Recitation of the Diamond Sutra, or Vajra Cutter, is a vital indispensable practice, as recommended by many teachers, from His Holiness the Dalai Lama, to the great teacher Lama Zopa Rinpoche — to nearly every Mahayana teacher of all lineages.

Why is this practice so exalted? Why is the merit so vast? We try to answer these questions and end with an English version of the Sutra — suitable for chanting or recitation.

In Buddha’s words — the most important

Buddha himself, in answer to Sabhut’s question in this sutra, describes the teaching’s importance this way:

Subhūti, this foremost pāramitā that the Tathāgata speaks of is not a foremost pāramitā, and is thus called the foremost pāramitā.

In just 6000 words — the entire essence of Buddha’s teaching on Wisdom is expressed.

And, for those who really have no time to recite this sutra — ass unlikely as that is — you could recite the mantra from the appendix of this great sutra as a practice — while holding in mind the profound meaning of the sutra:

-

namo bhagavatīprajñāpāramitāyai

-

oṃ īriti īṣiri śruta viṣaya viṣaya svāhā

Note: One of the translations we cite here — there are many to chose from — is the elegant modern version by the great Zen Master Thich Nhat Hanh. (This is an excerpt with a link to the full text.) We also include another translation of the full text.

Six short chapters — 32 sections

Why is it so important? In six short chapters — each chapter shorter than the previous one — as if the words are dissolving into the essence of “emptiness” — is revealed the essence of Mahayana Buddhism. In some traditions, the Sutra describes four main points of practice:

- giving without attachment to self

- liberating beings without notions of self and other

- living without attachment

- and cultivating without attainment.

This can be otherwise thought of as 32 sections. [See the English translation below.]

Aside from the points of practice, you could also say — as with all the Prajnaparamita Sutras — that it explains the “true nature of ultimate reality.” After all, the theme is “the diamond that cuts through illusions.” As we cut through the illusions of Samsara, we leave behind fear and we find boundless compassion grows — unlimited Bodhichitta. The true nature or reality is expressed in various ways throughout the text, including this one verse translated by Bill Porter (Red Pine)[3]:

So you should view this fleeting world—

A star at dawn, a bubble in a stream,

A flash of lightening in a summer cloud,

A flickering lamp, a phantom, and a dream.

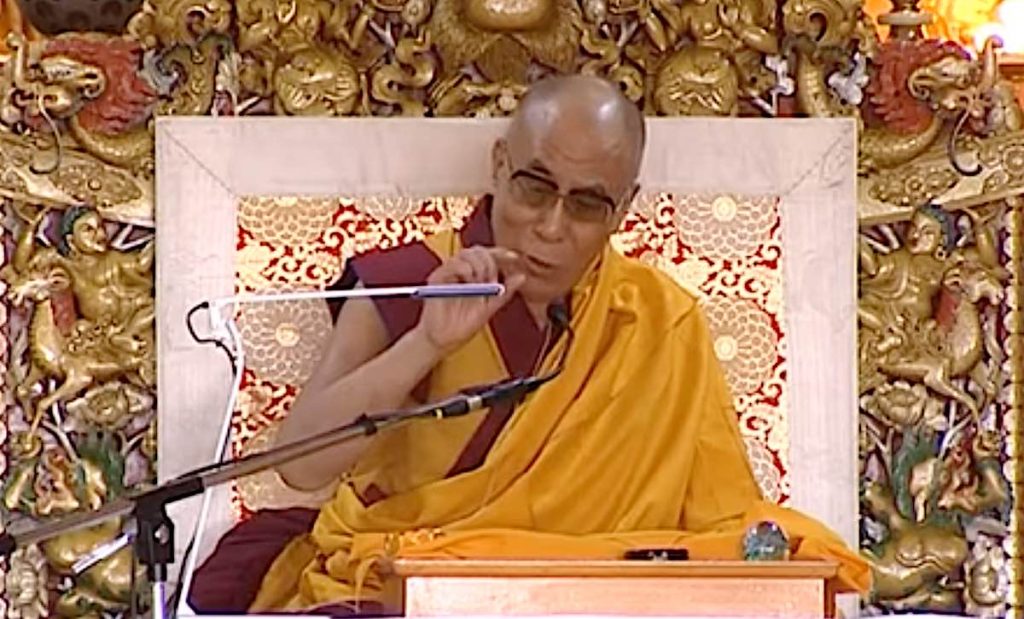

The Dalai Lama teaching (translated in English) on the Diamond Sutra or Vajra Cutter Sutra (day 1 of teaching) on Youtube:

A Sutra of Negation

You could say, the style of Buddha’s teaching in this sutra is negation. In various ways, throughout the sutra, Buddha negates our erroneous perceptions. Japanese Buddhologist Hajime Nakamura calls this negation the “logic of not” (na prthak).

For example:

- “As far as ‘all dharmas’ are concerned, Subhuti, all of them are dharma-less. That is why they are called ‘all dharmas’.”

- “Those so-called ‘streams of thought’, Subhuti, have been preached by the Tathagata as streamless. That is why they are called ‘streams of thought’.”

- “‘All beings’, Subhuti, have been preached by the Tathagata as beingless. That is why they are called ‘all beings’.”

For this reason, the Diamond Cutter sutra can be a lifetime of sutra. When you peel back the layers of teachings the message is simple. Yet, comprehending the message — beyond intellectual understanding — can take a lifetime.

For this reason, and others, Mahayana teachers recommend frequent recitation or — at least — reading of this short sutra. We have provided the entire English translation from two sources at the end of this feature.

Benefits of reciting Vajra Cutter Sutra

“The Vajra Cutter Sutra is unbelievable,” Lama Zopa Rinpoche taught. “It is one of the most profitable practices, because the root of all sufferings, yours and others, is the ignorance holding ‘I’ as truly existent—even though it is empty of that; and the ignorance holding the aggregates as truly existent, even though they are empty of that. The only antidote to cut that, to get rid of that and through which to achieve liberation, the total cessation of the suffering causes—delusions and karma—is the wisdom realizing emptiness. This is the subject of the Vajra Cutter Sutra, emptiness. So, each time you read it, it leaves such a positive imprint. Without taking much time, without much difficulty, it is easy to actualize wisdom.” [1]

This is a practice also recommended by nearly every Mahayana Buddhist teacher, and with good reason. This sutra forms the foundation of Mahayana practices. It is especially meritorious to recite this on Holy Days — and especially on one or all of the four Holy Days of Shakyamuni Buddha (the actual dates vary by traditions):

- Chotrul Düchen, the ‘Festival of Miracles’

- Saga Dawa Düchen, the ‘Festival of Vaishakha’

- Chökhor Düchen, the ‘Festival of Turning the Wheel of Dharma’

- Lha Bab Düchen, the ‘Festival of the Descent from Heaven’

The Perfection of Wisdom that cuts like a thunderbolt!

