How important is choosing a tradition in Buddhism? What are the differences between “schools’ in Buddhism? Why are there even differences?

It can be quite perplexing for people new to Buddhism to realize that there are many traditions and teaching lineages in Buddhism — with quite different methods. Or, to use a cliché — all paths to one destination.

For each of the major schools, we ask a simple question “Why practice (school)?” — fill in the blank with the school. It may seem overly simplistic, but some people new to Buddhism may find this helpful.

Buddha taught many methods, paths, and skillful means. It is up to us to choose our path and method — the destination is the same — the other shore, Enlightenment.

Why choose? No one path is right, no path is wrong

We make no recommendations in this feature. Below, each of the headings says “Why choose … ? ” for each tradition. This is just a segue into the type of mind that might be suited to this tradition — but it’s certainly not comprehensive or accurate. Each of us is different.

Read through them all to see if any personally appeal to you. You should know your own mind.

Which path will you walk? All Buddhist paths ultimately lead to one destination.

For each of these traditions, we have a special section with numerous features for each. You’ll find them linked below.

Buddha’s core teaching underlies all traditions

Whether you choose to simply sit, as in Zen, or you fully renounce and become a monk or nun, or you engage in the Pureland practice of chanting the name of the Amitabha Buddha, or you undertake the layered visualizations of Vajrayana — all of these are underpinned by the Buddha’s core teaching.

Shakyamuni Buddha teaching.

In Buddha’s own words, this is:

“I teach only two things. Suffering and end of suffering.” — Buddha

The rest are methods

The rest are methods. Pondering Koan riddles is a method. Renunciation is a method. Mantra is a method. Mindfulness is a method.

There are many ways to end suffering — all taught in the many Suttas, Sutras and Tantras taught by Buddha. Each path has more and more elaborate methods for cutting the so-called ten poisons. But the ten poisons are the same, regardless of path you choose. They are all designed, by Buddha, to help us cut:

- greed (sans lobha)

- hate (dosa)

- delusion (moha)

- conceit (māna)

- wrong views (micchāditthi)

- doubt (vicikicchā)

- torpor (thīnaṃ)

- restlessness (uddhaccaṃ)

- shamelessness (ahirikaṃ)

- recklessness (anottappaṃ)

Cutting these ten, is how we stop suffering.

Two monks walking on a beach in Huahin Thailand. Buddhis developed in most countries around the world, sometimes in different forms. Methods may vary, but all teach the two core things Buddha taught.

2 major doctrinal differences between Theravada and Mahayana

Aside from two major “doctrinal” differences between the elder Theravadan tradition and the Mahayana traditions, the core beliefs, the benefits and the root teachings are the same. Both main traditions and all schools within traditions teach quite diverse methods to cut the poisons (kleshas.) For some, this is quietly sitting in mindful meditation. For others, it is transforming the poisons through visualization. For some, it means withdrawing from lay life. For others, it means embracing lay life.

Why then are there so many traditions? Why, within a tradition are there various lineages? Why does it even matter to a new Buddhist or someone not born into a predominantly Buddhist culture?

Buddhism in Tibet may seem different to other traditions, but at its core, it is ultimately the same. We each choose our tradition based on what appeals to our own minds.

Good questions — with no right or wrong answers

These are all good questions, and in answering them, it’s important to emphasize there is no right and no wrong path. The differences mostly relate to practice methods. Some of us suit one tradition, while others benefit from quite different methods. We also have to be careful not to trigger too virulent a debate — because it is not useful to Buddhist practice to engage in politics or division.

The key “doctrinal” differences define the two major traditions, Theravada and Mahayana. It’s fairly easy to analyze the differences, since Theravadan tradition relies almost solely on the Pali Canon of Suttas, while Mahayana teaches from both Pali Sutta and Sanskrit Sutra.

Anatta — and the 2 major doctrinal differences

The main doctrinal difference is in the interpretation of Anatta. Because one of the goals of Buddhism generally is to defeat “ego” the enlightened understanding is there is no permanent self or soul. That doesn’t mean we don’t exist — it’s conceptual and very profound. It can take a lifetime to understand.

