverse with countless universes. Today, quantum physics proposes the same concept. (along with Mavel Comics and Hollywood.)

Buddha taught cause and effect, and temporal and cosmological mechanics long before it was a notion in modern times. In this in-depth feature, we dive into the correlations between Buddha’s temporal and cosmological teachings — and today’s modern scientific theories and understandings, citing several key Sutras:

- Agganna Sutta and Digha Nikaya

- Avatamsaka Sutra

- Mahavairocana Sutra

- Lotus Sutra

Related Features:

How is it possible — 3 possibilities

How is it possible? There are three clear possibilities:

• The Sutra explanation: Buddha became Enlightened, at which point he saw all his lives, all times and all universes simultaneously and omnisciently (this is the Sutra explanation)

• Since time is non-linear, he could see all of times, as stated in sutras: past, present, future as one.

• The non-Buddhist explanation: he was the most advanced philosopher of all time — far transcending any philosopher or scientist since.

Introduction — Buddha, Spiderman, and the multiverse

‘Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse,’ ‘Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness,’ and ‘Rick and Morty’ – are all recent stories that feature the multiverse. The concept of parallel universes has captured the public’s imagination for years, with more and more people becoming interested in the idea that there could be an infinite number of versions of themselves out there somewhere.

A recent film featuring the multiverse: Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness:

The recent Asian-American blockbuster ‘Everything, Everywhere, All At Once’ is perhaps the closest-related work to Buddhism. After the main character figures out how to tap into her own alternate personalities, the film culminates in a beautiful scene where the protagonist understands that only kindness in her reality will save her from a life of fear and pain.

Hollywood blockbusters and best-selling novels often depict scientific discoveries as eureka moments, whereby a lone individual has a sudden, groundbreaking realization that changes everything. In reality, however, most scientific advances are the result of the gradual accumulation of knowledge over time. And in some cases, concepts that are considered cutting-edge today were actually first proposed centuries ago.

This is certainly the case with the multiverse theory in quantum physics, which posits the existence of an infinite number of parallel universes. This article will explore the similarities between the multiverse theory and Buddhist teachings, as well as how the two can be used to explain some of the most baffling aspects of our reality.

The multiverse from a scientific standpoint

Before we can compare the multiverse theory to Buddhist teachings, it is first necessary to understand what scientists mean when they talk about the multiverse.

In the most basic sense, the multiverse is the hypothetical set of finite and infinite possible universes, including the universe we live in. Within the framework of quantum mechanics, our universe is just one among an infinite number of universes that exist in parallel.

The multiverse theory was first proposed (other than by Buddha) by mathematician and physicist Hugh Everett in the 1950s as a way to explain the apparent wave-like behavior of subatomic particles. Everett’s Many-Worlds Interpretation (MWI) of quantum mechanics suggests that every time a quantum event takes place, the universe splits into multiple universes, with each universe following a different path determined by the outcome of the event. [1]

For example, if you were to observe a quantum event, such as an atom decaying, you would see it decay in a certain way. But in another universe, that atom might have decayed in a different way. In other words, every time a quantum event takes place, there are an infinite number of universes in which that event plays out in different ways.

The famous theoretical physicist Stephen Hawking also believed in the existence of the multiverse. He was a firm advocate of string theory, which is a framework that attempts to unify all of the known forces in the universe. String theory predicted the existence of parallel universes and was Hawking’s final attempt to find a compelling reason for the Big Bang. [2]

There are a number of other scientific theories that also suggest the existence of parallel universes, but the vague and unprovable nature of these theories has led many scientists to be skeptical of the multiverse hypothesis. That being said, it is important to note that the multiverse is not just a scientific theory — it is also a philosophical concept with a long history.

What is Buddhist temporal cosmology?

Buddhist temporal cosmology is the Buddhist belief concerning the absolute past, present, and future of the universe. It’s essential to understand that in Buddhist beliefs, no god nor Buddha created the stars, planets, or galaxies. All things in the cosmos come into being and pass away due to conditions.

According to this doctrine, there is no beginning or end to time; rather, it is infinite and cyclical. This view is also adopted in Hindu cosmology and is known as the “Wheel of Time.” Like the seasons and life on Earth, The universe goes through an endless cycle of creation, destruction, and rebirth.