The Sanskrit title for the sūtra is the Vajracchedikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra, which may be translated roughly as the “Vajra Cutter Perfection of Wisdom Sūtra” or “The Perfection of Wisdom Text that Cuts Like a Thunderbolt”

Vajrcchedika literally translates as “diamond cut”: vajra literally translates either as “diamond” or “thunderbolt”; chedana, “to cut”; and prajñāpāramitā, “perfection of wisdom”. The Vajra Cutter Sutra is also known as the Diamond Sutra because of its great simile of the diamond that cuts all things.

It is called Vajra Cutter because it cuts through all wrong views, especially the view of a personal self (or soul) and all other views that give rise to suffering. The cutter here refers to the wisdom realizing emptiness—the Vajra Cutter Sutra shatters all our ordinary ways of thinking and sees things in an entirely different way.

The Vajra Cutter Sutra is one of the most famous Mahayana sutras and has been translated into many languages. In China, it was one of the earliest Buddhist texts to be printed using moveable type (during the Song dynasty), and is also found in Dunhuang manuscripts.

The Vajra Cutter Sutra consists of six chapters, with each chapter getting progressively shorter. This reflects the teaching that wisdom does not increase or decrease, but is always perfect and complete.

“In general, all the Prajñāpāramitā Sutras teach about emptiness—the way things really are—but this sūtra presents it more clearly than any of the others. If we can get even a glimpse of emptiness, then we have cut the root of samsara and planted the seed of Buddhahood. Therefore, Vajrasattva is very happy when we recite this sūtra.”

The Vajra Cutter Sutra was probably written in India sometime between the 1st century BCE and the 1st century CE. It was translated into Chinese by Kumārajīva during 404-413 CE.

The Vajra Cutter Sutra has been enormously influential in East Asian Buddhism, especially Chan Buddhism (Zen). The Vajra Cutter Sutra contains the famous line “form is emptiness; emptiness is form”, which is often cited as a summary of the Heart Sutra’s teaching on śūnyatā (emptiness).

The Vajra Cutter Sutra is also a major practice, chanted regularly in Tibetan Buddhist centers. In some Tibetan lineages, it is customary to recite the Vajra Cutter Sutra 100,000 times either as a foundation practice, or simply for the benefit of all sentient beings.

“No matter what kind of merit you generate—by reciting this sūtra, … doing prostrations or any other practice—if you can mix it with bodhicitta, then your merit becomes like an atomic bomb. It becomes incomparable; there’s no limit to the amount of merit you create. ” — Venerable Thubten Chodron

The four points of the sutra — or, what’s it about?

If there was every an inappropriate question regarding the Diamond Sutra it might be “What’s it about?” Why is it an odd question to ask?

In his commentary on the Diamond Sūtra, Hsing Yun describes the four main points from the sūtra as

- giving without attachment to self

- liberating beings without notions of self and other

- living without attachment

- and cultivating without attainment.

Yet, knowing this, do we now come close to penetrating the depths of this profound sutra?

Diamond Sutra in different lagnauges

Translations of this title into the languages of some of these countries include:

- Sanskrit: वज्रच्छेदिकाप्रज्ञापारमितासूत्र, Vajracchedikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra

- Chinese: 金剛般若波羅蜜多經, Jīngāng Bōrě-bōluómìduō Jīng; shortened to 金剛經, Jīngāng Jīng

- Japanese: 金剛般若波羅蜜多経, Kongō hannya haramita kyō; shortened to 金剛経, Kongō-kyō

- Korean: 금강반야바라밀경, geumgang banyabaramil gyeong; shortened to 금강경, geumgang gyeong

- Classical Mongolian: Yeke kölgen sudur[6]

- Vietnamese: Kim cương bát-nhã-ba-la-mật-đa kinh; shortened to Kim cương kinh

- Standard Tibetan: འཕགས་པ་ཤེས་རབ་ཀྱི་ཕ་རོལ་ཏུ་ཕྱིན་པ་རྡོ་རྗེ་གཅོད་པ་ཞེས་བྱ་བ་ཐེག་པ་ཆེན་པོའི་མདོ།, ’phags pa shes rab kyi pha rol tu phyin pa rdo rje gcod pa zhes bya ba theg pa chen po’i mdo

The practice is so important, the FPMT website dedicates extensive resources to the sutra, its practices, teachings and documents>>

The Diamond Sutra chanted in English

Excerpt of the Diamond Sutra by Thich Nhat Hanh:

Vajracchedikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra (in Sanskrit), Taishō 235

This is what I heard one time when the Buddha was staying in the monastery in Anathapindika’s park in the Jeta Grove near Shravasti with a community of 1,250 bhikshus, fully ordained monks.

That day, when it was time to make the almsround, the Buddha put on his sanghati robe and, holding his bowl, went into the town of Shravasti to beg for alms, going from house to house. When the almsround was completed, he returned to the monastery to eat the midday meal. Then he put away his sanghati robe and his bowl, washed his feet, arranged his cushion, and sat down.

At that time, the Venerable Subhuti stood up, bared his right shoulder, put his knee on the ground, and, joining his palms respectfully, said to the Buddha, “World-Honored One, it is rare to find someone like you. You always support and place confidence in the Bodhisattvas.

“World-Honored One, if sons and daughters of good families want to give rise to the highest, most fulfilled, awakened mind, what should they rely on and what should they do to master their mind?”

The Buddha said to Subhuti, “The Bodhisattva Mahasattvas master their mind by meditating as follows: ‘However many species of living beings there are—whether born from eggs, from the womb, from moisture, or spontaneously; whether they have form or do not have form; whether they have perceptions or do not have perceptions; or whether it cannot be said of them that they have perceptions or that they do not have perceptions, we must lead all these beings to nirvana so that they can be liberated. Yet when this innumerable, immeasurable, infinite number of beings has become liberated, we do not, in truth, think that a single being has been liberated.’

“Why is this so? If, Subhuti, a bodhisattva still has the notion of a self, a person, a living being, or a life span exists, that person is not a true bodhisattva.