Mahayana takes the concept a little further in Buddha’s later Sutras, with the concept of Shunyata — sometimes translated as Emptiness (although that’s a misleading term) or Oneness. The famous “Form is emptiness, emptiness is form” line is from the Heart Sutra in Mahayana Sutra.

In some forms of Mahayana, the ideal Bodhisattvas are visualized, exemplifying the methods of compassion. Here, is Guan Yin, Bodhsiattva of Compassion, on a lotus.

Bodhisattvas and the big bus

The other main philosophical difference is in the notion of the Bodhisattva. While Metta and Karuna (loving kindness and compassion) are important to both main traditions, Mahayana places much more emphasis on Compassion as a “main” practice. Instead of seeking Enlightenment for ourselves — which is already difficult — we seek Enlightenment so that we can help all others become Enlightened as well. This is the Bodhisattva motivation, found in Mahayana. This does not in any way imply Theravada lacks compassion — only that the goals are different.

The core teachings in Buddhism — the Four Noble Truths, Eightfold Path, Dependent Arising — all are taught in both traditions. Yet, based on these main doctrinal differences, the practices and labels are different, although the end destination is the same.

And, that is only the beginning. Mahayana, in turn, has many divergent traditions, such as Chan or Zen, Pureland, and Vajrayana.

Which path do you follow to Enlightenment? All are safe paths, as all were taught by Buddha.

Where do you start?

Wherever you are now, is a good place to start? Are you studying sutra and the life of the Buddha now? That’s where it’s best to begin. There are no actual major contradictions between the paths, other than the two mentioned. The rest tend to be practice methods, that evolved out of the Buddha’s teaching on “skillful means.”

Until you commit to a tradition, school or teacher, try various methods. Or, if you prefer, simply find a teacher or Sangha you identify with and begin practicing.

You’ll find your own path as you go along. And, no matter what tradition or lineage you eventually “settle into” the key is always going to be practice — study, contemplation and meditation. With regular practice, everything else will fall into place. You’ll also develop an understanding of the differences between traditions organically — by actually experiencing them.

A monk walks around the Shwezigon Paya Pagoda in Myanmar.

Why are there different traditions in Buddhism?

There are different traditions in Buddhism because the teachings of Buddha were meant to be applicable to all people, regardless of their background or culture. The different traditions arose out of the need to adapt the teachings to the different cultures in which Buddhism spread.

The key to understanding the different traditions is always going to be practice — study, contemplation and meditation. With regular practice, everything else will fall into place. You’ll also develop an understanding of the differences between traditions organically — by actually experiencing them.

In Theravadan practice, the lay community help support the renunciate practitioners. Here monks receive alms from the lay practitioners. This is a blessing for the laypeople and food for the monks who often eat only one mid-day meal.

It’s not a popularity contest

If this was a “popularity contest” — which it most certainly is not! — top of mind awareness would depend where you live.

Theravada (Pali, meaning “Way of the Elders) certainly, is the main practice in Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia and Laos. Likely Zen Buddhism and Tibetan Buddhism would have the highest awareness in the “western countries” such as North America and Europe, while Pureland Buddhism might be culturally ubiquitous in many parts of Asia. Zen is almost synonymous with Japan, although it originated as Chan in China. Chinese Buddhism or Han Buddhism (simplified Chinese: 汉传佛教; traditional Chinese: 漢傳佛教; pinyin: Hànchuán Fójiào) is the form of Mahayana Buddhism that influenced most of Chinese culture (together with Daoism and Confucianism) including art, literature, philosophy and even medicine.

A Zen garden is synomous with Zen Buddhism. Here is a lovely Zen garden in Ginkakuji Temple in Kyoto Japan.

Cultural Roots of the Traditions

Of course, all traditions have their source roots in Buddha, who was born in what is today Nepal and taught largely in India. The teachings spread throughout Asia.