Time is measured in units known as “mahākalpa,” which translates to “Great Eon.” It is unclear how long a mahākalpa actually is, but it is said to be incredibly long — so long, in fact, that it is effectively infinite. We’re talking billions and billions and billions of years. A moment during the mahākalpa is simply called Kalpa and is said to be the time it takes for a universe to form, grow, mature, and decay. [3]

In Buddhist Cosmology, the end of one mahākalpa is followed by the complete destruction of the universe. All beings in the universe — humans, animals, plants, gods, demons, and so on — are annihilated. Once the universe has been destroyed, a new mahākalpa begins, and the cycle starts anew.

In parallel, scientific research has found that the universe is expanding and will continue to expand until it reaches a point where it becomes so large that gravity causes it to collapse in on itself — effectively resetting the universe in a “Big Crunch.” The Big Crunch would eventually lead to a new Big Bang, and the cycle would start anew. [4]

So, in a way, the Buddhist concept of the mahākalpa is similar to the scientific concept of the Big Bang and Big Crunch.

Buddhist Sutras and the Multiverse

Now that we have a basic understanding of Buddhist temporal cosmology let’s take a look at how the concept of the multiverse is described in Buddhist Sutras.

In the movie “Little Buddha” the moment of Shakyamuni Buddha’s Enlightenment is portrayed beautifully by Keanu Reeves:

Flower Garland Sutra: Avatamsaka Sutra

As one of the most important Mahayana Sutras, the Flower Garland Sutra (Avatamsaka Sutra) is a massive text that consists of dozens of chapters. It’s a complex and dense read, to say the least, but it contains some of the most comprehensive descriptions of the multiverse in all of Buddhist literature. [5]

Written at least 500 years after the Buddha’s death, the Avatamsaka Sutra is often described as the Buddha’s highest teaching. In this sutra, the Buddha describes a vast and infinitely- interconnected cosmos that consists of an infinite number of buddha realms.

These buddha realms are not just parallel universes — they are also interconnected, with each realm containing an infinite number of other realms. Furthermore, each plane contains an infinite number of beings, and each being includes an endless number of buddha realms. In other words, everything is connected to everything else, and reality — as we think we perceive it — is ultimately beyond our current understanding.

Emptiness is also a recurring theme in The Flower Garland Sutra. The sutra states that everything is empty and void of inherent existence. The perception “that the fields full of assemblies, the beings and eons which are as many as all the dust particles, are all present in every particle of dust.”

This idea of emptiness, or that everything is interconnected and interdependent is a central tenet of Buddhism, and it’s also a key concept in quantum physics.

In quantum mechanics, particles are not truly particles — they are actually waves of probability that only become particles when observed. Furthermore, these particles are not isolated from each other — they are all interconnected and interdependent. This interconnectedness gives rise to the strange phenomenon of quantum entanglement.

Finally, the concept of “self” is also called into question in The Flower Garland Sutra. Supported is the theory that the Buddha himself was a universe, with each one of his pores representing countless vast oceans. From the macroscopic to the microscopic, everything is a reflection of everything else.

Now that we have microscopes, we know that there actually is an entire ecosystem living within and on our skin and that we are made up of an infinite number of cells. So, the Buddha was right — we are all universes within universes.

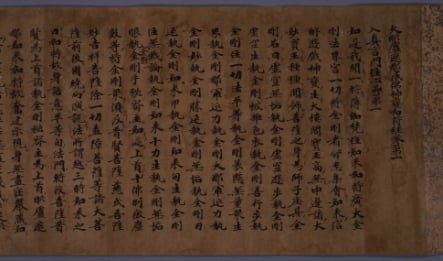

Mahavairocana Sutra

Next, let’s take a look at the Mahavairocana Sutra, another important Mahayana Sutra that was written around the same time as the Avatamsaka Sutra. To understand this sutra, we must eliminate any preconceived Western notion of linear time. We are taught that the universe began and will end, but this is not the case in Buddhist cosmology.

In the Mahavairocana Sutra, time is cyclical — it goes on forever and is never-ending. Furthermore, everything exists simultaneously — past, present, and future all exist at the same time. This idea may be hard to wrap our linear minds around, but it’s actually not that far-fetched. [6]

In quantum mechanics, particles do not have a definite past or future — they exist in a state of superposition, which means that they exist in all possible states simultaneously. That being said, the Mahavairocana Sutra supports the theory that the Buddha was born thousands of times in different universes and that he will be born again in the future.

Thus, he is not here to save the Earth or to be our personal savior — he is simply one of many to show us the way to enlightenment. And he does so in a thousand different ways, in a thousand different universes, all at the same time.

Vairochana, who is the Buddha of this particular sutra, is also known as the “Illuminator” or the “Great Sun Buddha.” He represents the enlightened mind, and his name literally means “clear light. He is even thought to be made up of all the photons in the universe.