“Moreover, Subhuti, when bodhisattvas practice generosity, they do not rely on any object—any form, sound, smell, taste, touch, or object of mind to practice generosity. That, Subhuti, is the spirit in which bodhisattvas practice generosity, not relying on signs. Why? If bodhisattvas practice generosity without relying on signs, the happiness that results cannot be conceived of. Subhuti, do you think that the space in the Eastern Quarter can be conceived of or measured?”

“No, World-Honored One.”

“Subhuti, can space in the Western, Southern, or Northern Quarters, above or below be conceived of or measured?”

“No, World-Honored One.”

“Subhuti, if bodhisattvas do not rely on any concept while practicing generosity, the happiness that results from that virtuous act is like space. It cannot be conceived of or measured. Subhuti, the bodhisattvas should let their minds dwell in the teachings I have just given.

“What do you think, Subhuti? Is it possible to recognize the Tathagata by means of bodily signs?”

“No, World-Honored One. When the Tathagata speaks of bodily signs, there are no signs being talked about.”

The Buddha said to Subhuti, “In a place where there are signs, in that place there is deception. If you can see the signless nature of signs, you can see the Tathagata.”

The Venerable Subhuti said to the Buddha, “In times to come, will there be people who, when they hear these teachings, have real faith in them?”

The Buddha replied, “Do not speak that way, Subhuti. Five hundred years after the Tathagata has passed away, there will still be people who appreciate the joy and happiness that come from observing the precepts. When such people hear these words, they will have faith that this is the truth. Know that such people have sown wholesome seeds not only during the lifetime of one Buddha, or even two, three, four, or five Buddhas, but have, in fact, planted wholesome seeds during the lifetimes of tens of thousands of Buddhas. Anyone who, for even a moment, gives rise to a pure and clear confidence upon hearing these words of the Tathagata, the Tathagata sees and knows that person, and they will attain immeasurable merit because of this understanding. Why?

“Because that person is not caught in the idea of a self, a person, a living being, or a life span. They are not caught in the idea of the Dharma or the non-Dharma; a sign or no-sign. Why? If you are caught in the idea of the Dharma, you are also caught in the ideas of a self, a person, a living being, and a life span. If you are caught in the idea that there is no Dharma, you are still caught in the ideas of a self, a person, a living being, and a life span. That is why you should not get caught in the idea that this is the Dharma or that is not the Dharma. This is the hidden meaning when the Tathagata says, ‘Bhikshus, you should know that the Dharma that I teach is like a raft.’ You should let go of the Dharma, let alone what is not the Dharma.”

The Buddha asked Subhuti, “In ancient times when the Tathagata practiced under the guidance of the Buddha Dipankara, did the Tathagata attain anything?”

Subhuti answered, “No, World-Honored One. In ancient times when the Tathagata practiced under the guidance of the Buddha Dipankara, he did not attain anything.”

“What do you think, Subhuti? Does a bodhisattva adorn a Buddha Field?”

“No, World-Honored One. Why? To adorn a Buddha Field is not in fact to adorn a Buddha Field. That is why it is called adorning a Buddha Field.”

The Buddha said, “So, Subhuti, all the Bodhisattva Mahasattvas should give rise to a pure and clear mind in this spirit. When they give rise to this mind, they should not rely on form, sound, smell, taste, touch, or object of mind. They should give rise to an intention with their minds not dwelling anywhere.”

“So, Subhuti, when bodhisattvas give rise to the unequaled mind of awakening, they should let go of all ideas. They should not rely on form when they give rise to that mind, nor on sound, smell, taste, touch, or object of mind. They should only give rise to the mind that is not dwelling anywhere.

“The Tathagata has said that all notions are not notions and that all living beings are not living beings. Subhuti, the Tathagata is one who speaks of things as they are, speaks what is true, and speaks in accord with reality. He does not speak falsely. He only speaks in this way. Subhuti, if we say that the Tathagata has realized a teaching, that teaching is neither true nor false.

“Subhuti, bodhisattvas who still depend on notions to practice generosity are like someone walking in the dark. They do not see anything. But when bodhisattvas do not depend on any object of mind to practice generosity, they are like someone with good eyesight walking under the light of the sun. They can see all shapes and colors.

“Subhuti, do not say that the Tathagata has the idea, ‘I will bring living beings to the shore of liberation.’ Do not think that way, Subhuti. Why? In truth there is no living being for the Tathagata to bring to the other shore. If the Tathagata were to think there was, he would be caught in the idea of a self, a person, a living being, or a life span. Subhuti, what the Tathagata calls a self essentially is not a self in the way that ordinary people say there is a self. Subhuti, the Tathagata does not consider those ordinary people as ordinary people. That is why he can call them ordinary people.

“What do you think, Subhuti? Can someone visualize the Tathagata by means of the thirty-two marks?”

Subhuti said, “Yes, World-Honored One. We should use the thirty-two marks to visualize the Tathagata.”

The Buddha said, “If you say that you can use the thirty-two marks to visualize the Tathagata, then is the Cakravartin also a Tathagata?”

Subhuti said, “World-Honored One, I understand your teaching. One should not use the thirty-two marks to visualize the Tathagata.”

Then the World-Honored One spoke this verse:

“Someone who looks for me in form

or seeks me in sound

is on a mistaken path

and cannot see the Tathagata.”

“Subhuti, if you think that the Tathagata realizes the highest, most fulfilled, awakened mind and does not need to use all the signs, you are wrong. Subhuti, do not think in that way. Do not think that when one gives rise to the highest, most fulfilled, awakened mind, one needs to see all objects of mind as nonexistent, cut off from life. Do not think in that way. One who gives rise to the highest, most fulfilled, awakened mind does not say that all objects of mind are nonexistent and cut off from life.”

After they heard the Lord Buddha deliver this discourse, the Venerable Subhuti, the bhikshus and bhikshunis, laymen and laywomen, and gods and asuras, filled with joy and confidence, began to put these teachings into practice.

Translated by Thich Nhat Hanh from the Vajracchedikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra (in Sanskrit), and the Chinese Taishō Revised Tripitaka, No. 235.

The Diamond That Cuts Through Illusion

Taishō Tripiṭaka volume 8, number 235. Translated by Trepiṭaka Kumārajīva in 401 CE, as Jin’gang Bore Boluomi Jing (金剛般若波羅蜜經).

Vajracchedikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra

Section 1: The cause of the Dharma assembly

Thus have I heard. At one time the Buddha was in Śrāvastī, residing in the Jeta Grove, in Anāthapiṇḍada’s park, along with a great saṃgha [gathering] of bhikṣus [monks], twelve hundred and fifty in all. At mealtime, the Bhagavān [‘holy one’, the Buddha] put on his robe, picked up his bowl, and made his way into the great city of Śrāvastī to beg for food within the city walls. After he had finished begging sequentially from door to door, he returned and ate his meal. Then he put away his robe and bowl, washed his feet, arranged his seat, and sat down.

Section 2: Elder Subhūti opens the question

From the midst of the great multitude, Elder Subhūti then arose from his seat, bared his right shoulder, and knelt with his right knee to the ground. With his hands joined together in respect, he addressed the Buddha, saying, “How extraordinary, Bhagavān, is the manner in which the Tathāgata [‘thus-gone’, the Buddha] is skillfully mindful of the bodhisattvas [‘sages’], and skillfully instructs and cares for the bodhisattvas! Bhagavān, when good men and good women wish to develop the mind of Anuttarā Samyaksaṃbodhi, how should their minds dwell? How should they pacify their minds?” The Buddha replied, “Excellent, excellent, Subhūti, for it is just as you have said: the Tathāgata is skillfully mindful of the bodhisattvas, and skillfully instructs and cares for the bodhisattvas. Now listen carefully, because your question will be answered. Good men and good women who wish to develop the mind of Anuttarā Samyaksaṃbodhi should dwell thusly, and should pacify their minds thusly.” “Just so, Bhagavān. We are joyfully wishing to hear it.”

Section 3: The true way of the Great Vehicle

The Buddha told Subhūti, “Bodhisattva-mahāsattvas [Great and holy sages] should pacify their minds thusly: ‘All different types of sentient beings, whether born from eggs, born from wombs, born from moisture, or born from transformation; having form or no form; having thought, no thought, or neither thought nor no thought — I will cause them all to become liberated and enter Remainderless Nirvāṇa.’ Thusly sentient beings are liberated without measure, without number, and to no end; however, truly no sentient beings obtain liberation. Why? Subhūti, if a bodhisattva has a notion of a self, a notion of a person, a notion of a being, or a notion of a life, he is not a bodhisattva.

Section 4: The wondrous practice of non-abiding

“Moreover, Subhūti, bodhisattvas should not abide in dharmas [rules] when practicing giving. This is called ‘giving without abiding in form.’ This giving does not abide in sounds, scents, tastes, sensations, or dharmas. Subhūti, bodhisattvas should practice giving thusly, not abiding in characteristics. Why? If bodhisattvas do not abide in characteristics in their practice of giving, then the merits [greatness] of this are inconceivable in measure. Subhūti, what do you think? Is the space to the east conceivable in measure?” “Certainly not, Bhagavān.” “Subhūti, what do you think? Is the space to the south, west, north, the four intermediary directions, or the zenith or nadir, conceivable in measure?” “Certainly not, Bhagavān.” “Subhūti, for bodhisattvas who do not abide when practicing giving, the merits are also such as this: inconceivable in measure. Subhūti, bodhisattvas should only dwell in what is taught thusly.

Section 5: The principle for true perception

“Subhūti, what do you think? Can the Tathāgata be perceived by means of bodily marks?” “Certainly not, Bhagavān. The Tathāgata cannot be perceived by means of the bodily marks. Why? The bodily marks that the Tathāgata speaks of are not bodily marks.” The Buddha told Subhūti, “Everything that has marks is deceptive and false. If all marks are not seen as marks, then this is perceiving the Tathāgata.”

Section 6: The rarity of true belief

Subhūti addressed the Buddha, saying, “Bhagavān, will there be sentient beings who are able to hear these words thusly, giving rise to true belief?” The Buddha told to Subhūti, “Do not speak that way. After the extinction of the Tathāgata, in the next five hundred years, there will be those who maintain the precepts and cultivate merit, who will be able to hear these words and give rise to a mind of belief. Such beings have not just planted good roots with one buddha, or with two buddhas, or with three, four, or five buddhas. They have already planted good roots with measureless millions of buddhas, to be able to hear these words and give rise to even a single thought of clean, clear belief. Subhūti, the Tathāgata in each case knows this, and in each case perceives this, and these sentient beings thus attain immeasurable merit. Why? This is because these beings are holding no further notions of a self, notions of a person, notions of a being, or notions of a life. They are holding no notions of dharmas [i.e. not blindly following laid rules] and no notions of non-dharmas. Why? If the minds of sentient beings grasp after appearances, then this is attachment to a self, a person, a being, and a life. If they grasp after notions of dharmas, that is certainly attachment to a self, a person, a being, and a life. Why? When one grasps at non-dharmas, then that is immediate attachment to a self, a person, a being, and a life. Therefore, you should neither grasp at dharmas, nor should you grasp at non-dharmas. Regarding this principle, the Tathāgata frequently says, ‘You bhikṣus should know that the dharma I speak is like a raft. Even dharmas should be relinquished, so how much more so the non-dharmas?’

Section 7: No obtaining, no expounding

“Subhūti, what do you think? Has the Tathāgata obtained Anuttarā Samyaksaṃbodhi? Is there any dharma the Tathāgata has spoken?” Subhūti replied, “Thus do I explain the true meaning of the Buddha’s teachings: there is no fixed dharma of Anuttarā Samyaksaṃbodhi, nor is there a fixed dharma the Tathāgata can speak. Why? The Tathāgata’s exposition of the Dharma [teaching] can never be grasped or spoken, being neither dharma nor non-dharma [being neither a fixed rule nor licence]. What is it, then? All the noble ones are distinguished by the unconditioned Dharma.”

Section 8: Emerging from the Dharma

“Subhūti, what do you think? If someone filled the three thousand great thousand-worlds with the Seven Precious Jewels in the practice of giving, would such a person obtain many merits?” Subhūti replied, “Very many, Bhagavān! Why? Such merits do not have the nature of merits, and for this reason the Tathāgata speaks of many merits.” “If a person accepts and maintains even as little as a four-line gāthā from within this sūtra, speaking it to others, then his or her merits will be even greater. Why? Subhūti, this is because all buddhas, as well as the dharmas of the Anuttarā Samyaksaṃbodhi of the buddhas, emerge from this sūtra. Subhūti, what is called the Buddha Dharma is not a buddha dharma.