Theravada Buddhism (Way of the Elders) is the earliest form of Buddhism and is still practiced today in Sri Lanka, Myanmar (Burma), Thailand, Cambodia, and Laos.

Mahayana Buddhism is the form of Buddhism that developed in India and spread throughout East Asia, including China, Japan, Korea, Tibet, and Vietnam.

Vajrayana Buddhism (Diamond Vehicle or Thunderbolt Vehicle) is a tradition within Mahayana Buddhism that developed in India and spread to Tibet, Mongolia, China, Japan, and Korea. Vajrayana is also known as Tantric Buddhism or Tibetan Buddhism, but Vajrayana is the most accurate. (Tantra is simply a word, describing a yogic method, and Tibetan Buddhism is really a niche within Vajrayana.)

A Theravadan monk crossing a suspension bridge in mae Hong Son.

Why choose Theravadan Buddhism?

Why, then, would a student embrace the Theravadan Buddhist path, the Elder Path?

Theravada will appeal to someone who is ready to renounce lay living as a solution to the ten poisons. It will appeal to anyone looking for the earliest core teachings of Buddha. Theravada can appeal to anyone and everyone — you can embrace more than one path! — but it does emphasize renunciation and monastic practice more strongly than others.

The Theravada tradition is the oldest of the Buddhist traditions and embraces the most ancient teachings of the Buddha. Theravadan Buddhism is profound and beautiful.

The Theravada tradition has a strong emphasis on monasticism and renunciation and is therefore well suited for those who are looking to devote their lives to the practice of Buddhism.

Lay practitioners certainly practice, although it is usually in support of monastic activities.

A Mahayana temple during lunar new year.

Why choose Mahayana Buddhism?

Why would a student choose Mahayana Buddhism, the so-called Greater Vehicle — labeled in this way not to be derogatory, but to imply you need a big vehicle to carry all beings to enlightenment?

Mahayana will appeal to someone who is fully engaged in lay life — although there is a very large monastic community in Mahayana. Mahayana will appeal to people who value compassionate activities in the world. It will certainly appeal to people looking for specialized ways to approach Buddhism — since there are many diverse traditions within the giant Mahayana vehicle.

Mahayana Buddhists believe that all beings have the potential to become Buddhas, and they focus their efforts on helping others to achieve this goal. This is the doctrine of Buddha Nature, which is a major, fundamental underpinning of Mahayana.

Mahayana Buddhism is more readily practiced by people not ready to give up lay life, but who want to practice deeply, yet without monastic vows.

Incense is ubiquitous in most major religions worldwide. You cannot enter a Buddhist temple without walking through wafts of pleasant incense smoke. Shown: incense prayer sticks in Thien Hau Pagoda Hochi Minh Vietnam.

Why choose Zen or Chan Buddhism?

The word “Zen” comes from the Chinese word “Chan”, which in turn comes from the Sanskrit word “Dhyana”, meaning “meditation”.

Zen is sometimes described as a “methodless method.”