If you’ve ever seen a statue or painting of the Vairochana, you might notice a thousand petals on his throne. These petals represent the thousand buddha realms, which might be used to represent the multiverse.

Dhamma or Dharma

Another important concept in Buddhism is Dhamma. It represents the truth of the way things are and is often described as “the teaching of the Buddha.” In one of those teachings, the Buddha says:

“As a net is made up of a series of ties, so everything in this world is connected by a series of ties. If anyone thinks that the mesh of a net is an independent, isolated thing, he is mistaken. It is called a net because it is made up of a series of interconnected meshes, and each mesh has its place and responsibility in relation to the other meshes.” [7]

There is no independence, and everything is interconnected. This is a major theme in Buddhism, and quantum mechanics also supports it. According to Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity, space and time are not absolute but are relative to the observer. As such, space does not exist independently of objects, and time does not exist independently of events.

Zen master D. T. Suzuki made this point perfectly when he said:

“By emptiness of self-aspect or self-character, therefore, is meant that each particular object has no permanent and irreducible characteristics to be known as its own.”

In other words, everything is in a state of flux, and nothing has a permanent, unchanging nature.

Furthermore, Dhamma’s 31 planes of existence are also worth noting. In the Mahayana tradition, these planes are known as the Buddha realms, and they represent different levels of reality. After someone dies, they are reborn into one of these realms based on their karma. They are divided into these main categories:

- The sensuous realm: This is where humans and animals reside. It is a world of suffering because we are subject to the pain of birth, old age, sickness, and death.

- The fine-material realm: In this realm, beings are free from the pain of birth, old age, sickness, and death. However, they are still subject to the pain of change. They have a subtle body, making them susceptible to the pleasures and pains of the physical world.

- The immaterial realm: This is a realm of pure consciousness, where devas, or celestial beings, reside. They are not subject to the pain of birth, old age, and sickness, since they don’t have physical bodies. However, this means they can no longer hear the Buddha’s teachings.

We can draw a parallel between these realms and the different quantum states that particles can exist in. Just like particles, we can exist in different quantum states depending on our karma. Upon our death, we will be reborn into one of these states based on our actions in this life.

Agganna Sutta

The Agganna Sutta, which can be found in the Digha Nikaya, is a Buddhist scripture that describes the evolution of the universe and the human race. In this sutta, the Buddha talks about world evolution and the beginning of life on Earth. It mainly revolves around a discussion with two brahmins, Bharadvaja and Vasettha.

After being insulted by their caste, the two brahmins go to the Buddha to ask about their origins. The Buddha then proceeds to tell them about the evolution of the universe and how humans came to be. He starts by describing the formation of the universe, which he says was destroyed millions of years ago and has evolved to its present state over many years. He then talks about the formation of life and social structures on Earth. [8]

While he doesn’t explicitly mention the multiverse in this sutta, we can see that the Buddha is talking about a world that is constantly changing and evolving. This is in line with the idea of the multiverse, which states that there are an infinite number of universes, each with its own set of changes.

He goes on to highlight the nature of “becoming,” and how the universe and everything in it are constantly changing. He talks about how beings are born, age, and die; how they rise and fall in social status; and how they experience pleasure and pain. He ultimately asserts that all of this is due to karma, or the law of cause and effect.

Lotus Sutra

Perhaps one of the most well-known Buddhist scriptures, the Lotus Sutra, is a Mahayana text that describes the Buddha’s teachings on emptiness and selflessness. In this sutta, the Buddha talks about how he achieved enlightenment through his practice of selflessness. He gives credit to the thousands of Buddhas who have come before him and asserts that all beings have Buddha nature. [9]

“Those Buddhas of the ages past,

Those of the times to come,

Those Buddhas of the present time,

Forever do I reverence.”

The Lotus Sutra is significant because it’s one of the first texts to talk about the idea of the Buddha realms, or different levels of reality. In this sutta, the Buddha uses plural forms when referring to himself and other Buddhas, which suggests that there are multiple Buddhas in different realms. This is in line with the idea of the multiverse, which states that there are an infinite number of universes, each with its own set of changes.

The Buddha goes on to talk about the Bodhisattva path, which is the path of selflessness and compassion. He describes how Bodhisattvas can help all beings, regardless of whether they are human or non-human. This is significant because it shows that the Buddha is concerned with the welfare of all beings, not just humans.

It is not the first time he has hinted at alien lifeforms, although they are never explicitly mentioned in the Lotus Sutra. Everything is open to interpretation. Maybe the other Buddhas were simply other humans who had not yet been born. Maybe they were non-human beings from other realms who had come to help the Buddha in his mission. Or maybe, as some scholars believe, the Buddha was hinting at the existence of intelligent life in other universes.

