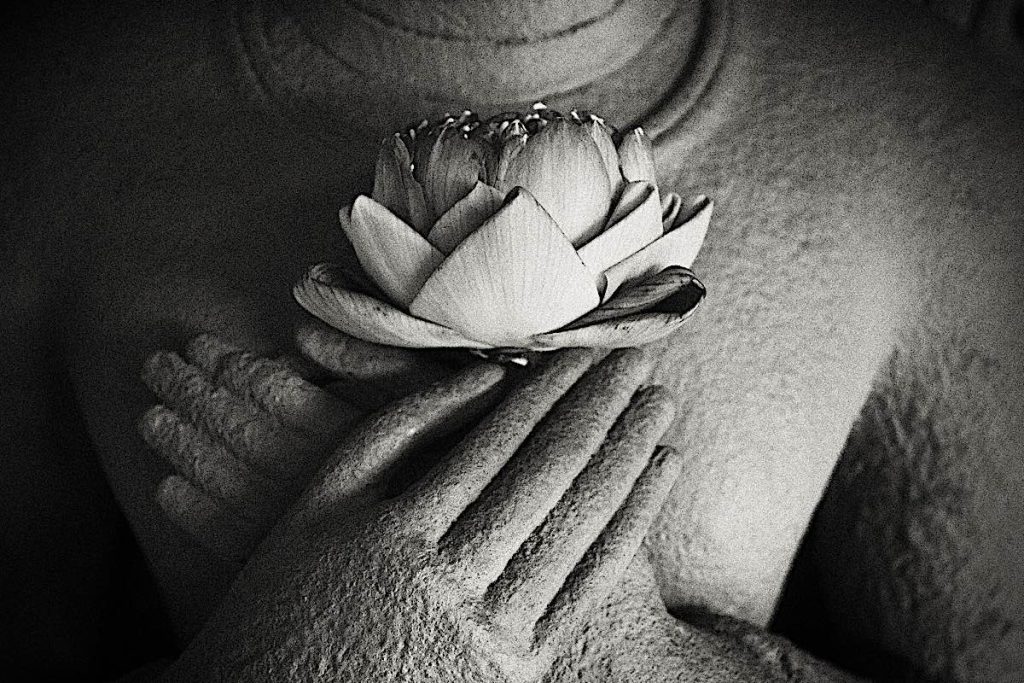

To understand the origins of Chan or Zen Buddhism, we have to go back to the “Flower Sermon.”

This sermon, given by the Buddha himself, is at the heart of Chan — also known as Zen in Japan or Seon in Korea.

In the Flower Sermon, the Buddha gathered his disciples together for a talk on Dharma. Instead of speaking, however, the Buddha simply held up a lotus flower in front of him without saying a word.

Everyone in the assembly was trying to make sense of the Buddha’s message, waiting for him to speak. But he never did.

The monks were baffled, but one of them, Mahakasyapa, suddenly understood the Buddha’s meaning and smiled.

The Buddha said,[1]

“I possess the true Dharma eye, the marvelous mind of Nirvāṇa, the true form of the formless, the subtle Dharma gate that does not rest on words or letters but is a special transmission outside of the scriptures. This I entrust to Mahakasyapa.”

This sermon marks the beginning of Chan Buddhism.

By Dave Lang

The origins of Chan Buddhism in China

The name “Chan” comes from “dhyana,” the Sanskrit word for “meditation,” which is central to Chan practice.

The roots of Chan Buddhism in China can be traced back to the 6th century AD when it was introduced by an Indian monk named Bodhidharma.

Bodhidharma is said to be the first patriarch of Chan Buddhism, although some texts establish the line of descent all the way back to

Mahakasyapa, the monk who received the Buddha’s teaching in the Flower Sermon. Bodhidharma would be the 28th patriarch in this line.

Bodhidharma is an essential figure in Chan history because he is credited with bringing the practice of meditation to China.

See our previous features on the Great Bodhidharma

The heart of Chan Buddhism is the practice of meditation

In Chan, meditation is not just a means to calm the mind and develop concentration. It is also a tool for recognizing the true nature of reality and achieving enlightenment, or liberation from the cycle of birth and death.

Bodhidharma taught that the Dharma could not be grasped by the intellect alone through the study of the scriptures. It is necessary to be able to experience it directly rather than through intellectual understanding.