Section 9: The appearance without appearance

“Subhūti, what do you think? Does a srotaāpanna have the thought, ‘I have obtained the fruit of a srotaāpanna?’” Subhūti replied, “No, Bhagavān. Why? ‘Srotaāpanna’ refers to one who has entered the stream, yet there is nothing entered into. There is no entry into forms, sounds, scents, tastes, sensations, or dharmas. Thus is one called a srotaāpanna.” “Subhūti, what do you think? Does a sakṛdāgāmin have the thought, ‘I have obtained the fruit of a sakṛdāgāmin?’” Subhūti replied, “No, Bhagavān. Why? ‘Sakṛdāgāmin’ refers to one who will return once more, yet there is nothing which leaves or returns. Thus is one called a sakṛdāgāmin.” “Subhūti, what do you think? Does an anāgāmin have the thought, ‘I have obtained the fruit of an anāgāmin?’” Subhūti replied, “No, Bhagavān. Why? ‘Anāgāmin’ refers to one who will not return, yet there is nothing non-returning. Thus is one called an anāgāmin.”

“Subhūti, what do you think? Does an arhat have the thought, ‘I have obtained the fruit of an arhat?’” Subhūti replied, “No, Bhagavān. Why? There is truly no dharma which may be called an arhat. Bhagavān, if an arhat has the thought, ‘I have attained the Arhat Path,’ then this is a person attached to a self, a person, a being, and a life. Bhagavān, the Buddha says that among arhats, I am the foremost in my practice of the Samādhi of Non-contention, and am the foremost free of desire. However, Bhagavān, I do not have the thought, ‘I am an arhat free of desire.’ If I were thinking this way, then the Bhagavān would not speak of ‘Subhūti, the one who dwells in peace.’ It is because there is truly nothing dwelled in, that he speaks of ‘Subhūti, the one who dwells in peace.’”

Section 10: The adornment of pure lands

The Buddha addressed Subhūti, saying, “What do you think? In the past when the Tathāgata was with Dīpaṃkara Buddha, was there any dharma obtained?” “No, Bhagavān. When the Tathāgata was with Dīpaṃkara Buddha there was truly no dharma obtained.” “Subhūti, what do you think? Do bodhisattvas adorn buddha-lands?” “No, Bhagavān. Why? The adornments of buddha-lands are not adornments, and are thus called adornments.” “Therefore, Subhūti, bodhisattva-mahāsattvas should thusly give rise to a clear and pure mind — a mind not associated with abiding in form; a mind not associated with abiding in sounds, scents, tastes, sensations, or dharmas; a mind not abiding in life. Subhūti, suppose a person had a body like Mount Sumeru, King of Mountains. Would this body be great?” Subhūti replied, “It would be extremely great, Bhagavān. Why? The Buddha teaches that no body is the Great Body.”

Section 11: Unconditioned merits surpass all

“Subhūti, suppose each sand grain in the Ganges River, contained its own Ganges River. What do you think, would there be many grains of sand of the Ganges River?” Subhūti said, “There would be extremely many, Bhagavān. The number of Ganges Rivers alone would be countless, let alone their grains of sand.” “Subhūti, I will now tell you a truth. If a good man or good woman filled such a number of three thousand great thousand-worlds with the Seven Precious Jewels in the practice of giving, would he or she obtain many merits?” Subhūti said, “Extremely many, Bhagavān.” The Buddha told Subhūti, “Just so, if good men and good women accept and maintain even a four-line gāthā from within this sūtra, speaking it to others, then the merits of this surpass the former merits.

Section 12: Venerating the true teachings

“Moreover, Subhūti, if one speaks even a four-line gāthā from within this sūtra, you should understand that this place is like the shrine of a buddha. In every world, the devas [nobles or holy people], humans, and asuras [outcasts or base people] should provide offerings to it. How much more so for those capable of accepting and maintaining the entire sūtra? Subhūti, you should know that this is a person with the highest and most exceptional Dharma. Wherever this sūtra dwells is the Buddha or an honored disciple.”

Section 13: Receiving and maintaining the Dharma

Subhūti asked the Buddha, “Bhagavān, by what name should we revere and maintain this sūtra?” The Buddha told Subhūti, “This sūtra is called the Vajracchedikā Prajñāpāramitā, and by this name you should revere and maintain it. Why is it called this? Subhūti, this Prajñāpāramitā spoken by the Buddha is not a perfection of prajñā. Subhūti, what do you think? Has the Tathāgata actually spoken any dharma?” Subhūti replied, “Bhagavān, the Tathāgata has not spoken.” “Subhūti, what do you think? Are there very many atoms contained in three thousand great thousand-worlds?” Subhūti replied, “There are extremely many, Bhagavān.” “Subhūti, the atoms spoken of by the Tathāgata are not atoms, and are thus called atoms. The worlds spoken of by the Tathāgata are not worlds, and are thus called worlds. Subhūti, what do you think? Can the Tathāgata be seen by means of the Thirty-two Marks?” “No, Bhagavān, the Tathāgata cannot be seen by means of the Thirty-two Marks. Why? The Thirty-two Marks that the Tathāgata speaks of are not marks, and are thus called the Thirty-two Marks.” “Subhūti, suppose there were a good man or good woman who, in the practice of giving, gave his or her body away as many times as there are sand grains in the Ganges River. If there are people who accept and maintain even a four-line gāthā from within this sūtra, then the merits of this are far greater.”

Section 14: Leaving appearances: Nirvāṇa

At that time, Subhūti, hearing this sūtra being spoken, had a profound understanding of its essential meaning, and burst into tears. He then addressed the Buddha, saying, “How exceptional, Bhagavān, is the Buddha who thus speaks this profound sūtra! Since attaining the Eye of Prajñā, I have never heard such a sūtra! Bhagavān, if there are again people who are able to hear this sūtra thusly, with a mind of clean and clear belief, giving rise to the true appearance, then this is a person with the most extraordinary merits. Bhagavān, the true appearance is not an appearance, and for this reason the Tathāgata speaks of a true appearance.

“Bhagavān, being able to hear this sūtra thusly, I do not find it difficult to believe, understand, accept, and maintain it. However, in the next era, five hundred years from now, if there are sentient beings who are able to hear this sūtra and believe, understand, accept, and maintain it, then they will be most extraordinary. Why? This is because such a person has no notions of a self, notions of a person, notions of a being, or notions of a life. Why? The appearance of a self is not a true appearance; appearances of a person, a being, and a life, are also not true appearances; those who have departed from all appearances are called buddhas.”