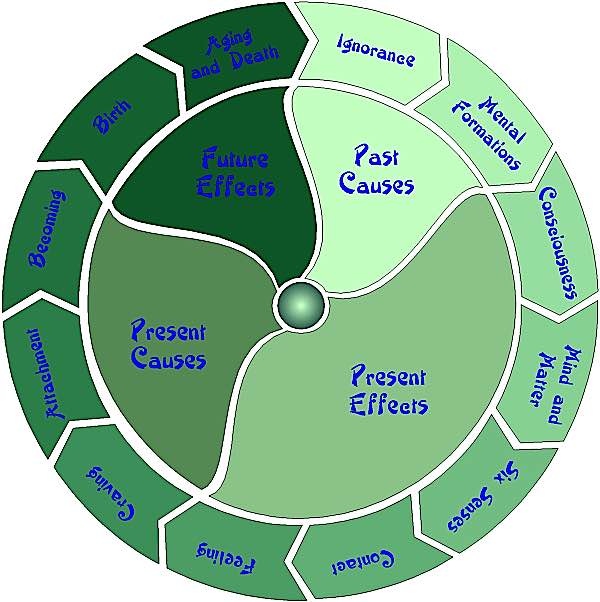

Pratitya-Samutpada

Speaking of karma, it’s worth mentioning the law of cause and effect, which is known as Pratitya-Samutpada in Buddhism. The doctrine states that all dharmas, or things, arise in dependence on other dharmas. In other words, everything is interconnected, and nothing can exist independently. As such, our universe could not exist without the existence of other universes. [10]

Another highlight here brings us back to the Big Bang and Big Crunch theory. As we know, the universe is expanding and will eventually reach a point where it starts to contract again. The law of cause and effect tells us that one causes the other; in this case, the Big Bang is the cause, and the Big Crunch is the effect.

This theory also ties in with the idea of rebirth. Just as the universe goes through a cycle of expansion and contraction, so do we go through a cycle of birth and death. Our actions in this life will determine our rebirth.

This law is often described as a “chain of causation,” because it shows how one thing leads to another. For example, if we plant a seed, it will grow into a tree. The tree will then produce fruit, which we can eat. This act of eating the fruit will then cause us to experience pleasure. At the same time, someone else may see us eating the fruit and feel jealous. The feeling of jealousy will then cause them to act in a negative way towards us.

Three universal truths

Finally, we come to the three universal truths, which are the cornerstone of Buddhist teachings. These aren’t to be confused with the four noble truths, which pertain to suffering, desire, and the path to liberation. The three universal truths are:

- All things are impermanent.

- Impermanence leads to suffering, making life imperfect

- The self is not personal and unchanging.

As we can see, these truths all tie in with everything we’ve talked about so far. The first truth tells us that everything is impermanent or in a state of flux. As big and mighty as our universe might seem, it is constantly changing and will one day come to an end. As for the third truth, it speaks to the idea of the multiverse—that we are not alone in this vast expanse and that there are an infinite number of other universes out there.

It’s also worth noting that the three universal truths are often described as “the three characteristics of existence.” This is because they highlight the nature of life. In science, a famous quote by physicist Antoine Lavoisier says,

“Nothing is lost, nothing is created, everything is transformed.”

We can apply this same logic to the three universal truths. All things are impermanent, but this doesn’t mean they cease to exist. Rather, they are simply transformed (or reborn) into something else.

Possible explanations for these links

So, how can we explain the similarities between Buddhism and science? Well, there are a few possible explanations. [11]

The first is that the Buddha was a very insightful man who deeply understood the world around him. In fact, many of his teachings were based on his own observations and experiences. Given that he lived over 2,500 years ago, it might be surprising to learn that his teachings are still relevant today. But this shows how far ahead of his time he was.

It’s worth noting that while these teachings are valid after some analysis, they weren’t as specific as modern theories. In some ways, the Buddha was more like a philosopher than a scientist. He would often use stories and metaphors to illustrate his points rather than getting bogged down in the details.

If you believe in reincarnation or in the notion of non-linear time — which most Buddhists do — then it becomes clear that the Buddha accumulated all this knowledge over the course of his many lifetimes — which are non-linear. It the sutras it is stated that when Buddha attained Enlightenment, he saw all his past and future lives simultaneously.

His having seen it previously would explain how he predicted the inevitable destruction of the Earth by the Sun. Today scientists agree with the Buddha’s assessment — In roughly 7.5 billion years, the Sun will expand and consume the Earth.