That is why the Buddha taught his disciples in the Flower Sermon that the way to enlightenment is through the heart, not the mind.

The early Chan Buddhist communities gathered around charismatic teachers believed to have been enlightened and considered patriarchs, descending directly from Bodhidharma.

With the fourth patriarch after Bodhidharma, Daoxin, Chan began to take on a distinctly Chinese flavor as a separate school.

Our past related features on Chan/Zen

The East Mountain teachings

In the 7th Century, Daoxin and Hongren, his successor, brought a new style of teaching to Chan that came to be known as the “East Mountain teachings,” named after the East Mountain Temple established by Daoxin on the Twin Peaks in Huangmei.

This teaching style de-emphasized the importance of scriptures and rules and instead focused on personal experience and meditation.

It was during this time that the East Mountain community was established.

The community was the first time that Chan monks lived and studied together in an organized way, a change from the earlier Indian tradition of monks traveling and teaching individually.

This community lifestyle suited the Chinese society, which tended to be more group-oriented, and helped Chan Buddhism to take root in China.

The Southern School

The sixth and last ancestral founder, Huineng, is said to have been one of the greats of Chan history. All surviving schools of Chan consider him their ancestor.

In the 8th Century, there was a split in Chan Buddhism. A successor of Huineng, a monk named Shenhui, created a line of teaching known as the “Southern School,” in opposition to the East Mountain Teaching, also known as the “Northern School.”

The main difference between the two schools was their understanding of Huineng’s teachings.

Shenhui believed that only those who had received direct transmission from Huineng could attain enlightenment, while the East Mountain school believed that anyone could reach enlightenment through their own efforts.

They also had a different view on how you could achieve enlightenment.

The Southern School believed that enlightenment could be achieved through sudden realization, while the Northern or East Mountain school believed that it was a gradual process.

Later on, in the Platform Sutra and through the teachings of Guifeng Zongmi, this split between sudden and gradual enlightenment was reconciled.

Zongmi believed that both sudden and gradual enlightenment were possible and that they were just two different stages on the same path.

It was possible to have a sudden realization of the Dharma, but it was still necessary to cultivate and practice in order to consolidate that realization and achieve full enlightenment.

The expansion of Chan to other countries

Eventually, the East Mountain teachings spread to other parts of China and beyond, to Tibet, Korea, and Japan.

In Tibet

Moheyan, a monk from the East Mountain Community, and other Chinese Chan Buddhists went to Tibet in the 8th Century.

Chan and Tantric Buddhists lived together for several centuries but were later replaced by the development of a unique form of Tibetan Buddhism.

Zen in Japan

In Japan, the school of Chan Buddhism that developed was called Zen.

The word “Zen” is actually a Japanese pronunciation of the Chinese word “Chan,” which both mean “meditation.” The Japanese monk Eisai is credited with bringing Chan to Japan in the 12th Century and establishing it as a separate school.

Eisai first came into contact with Chinese Chan Buddhism during a trip to China in 1168. He was so impressed with what he saw that after studying it for several years, he decided to bring Chan back to Japan. [2]

Eisai founded the Japanese Rinzai school of Zen, which is still one of the major schools of Zen in Japan today.

Zen in the West

Zen is a very popular form of Buddhism in the West, and it has had a significant impact on Western culture, especially in the fields of art, literature, and philosophy. It was first introduced to the West in the 19th Century by Japanese Zen teachers who came to Europe and the United States to spread the teachings of Buddhism.

In the 20th Century, the popularity of Zen in the West increased due in part to the writings of Westerners who had been influenced by

Zen, such as the Beat poets and writers like Alan Watts and D.T. Suzuki.

Today, there are Zen Centers and temples around the world teaching meditation and offering guidance in the practice of Zen.

The texts of Chan Buddhism

Although Chan Buddhism emphasizes personal experience over scriptural study, there are still a few key texts that have been important to the development of the tradition.

The most important texts in Chan Buddhism are the Lankavatara Sutra, the Platform Sutra, the Diamond Sutra, and the Heart Sutra.

Lankavatara Sutra

The Lankavatara Sutra contains the Buddha’s direct teaching, recounting his visit to the island of Sri Lanka [3]. In this text, the Buddha lays out the principles of Chan Buddhism, including the importance of meditation and personal experience over academic study.