The Buddha told Subhūti, “Thusly, thusly! If there are again people who are able to hear this sūtra, and are not startled, terrified, or fearful, know that the existence of such a person is extremely rare. Why? Subhūti, this foremost pāramitā that the Tathāgata speaks of is not a foremost pāramitā, and is thus called the foremost pāramitā.

“Subhūti, the Pāramitā of Forbearance that the Tathāgata speaks of is not a pāramitā of forbearance. Why? Subhūti, this is like in the past when my body was cut apart by the Kalirāja: there were no notions of a self, notions of a person, notions of a being, or notions of a life. In the past, when I was being hacked limb from limb, if there were notions of a self, notions of a person, notions of a being, or notions of a life, then I would have responded with hatred and anger. Remember also that I was the Ṛṣi [‘Sage’] of Forbearance for five hundred lifetimes in the past. Over so many lifetimes there were no notions of a self, notions of a person, notions of a being, or notions of a life.

“Therefore, Subhūti, bodhisattvas should depart from all appearances in order to develop the mind of Anuttarā Samyaksaṃbodhi. They should give rise to a mind which does not dwell in form; they should give rise to a mind which does not dwell in sounds, scents, tastes, sensations, or dharmas; they should give rise to a mind which does not dwell. If anything dwells in the mind, one should not dwell in it, and for this reason the Buddha says that the minds of bodhisattvas should not dwell in form when practicing giving. Subhūti, bodhisattvas should give thusly because it benefits all sentient beings. The Tathāgata teaches that all characteristics are not characteristics, and all sentient beings are not sentient beings. Subhūti, the Tathāgata is one who speaks what is true, one who speaks what is real, one who speaks what is thus, and is not a deceiver or one who speaks to the contrary.

“Subhūti, the Dharma [teachings] attained by the Tathāgata is neither substantial nor void. Subhūti, if the mind of a bodhisattva dwells in dharmas [rules] when practicing giving, then this is like a person in darkness who is unable to see anything. However, if the mind of a bodhisattva does not dwell in dharmas when practicing giving, then this is like a person who is able to see, for whom sunlight clearly illuminates the perception of various forms. Subhūti, in the next era, if there are good men or good women capable of accepting, maintaining, studying, and reciting this sūtra, then the Tathāgata by means of his buddha-wisdom [enlightenment] is always aware of them and always sees them. These people all obtain immeasurable, limitless merit.

Section 15: The merits of maintaining this sūtra

“Subhūti, suppose there were a good man or a good woman who, in the morning, gave his or her body away as many times as there are grains of sand in the Ganges River. In the middle of the day, this person would also give his or her body away as many times as there are grains of sand in the Ganges River. Then in the evening, this person would also give his or her body away as many times as there are grains of sand in the Ganges River. Suppose this giving continued for incalculable billions of eons. If there are people again who hear this sūtra with a mind of belief, without doubt, then the merits of these people surpass the former merits. How much more so for those who write, accept, maintain, study, recite, and explain it?

“Subhūti, to summarize, this sūtra has inconceivable, immeasurable, limitless merit. The Tathāgata speaks it to send forth those in the Great Vehicle, to send forth those in the Supreme Vehicle. If there are people able to accept, maintain, study, recite, and explain this sūtra to others, then the Tathāgata is always aware of them and always sees them. Thusly, these people are carrying the Anuttarā Samyaksaṃbodhi of the Tathāgata. Why? Subhūti, those who are happy with lesser teachings are attached to views of a self, views of a person, views of a being, and views of a life. They cannot hear, accept, maintain, study, recite, and explain it to others. Subhūti, in every place where this sūtra exists, the devas, humans, and asuras from every world should provide offerings. This place is a shrine to which everyone should respectfully make obeisance and circumambulate, adorning its resting place with flowers and incense.

Section 16: Able to purify obstructions

“Moreover, Subhūti, suppose good men and good women accept, maintain, study, and recite this sūtra. If they are treated badly due to karma from a previous life that would make them fall onto evil paths, then from this treatment by others their karma from previous lives will be eliminated in this lifetime, and they will attain Anuttarā Samyaksaṃbodhi. Subhūti, I remember in the past, innumerable, incalculable eons before Dīpaṃkara Buddha, being able to meet 84,000 countless myriads of buddhas, and providing offerings to honor them all without exception. Suppose someone in the next era is able to accept, maintain, study, and recite this sūtra. The merits of my offerings to all those buddhas are, in comparison to the merits of this person, not even one hundredth as good. They are so vastly inferior that a comparison cannot be made. Subhūti, if there are good men and good women in the next era who accept, maintain, study, and recite this sūtra, and I were to fully explain all the merits attained, the minds of those listening could go mad with confusion, full of doubt and disbelief. Subhūti, understand that just as the meaning of this sūtra is inconceivable, its rewards of karma [good deeds] are also inconceivable.”

Section 17: Ultimately without self

At that time, Subhūti addressed the Buddha, saying, “Bhagavān, when good men and good women develop the mind of Anuttarā Samyaksaṃbodhi, how should their minds dwell? How should they pacify their minds?” The Buddha told Subhūti, “Good men and good women develop Anuttarā Samyaksaṃbodhi by giving rise to a mind thusly: ‘I will liberate all sentient beings. Yet when all sentient beings have been liberated, then truly not even a single sentient being has been liberated.’ Why? Subhūti, a bodhisattva who has a notion of a self, a notion of a person, a notion of a being, or a notion of a life, is not a bodhisattva. Why is this so? Subhūti, there is actually no dharma of one who develops Anuttarā Samyaksaṃbodhi.

“What do you think? When the Tathāgata was with Dīpaṃkara Buddha, was there any dharma of the attainment of Anuttarā Samyaksaṃbodhi?” “No, Bhagavān, and thus do I explain the actual meaning of the Buddha’s teachings: when the Buddha was with Dīpaṃkara Buddha, there was truly no dharma of the attainment of Anuttarā Samyaksaṃbodhi.” The Buddha said, “Thusly, thusly, Subhūti! There was no dharma of the Tathāgata’s attainment of Anuttarā Samyaksaṃbodhi. Subhūti, if there were a dharma of the Tathāgata’s attainment of Anuttarā Samyaksaṃbodhi, then Dīpaṃkara Buddha would not have given me the prediction, ‘In the next era you will become a buddha named Śākyamuni.’ It is because there was no dharma of the attainment of Anuttarā Samyaksaṃbodhi, that Dīpaṃkara Buddha gave me this prediction by saying, ‘In the next era you will become a buddha named Śākyamuni.’ Why? ‘Tathāgata’ denotes the suchness of dharmas. Subhūti, if someone says, ‘The Tathāgata has attained Anuttarā Samyaksaṃbodhi,’ there is no dharma of a buddha’s attainment of Anuttarā Samyaksaṃbodhi.