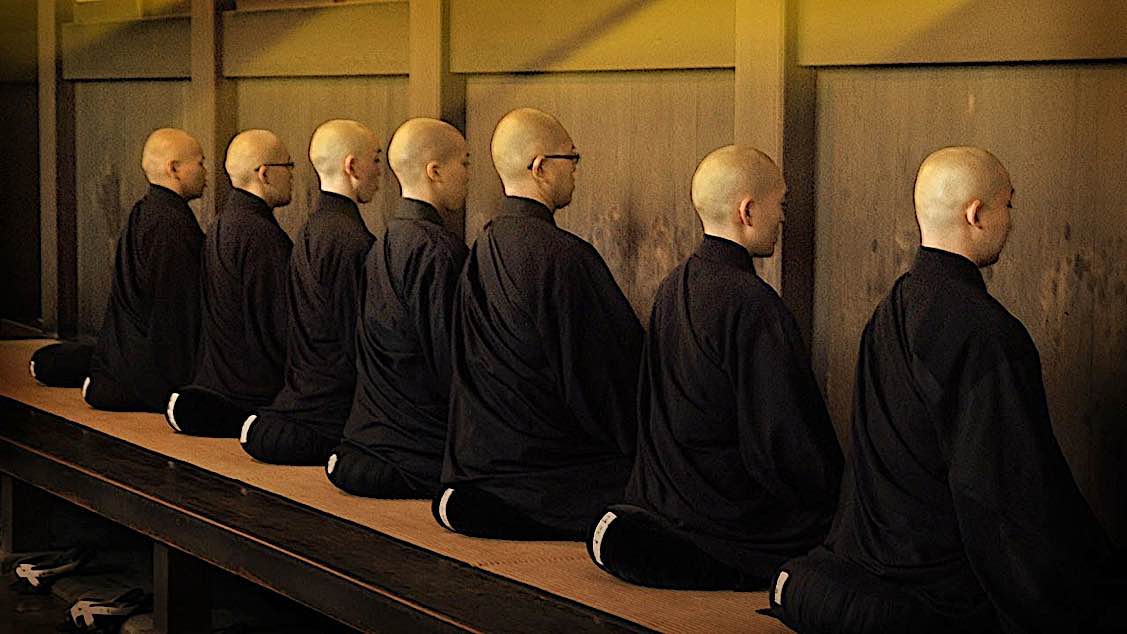

Zen will appeal to anyone looking for direct methods, insight methods and breakthroughs in practice. The many unique methods of Zen — from koans, to Zazen to martial arts disciplines — appeal to disciplined minds or people who aspire to the model of discipline. Oddly, this sense of discipline is provocatively justopoisioned agains the idea of “no method.” Every speck of dust on the pristinely swept floor becomes important.

International renowned Zen Master Thich Nhat Hanh leads walking meditation at the Mahabodhi Temple in Bodhgaya India.

Zen Buddhism, or Chan as it is called in Chinese, is the school that emphasizes direct experience of reality, often expressed in the form of paradoxical phrases known as koans. Zen also depends heavily on Zazen — or just sitting in meditation, often focused on breath, and certainly on mindfulness. The core focus of Zen is on meditation, with the goal of achieving enlightenment through “seeing into one’s own nature”. This can be done through sitting meditation (zazen), as well as other activities such as tea ceremony, calligraphy, and so on. Reciting sutras is another meditative practice.

Zazen, silent sitting meditation — classically, facing a blank wall — is, to some people synonymous with Zen.

Zen is probably the best-known form of Buddhism in the West, and has had a profound impact on Western culture.

Zen is sometimes seen as emotionless, but this is a misunderstanding. The focus on direct experience means that emotions are not suppressed, but rather acknowledged and worked with.

Zen is also a very practical path, and its followers believe that enlightenment can be achieved through ordinary activities such as eating and working and working.

Celebrating Amitabha with chanting in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam.

Why choose Pureland Buddhism?

Pure Land is one of the most popular forms of Buddhism, especially in East Asia. It developed out of Mahayana Buddhism, and has heavy emphasis on Amitabha Buddha and his Pure Land (Western Paradise).

Pureland Buddhism would appeal to someone seeking a very straightforward practice that engages the mind with a single focus combined with devotion for the Enlightened Buddha. It is a devotional path, but also a mindfulness practice.

Pureland Buddhism is based on the teachings of the Buddha Amitabha, who promised to salvation to all who called on his name. This path is therefore sometimes known as “The Buddha of Infinite Light.”

The Pureland tradition is very popular in East Asia, and is especially strong in China, Japan, and Korea.

Amitabha in his pureland in the Chinese style.

This path is often seen as the “easiest” of the Buddhist paths, as it does not require strict renunciation. What is needed is faith in Amitabha and a sincere desire to be reborn in his Pureland. Faith in this context is not blind faith, but is based on Sutra teachings.