Bodhidharma is said to have passed the text down to his disciple, Huike, and it has been an essential text in Chan ever since. This sutra teaches that consciousness is the only reality and that all things are created by the mind.

Platform Sutra

The Platform Sutra is a collection of the sayings and stories of the Sixth Patriarch of Chan, Huineng. The Platform Sutra is one of the most important texts in Chan Buddhism, and it has been highly influential in the development of Zen in China and Japan.

There are two main themes in this sutra. One is the unity in essence of conduct, meditation, and wisdom, and the other is the direct perception of your true nature. [4]

Diamond Sutra

The Diamond Sutra is one of the most widely read and studied sutras in Mahayana Buddhism. This sutra was written in India in the 4th or 5th Century and brought to China in the 6th Century.

The Diamond Sutra is important in Chan Buddhism because it contains the teachings of emptiness and the Buddha-nature, two central concepts in Chan.

Heart Sutra

The Heart Sutra is one of the most wide-reaching texts of Buddhism, covering more of Buddha’s teachings than any other sutra. This sutra is essential to Chan because it emphasizes the importance of emptiness, a key principle in Chan Buddhism.

The Heart Sutra famously states the profound statement of Avalokiteshvara: [5]

“Form is emptiness, emptiness is form.”

The principles of Chan Buddhism

The origins of Chan Buddhism are deeply rooted in the teachings of Mahayana Buddhism.

What Chan highlights is that Buddha achieved enlightenment through Dharma practice and meditation and not through study and intellectual understanding.

These are some of the main principles that constitute the foundation of Chan Buddhism.

Everything is created by the mind

The central principle of Chan Buddhism is that the mind creates all things. This includes both good and bad thoughts, as well as our perceptions of the world around us.

All of reality is a product of our own minds, and so it can be changed by changing our thoughts.

Chan Buddhists believe that we can only honestly know reality by directly experiencing it rather than through intellectual study.

Buddha-Nature

The Buddha-Nature is the inherent goodness in all beings. This principle is important in Chan Buddhism because it teaches that we are all capable of enlightenment, regardless of our current state.

It is the potential to awaken to our true nature, which is beyond thought and opinion.

Chan Buddhists believe that everyone has the Buddha-Nature, and so everyone has the potential to awaken to their true nature and attain enlightenment.

Some features on Buddha Nature

Emptiness – Shunyata

Emptiness is a central understanding in Chan Buddhism, and it is closely related to the idea of the Buddha-nature. Everything is empty of any fixed nature or essence, so everything is constantly changing. This includes our own sense of self, which is also empty. The realization of emptiness leads to a deeper understanding of the Buddha-nature, which is empty too.

Some important features on Shunyata or Emptiness

The importance of meditation

Chan Buddhists place a great emphasis on meditation as a way to experience reality directly and develop wisdom and compassion. Meditation is seen as a way to still the mind and see things clearly, without the filters of our thoughts and opinions.

Through meditation, we can come to understand our true nature and the nature of reality. Just like Buddha reached enlightenment through Dharma practice and meditation, so too can anyone else.

The teacher-student relationship

In Chan Buddhism, the relationship between teacher and student is viewed as essential to the awakening process. The teacher is seen as a guide who can help the student awaken to their true nature, and the student must have complete trust and faith in the teacher.

The teacher-student relationship is not about intellectual understanding but about a deep spiritual connection.

Chan Buddhism today

Today, Chan or Zen Buddhism is practiced all over the world, with centers in Europe, America, and Asia. Many people practice Chan Buddhism as a form of meditation, and others use it as a tool for personal growth and transformation.

In the West, Chan Buddhism has gained popularity in recent years, with more and more people interested in its teachings and practices.

It is often practiced as a form of meditation, and its tools are also used in therapy and counseling.

No matter what name it goes by, Chan or Zen, at its core, this practice aims to help us see reality clearly as it is through the practice of meditation. This way, we can achieve an understanding of the true nature of things and ultimately attain enlightenment.

References

[1]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chan_Buddhism

[2]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Japanese_Zen

[3]: https://www.patheos.com/library/zen/origins/scriptures

[4]: https://encyclopediaofbuddhism.org/wiki/Platform_Sutra

[5]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heart_Sutra