“Subhūti, the true attainment by the Tathāgata of Anuttarā Samyaksaṃbodhi is neither substantial nor void, and for this reason the Tathāgata says, ‘All dharmas are the Buddha Dharma.’ Subhūti, all dharmas spoken of are actually not all dharmas, and are thus called all dharmas. Subhūti, this is like the body of a person that is tall and great.” Subhūti said, “Bhagavān, the body of a person that the Tathāgata speaks of, tall and great, is not a great body, and is thus called the Great Body.” “Subhūti, for bodhisattvas it is also such as this. If someone says ‘I will liberate and cross over innumerable sentient beings,’ then this is not one to be called a bodhisattva. Why? Subhūti, truly there is no dharma of a bodhisattva, and for this reason the Buddha says, ‘All dharmas are not a self, a person, a being, or a life.’ Subhūti, if a bodhisattva says, ‘I am adorning buddha-lands,’ then this is not one to be called a bodhisattva. Why? The adornments of buddha-lands spoken of by the Tathāgata are not adornments, and are thus called adornments. Subhūti, if a bodhisattva has penetrating realization that dharmas are without self, then the Tathāgata says, ‘This is a true bodhisattva.’

Section 18: Of a single unified perception

“Subhūti, what do you think? Does the Tathāgata have the Physical Eye?” “Thusly, Bhagavān, the Tathāgata has the Physical Eye.” “Subhūti, what do you think? Does the Tathāgata have the Divine Eye?” “Thusly, Bhagavān, the Tathāgata has the Divine Eye.” “Subhūti, what do you think? Does the Tathāgata have the Prajñā Eye?” “Thusly, Bhagavān, the Tathāgata has the Prajñā Eye.” “Subhūti, what do you think? Does the Tathāgata have the Dharma Eye?” “Thusly, Bhagavān, the Tathāgata has the Dharma Eye.” “Subhūti, what do you think? Does the Tathāgata have the Buddha Eye?” “Thusly, Bhagavān, the Tathāgata has the Buddha Eye.” Subhūti, what do you think? Regarding the sand grains of the Ganges River, does the Buddha speak of these grains of sand?” “Thusly, Bhagavān, the Tathāgata speaks of these grains of sand.” “If there were as many Ganges Rivers as there are sand grains in the Ganges River, and there were such buddha world realms as there were sand grains in all those Ganges Rivers, would their number be very many?” “It would be extremely many, Bhagavān.” The Buddha told Subhūti, “Such a number of lands possess a multitude of sentient beings, and their minds are fully known by the Tathāgata. Why? The minds that the Tathāgata speaks of are not minds, and are thus called minds. Why is this so? Subhūti, past mind cannot be grasped, present mind cannot be grasped, and future mind cannot be grasped.

Section 19: Pervading the Dharma Realm

“Subhūti, what do you think? If someone filled three thousand great thousand-worlds with the Seven Precious Jewels, and gave them away in the practice of giving, would this person obtain many merits from such causes and conditions?” “Thusly, Bhagavān, from such causes and conditions, the merits of this person would be extremely many.” “Subhūti, if such merits truly existed, then the Tathāgata would not say that many merits that are obtained. It is from the merits that are unconditioned, that the Tathāgata speaks of obtaining many merits.

Section 20: Leaving form, leaving appearance

“Subhūti, what do you think? Can the Tathāgata be seen by means of the perfected body of form?” “No, Bhagavān, the Tathāgata cannot be seen by means of the perfected body of form. Why? The perfected body of form that the Tathāgata speaks of is itself not a perfected body of form, and is thus called the perfected body of form.” “Subhūti, what do you think? Can the Tathāgata be seen by the perfection of all marks?” “No, Bhagavān, the Tathāgata cannot be seen by the perfection of all marks. Why? The perfection of marks that the Tathāgata speaks of is itself not a perfection, and is thus called the perfection of marks.”

Section 21: No speaking, no dharma to speak

“Subhūti, do not say that it occurs to the Tathāgata, ‘I have a spoken Dharma.’ Do not compose this thought. Why? If someone says ‘The Tathāgata has a spoken Dharma,’ then this is like slandering the Buddha, because my teachings have not been understood. Subhūti, one who speaks the Dharma is unable to speak any dharma, and it is thus called speaking the Dharma.” At that time, Living Wisdom Subhūti addressed the Buddha, saying, “Bhagavān, will there be sentient beings in the next era who will hear this spoken dharma and give rise to a mind of belief?” The Buddha replied, “Subhūti, there will be neither sentient beings nor will there not be sentient beings. Why? Subhūti, the sentient beings that the Tathāgata speaks of are not sentient beings, and are thus called sentient beings.”

Section 22: No dharmas may be grasped

Subhūti asked the Buddha, “Bhagavān, is the Buddha’s attainment of Anuttarā Samyaksaṃbodhi actually without attainment?” “Thusly, thusly, Subhūti. With regard to my Anuttarā Samyaksaṃbodhi, there is not even the slightest dharma of Anuttarā Samyaksaṃbodhi which may be grasped.

Section 23: The virtuous practice of a pure mind

“Moreover, Subhūti, the equality of dharmas that has nothing that is better or worse, is called Anuttarā Samyaksaṃbodhi, and by means of no self, no person, no being, and no life, all pure dharmas are cultivated and Anuttarā Samyaksaṃbodhi is attained. Subhūti, these pure dharmas that the Tathāgata speaks of are not pure dharmas, and are thus called pure dharmas.

Section 24: The merits of prajñā are incomparable

“Subhūti, suppose three thousand great thousand-worlds all contained Sumeru, King of Mountains, and there were mountains such as this of the Seven Precious Jewels, given away by someone in the practice of giving. If a person has only a four-line gāthā from this Prajñāpāramitā sūtra, and accepts, maintains, studies, recites, and speaks it for others, then the merits of the other person are not even one hundredth as good. They are so vastly inferior that the two are incomparable.