Another way to view Pureland Buddhism is that it is one of the easiest ways to focus your mind. All Buddhist methods include various forms of mindfulness — mindfulness of breath, mindfulness of mind, and so on — but with some forms of Pureland (not all forms) the practice is to remain mindful of Amitabha’s name. Simply chanting “Namo Amituofo” becomes a mindfulness practice. Its simplicity is also its power.

This practice is considered to be very accessible and can be done by people from all walks of life.

Tibetan White Pagoda nestled in mountains in nature at Qinghai Lake. Pagodas and Buddhist temples are often integrated beautifully into nature and mountain. Buddhism has always had a close relationship with nature. Buddha found enlightenment under a tree, and spent most of his life in the forests and jungles meditating and teaching.

Why choose Vajrayana Buddhism?

What would lead a student to the Vajrayana, or Diamond Vehicle? As the name implies it is the hardest path to follow, but — like a diamond — it is nearly indestructible. It is also — for those suited to the practice — the most direct path to enlightenment.

Vajrayana Buddhism might appeal to you if you have a logical mind that appreciates methods, stages, steps and discipline — and will suit those who want to measure progress and see fast results. In other words, someone who likes maps. It can also appeal to someone seeking the esoteric or even exotic, due to its deep traditions and colorful practices — but at its core it is a highly structured and details-oriented path.

Vajrayana Tibetan Buddhism in particular places emphasis on the foundations — including education and debate. Here, monks participate in formal debate as part of monastic training.

The map mentioned above is the Vajrayana Sadhana. One of the reasons Vajrayana appeals strongly to logical and disciplined practitioners is its structure, especially it’s formulated Sadhana guided meditations. Some non-practitioners think of Vajrayana as “ritualistic” but what is perceived as a ritual, is actually structured meditations in stages on the path, expressed in Sadhanas.

Sadhanas are not really “ritual” but are more guided meditations. Nothing is ever “left out” because the path is highly structured.

Each sadhana includes elements of refuge, Bodhichitta motivation, seven limbs of practice, offerings for merit, purification, and visualization. Nothing is ever “missing” even in the shortest session.

Prayer flags are ubiquitous in the Himalayas. Printed on them are usually a Windhorse, surrounded by the four auspicious ones — Garuda, Dragon, Tiger, Snow Lion — with prayers and mantras. The wind carries the blessing to world. For a feature on the Four Auspicious Ones, see>>

What about Mantrayana and others?

Within Vajrayana, you have various lineages and also niche practices, such as “Mantrayana” which uses mantra as a focus of mindful practice. Mantrayana is not really synonymous with Vajrayana — it’s simply part of the whole.

Spinning the giant prayer wheels, filled with hundreds of thousands of mantras each is a daily practice for many. Here, a devotee -meditator spins the wheels at Labrang Monastery, Tibet.

There are also several main schools and lineages in Tibet, although these are more differentiated by the lineage of gurus and great teachers — and some methods — but not by core doctrines. These are:

- Nyingma (c 8th century)

- Kagyu (c 11th century)

- Sakya (c 1073)

- Gelug (c 1409)

Commitments in Vajrayana

Vajrayana practitioners take on additional vows and commitments beyond the basic Mahayana vows — as part of that “map” we mentioned — and they also practice visualizations and sadhanas and engage in meditation practices that are unique to Vajrayana — such as Tonglen, Chod and so on. The underpinnings are certainly Mahayana, but with much more emphasis on visualization and transformation and mapped methods that are proven through a lineage of practitioners.

Chod practice by many monks. This active form of practice drumming is an advanced practice, combining activities with chanting mantras and visualizations.

The focus of Vajrayana is on the transformation of the body and mind, with the goal of achieving Buddhahood in this lifetime. This is a tall order, which is why it is considered a “vehicle” rather than a “path”.

Vajrayana practitioners almost always seek out a teacher — lama or guru — to help them navigate the complex teachings and practices. Vajrayana is not undertaken lightly, or casually, but the rapid progress on the path can be extraordinary for those who are suited to this path.