Another explanation is that Buddhism has been influenced by science over the years. As our understanding of the universe has grown, so has our understanding of Buddhism. In fact, many modern Buddhists are quick to point out the connections between their religion and science.

Unlike some theologies and spiritual paths, Buddhism does not clash with science. In fact, many Buddhists believe that their religion is compatible with science. This is likely because Buddhism is more of a way of life than a dogmatic religion. As such, it’s open to new interpretations and understandings.

Finally, it’s also possible that there are no concrete explanations for the similarities between Buddhism and science. It might be a pure coincidence that they share so many commonalities.

Why does Buddha speak of the cosmos?

Now that we’ve looked at some of the possible explanations for the similarities between Buddhism and science, let’s take a closer look at why the Buddha would have even brought up the topic of the cosmos in the first place.

First and foremost, it’s important to remember that the Buddha did not believe that understanding the ins and outs of the universe was necessary for enlightenment. In fact, he discouraged his followers from wasting their time on such things.

So, why would he take the time to talk about the cosmos? Well, there are a few possible reasons. First, it’s important to remember that the Buddha was not just a religious leader but also a teacher. And as a teacher, he wanted his students to think for themselves and to question everything, including his own teachings.

The Buddha says: “Just as a goldsmith would test his gold by burning, cutting, and rubbing it, so must you examine my words and accept them, not merely out of reverence for me.”

In essence, the Buddha was trying to get his followers to think critically and not just take his word for it. He insisted that if someone were to pursue the truth about the origins or future of our universe, they should investigate astronomy, cosmology, and other scientific disciplines for themselves.

The Buddha also saw clear opportunities for metaphors and similes when talking about the cosmos. He used these to explain complex concepts in a way that his students could understand.

Should Buddhist spend time trying contemplating the multiverse?

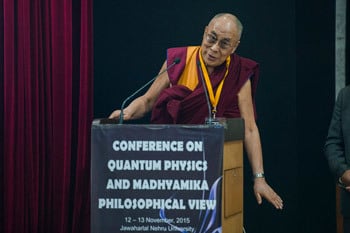

That is a personal question that every Buddhist has to answer for themselves. The Dalai Lama writes: [12]

“I don’t know whether the universe, with its countless galaxies, stars, and planets, has a deeper meaning or not, but at the very least, it is clear that we humans who live on this Earth face the task of making a happy life for ourselves… I have found that the greatest degree of inner tranquility comes from the development of love and compassion. The more we care for the happiness of others, the greater our own sense of well-being becomes.”

His Holiness goes on to say:

“It doesn’t matter how many universes are out there, and it doesn’t matter how many people are out there. We have no control over that. What we can control are our own minds. Everything that Buddha teaches is basically: return to your mind. We don’t have to do anything. We already know everything is changing—one thing leads to the next, it’s endless. We don’t have to run after that. What we have to do is return to ourselves.”

This quote shows that, while the Dalai Lama believes that understanding the cosmos is interesting, he also doesn’t think it’s necessary for enlightenment. Instead, he believes that Buddhists should focus on their own minds and on making a happy life for themselves. Ultimately, whether or not a Buddhist spends time trying to figure out the multiverse is up to them.

Connections and Buddhism

There are clear similarities between Buddhism and science when it comes to the multiverse.

From the Flower Garland Sutra to the Three Universal Truths, we understand that everything is connected and that everything is constantly changing. The multiverse is just one more example of this. Cause and effect, birth and death, these things are all a part of the natural order of things. And that applies to small beings like us as well as to gigantic things like universes.

While we may never get the truth about the multiverse – although never say never in the face of non-linear time – we can take comfort in knowing the Buddha himself encouraged us to question everything.

So, go out and explore the cosmos. Investigate astronomy and cosmology. And most importantly, don’t forget to return to your mind.

At the end of the day, that’s all that really matters.

Sources

[1] Plato on Standford edu>>

[2] Stephen Hawking Theory of Everything >>

[3] Buddhist Cosmology>>

[4] Astronomy How Stuff Works>>

[5] Avatamsaka Sutra>>

[6] Maha Vairocana Sutra on Buddha Weekly >>

[7] Parallel Universes Dhamma Wiki>>

[8] Buddhism Universal Theory on Tricycle>>

[9]>” href=”https://encyclopediaofbuddhism.org/wiki/Pratityasamutpada” target=”_blank” rel=”noopener”>Pratityasamutpada>>

[11] Buddhist cosmology>>

[12] Countless Galaxies>>