Section 25: Transformations are not transformations

“Subhūti, what do you think? You should not say that it occurs to the Tathāgata, ‘I will cross over sentient beings.’ Subhūti, do not compose this thought. Why? Truly there are no sentient beings crossed over by the Tathāgata. If there were sentient beings crossed over by the Tathāgata, then there would be a self, a person, a being, and a life. The existence of a self that the Tathāgata speaks of is not the existence of a self, but ordinary people believe it is a self. Subhūti, an ordinary person that the Tathāgata speaks of is not an ordinary person.

Section 26: The Dharmakāya is without appearance

“Subhūti, what do you think? Can the Tathāgata be observed by means of the Thirty-two Marks?” Subhūti replied, “Thusly, thusly, with the Thirty-two Marks the Tathāgata is to be observed.” The Buddha said, “Subhūti, if the Tathāgata could be observed by means of the Thirty-two Marks, then a cakravartin king would be a tathāgata.” Subhūti addressed the Buddha, saying, “Bhagavān, thus do I explain the meaning of what the Buddha has said. One should not observe the Tathāgata by means of the Thirty-two Marks.” At that time, the Bhagavān spoke a gāthā, saying:

- If one perceives me in forms,

- If one listens for me in sounds,

- This person practices a deviant path

- And cannot see the Tathāgata.

Section 27: No severing, no annihilation

“Subhūti, suppose you think, ‘The Tathāgata has not, from the perfection of characteristics, attained Anuttarā Samyaksaṃbodhi.’ Subhūti, do not compose the thought, ‘The Tathāgata has not, from the perfection of characteristics, attained Anuttarā Samyaksaṃbodhi.’ Subhūti, composing this thought, the one who is developing the mind of Anuttarā Samyaksaṃbodhi is then speaking of the severence and annihilation of dharmas. Do not compose this thought. Why? One who is developing the mind of Anuttarā Samyaksaṃbodhi does not speak of a characteristic of the severence and annihilation of dharmas.

Section 28: Not receiving, not desiring

“Subhūti, suppose a bodhisattva, in the practice of giving, filled as many world realms with the Seven Precious Jewels, as there are grains of sand in the Ganges River. If there is a person with the awareness that all dharmas are without self, and accomplishes their complete endurance, then this is superior, and the merits attained by this bodhisattva surpass those of the previous bodhisattva. Subhūti, the reason for this is that bodhisattvas do not receive merit.” Subhūti addressed the Buddha, saying, “Bhagavān, why do you say that bodhisattvas do not receive merit?” “Subhūti, for bodhisattvas to make merit, they should not greedily wish to acquire it, and therefore it is said that there is no merit received.

Section 29: Power and position destroyed in silence

“Subhūti, if someone says that the Tathāgata comes, goes, sits, or lies down, then this person does not understand the meaning of my teachings. Why? The Tathāgata is one who neither comes nor goes anywhere, and for this reason is called the Tathāgata.

Section 30: The principle of the unity of appearances

“Subhūti, if a good man or good woman disintegrated three thousand great thousand-worlds into atoms, would these atoms be very many in number?” “They would be extremely many, Bhagavān. Why? If this multitude of atoms truly existed, then the Buddha would not speak of a multitude of atoms. Yet the Buddha does speak of a multitude of atoms, and therefore the multitude of atoms spoken of by the Buddha is not a multitude of atoms, and is thus called a multitude of atoms. Bhagavān, the three thousand great thousand-worlds that the Tathāgata speaks of are not worlds, and are thus called worlds. Why? The existence of these worlds is like a single unified appearance. Why? The unified appearance that the Tathāgata speaks of is not a unified appearance, and is thus called the unified appearance.” “Subhūti, one who is of the unified characteristic is unable to speak it, and yet ordinary people greedily wish to acquire it.

Section 31: Unborn knowing and perceiving

“Subhūti, suppose a person says, ‘The Buddha teaches views of a self, a person, a being, and a life.’ Subhūti, what do you think? Does this person understand the meaning of my teachings?” “No, Bhagavān, this person does not understand the meaning of the Tathāgata’s teachings. Why? The views of a self, a person, a being, and a life, that the Bhagavān speaks of, are not views of a self, a person, a being, or a life, and are thus called the views of a self, a person, a being, and a life.” “Subhūti, regarding all dharmas, one who is developing the mind of Anuttarā Samyaksaṃbodhi should thusly know, thusly see, and thusly believe, not giving rise to notions of dharmas. Subhūti, the true characteristic of dharmas is not a characteristic of dharmas, and is thus called the characteristic of dharmas.

Section 32: Transforming the unreal

“Subhūti, suppose someone filled immeasurable, innumerable worlds with the Seven Precious Jewels, and then gave these away in the practice of giving. If a good man or good woman develops the mind of a bodhisattva and maintains this sūtra, even with as little as a four-line gāthā, and accepts, maintains, studies, recites, and explains it to others, then the merits of this surpass the others. How should one explain it? Without grasping at characteristics, in unmoving suchness. For what reason?

- All conditioned dharmas

- Are like dreams, illusions, bubbles, or shadows;

- Like drops of dew, or like flashes of lightning;

- Thusly should they be contemplated.

After the Buddha had spoken this sūtra, then Elder Subhūti along with all the bhikṣus, bhikṣuṇīs [nuns], upāsakas, upāsikās, and the devas, humans, and asuras from every world, heard what the Buddha had said. With great bliss, they believed, accepted, and reverently practiced in accordance.

Appendix — Mantra for the Vajracchedikā Prajñāpāramitā

- namo bhagavatīprajñāpāramitāyai

- oṃ īriti īṣiri śruta viṣaya viṣaya svāhā

[Source of this translation – Taishō Tripiṭaka volume 8, number 235. Translated by Trepiṭaka Kumārajīva in 401 CE, as Jin’gang Bore Boluomi Jing (金剛般若波羅蜜經) as cited from here>>

NOTES

[1] Vajra Cutter Sutra Resource Page on FPMT>> https://fpmt.org/edu-news/vajra-cutter-sutra-resource-page/

[2] Hsing Yun (2012). Four Insights for Finding Fulfillment: A Practical Guide to the Buddha’s Diamond Sūtra. Buddha’s Light Publishing. p. 87. ISBN 978-1-932293-54-8.

[3] Five Things to Know about the Diamond Sutra https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/Five-things-to-know-about-diamond-sutra-worlds-oldest-dated-printed-book-180959052/

[4] Nagatomo, Shigenori (2000). “The Logic of the Diamond Sutra