Monks chant mantras, a Mantrayana practice.

What about Tibetan Buddhism?

Tibetan Buddhism is a form of Vajrayana (which originated in India).

The Tibetan Buddhist tradition combines aspects of both Mahayana and Theravada Buddhism, and also draws heavily from the indigenous Bon religion of Tibet, especially in terms of symbols and visualizations — not in terms of core doctrines, which remain Vajrayana Buddhist.

Tibetan Buddhism places a strong emphasis on tantric practices, which are rituals and techniques designed to speed up the process of achieving Buddhahood, largely through visualization.

Buddhist Vajrayana meditation often includes sounds, actions, and repetitive mantras — all very powerful ways to “empty” the mind and “nonfocus” the monkey mind.

Why choose Shingon Vajrayana Buddhism?

Shingon is one of the major schools of Buddhism in Japan — and is one of the few surviving lineages of Vajrayana.

Shingon might appeal to you in the same way as Vajrayana, if you tend towards the exotic, esoteric, or you like a solid road map to Enlightenment.

It originally spread from India to China through monks such as Vajrabodhi and Amoghavajra. This developed as Tangmi in the Tang Dynasty of Chian, and later came to flourish in Japan under a Buddhist monk name Kukai.

Shingon monk at Mount Koya Wakayama Prefecture Osaka.

The name “Shingon” means “true word” translated fromt he Chinese Word 真言 (zhēnyán) which in turn is the Chinese transliteration of the Sanskrit word Mantra.

The focus of Shingon is on the use of mantras and mudras (ritual hand gestures) to achieve Buddhahood in this lifetime. The practices are considered to be very powerful and are only taught to advanced students.

This is just the “tip” of the iceberg, since there are many Japanese schools of Buddhism.

Vibrant red Konpon Daito Pagoda in the Unesco-listed Danjo Garan Shingon Buddhist complex Koyasa Japan.

Why choose Nichiren Buddhism?

Nichiren also is very popular in the west, made famous through the teachings of Nichiren with its focus on the Lotus Sutra as the main sutra of practice.

Nichiren may appeal to you if you like a very precise and uncomplicated method of practice and certainly if you embrace the Lotus Sutra as the ultimate teaching of the Buddha. The Lotus Sutra is a very profound Sutra, of many chapters, and covers all of the teachings of Buddha.

A statue of Nichiren at Myoren-ji Temple in Kamigyo.

Nichiren was a 13th-century Japanese Buddhist monk who had a great impact on Japanese society.

The focus of Nichiren is on the chanting of Nam-myoho-renge-kyo as the main practice, which is the title of the Lotus Sutra. The goal is to achieve Buddhahood in this life through this practice.

Nichiren Buddhist Temple Monobusan Kuonji Monobu, Japan.

Other Japanese Schools

There are several schools and traditions in Japan, including the Six Nara Schools: Hosso, Kusha, Shanron, Jojitsu, Kegon and Risshu.

There are the more esoteric schools, such as Tendai, Shingon (mentioned above), and Shugendo.

The newer schools are the Jodo-shu (Pure Land school), Yuzu-Embutsu, Jodo Shinshu (True Pure Land), Soto school of Zen (famously founded by Dogen), — with heavy focus on Lotus Sutra), Ji-shu, Fuke-shu, Shingon-risshu, Obaku, and Sanbo Kyodan.

The Swayambhunath monastery in Kathmandu, Nepal.

So, what’s the bottom line?

The bottom line is that there is no one right path. The path you choose should be the one that feels right for you. There are many different traditions within Buddhism, and each has its own unique flavor. Try out a few different ones to see which resonates best with you. And remember, the most important thing is to practice regularly and with an open heart.

Choose a path that will support your practice, not hinder it. With diligent effort, any of these paths can lead to enlightenment — but not all them are suited to every mind.

You know your own mind. Choose the tradition or path that appeals to your mind. And don’t forget, you can always try out another one later if you find that your needs have changed. Life is a journey, after all. Why not explore?