Sadhanas are not just sacred Dharma texts, held up as venerable sacred texts — in Vajrayana they are (metaphorically) the recipes to successful Buddhist realizations.

As with a chef in the kitchen, you don’t have to use the recipe — but it ensures a good result. The spectacular result, as with fine cuisine, is due to a preceding lineage of accomplished practitioners (metaphor: teaching chefs), unbroken teaching lineage going back to the source of wisdom, the Buddha.

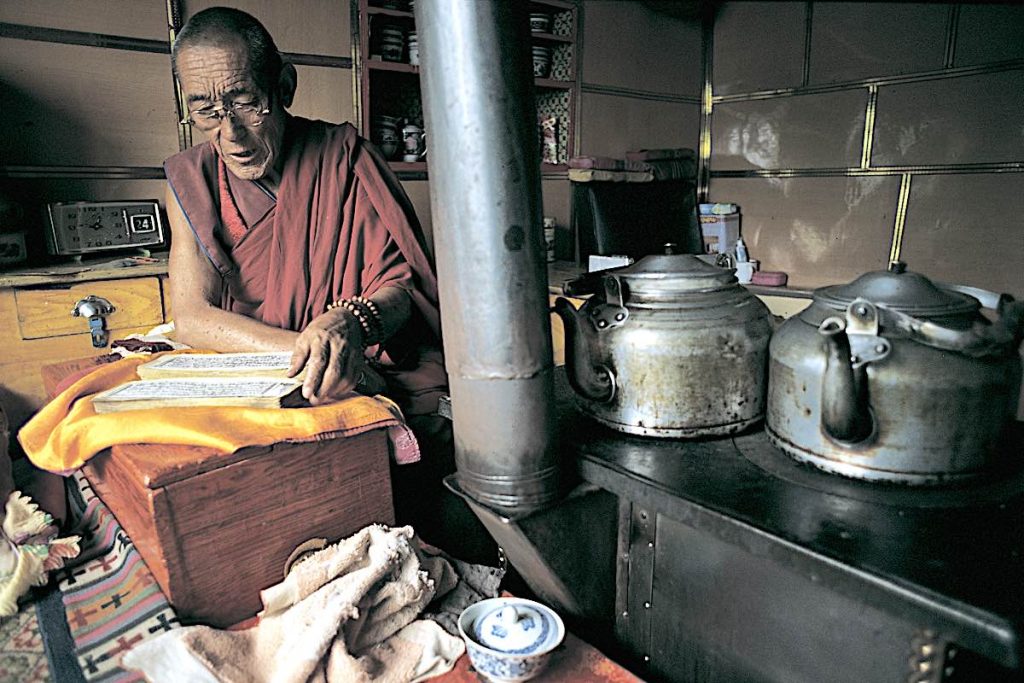

No matter where you are, the Sadhana is your guide. Here a very experience monk practices in a tiny apartment. You can practice anywhere, with a proper mindset, but the Sadhana text is indispensible. It’s not only a recipe for “how to practice” it’s a sacred Dharma text.

Yes, there is more to a successful “dish” than the recipe: there’s the technique (meditation practice), secret methods (expert instruction), and diligence (it can take a hundred tries to perfect a special dish.) (Choose your metaphor: actor with a “script”, pianist with sheet music, athlete, scientist. For simplicity I’m using chef.)

Sanskrit Sādhanā or Tibetan sgrub thabs, literally translates as “a means of accomplishing”. The Sanskrit root “Sadh” means “completion.” These should not be confused with “Pujas.” Sadhanas are often the “commitment” practice given by teachers at an empowerment. Today, they are widely available, including digitally, and in many languages.

What is a Sadhana?

Sadhana is a step-by-step guide to practice and meditation. All the elements, with none missing (like a good recipe), are formulated for the student: preparation, purification, guru devotion, visualization, seven-limb practice, and on it goes; even steps you might not comprehend at this time (such as, for example, body mandala.) You can’t miss a step, or do something wrong if you follow the Sadhana handed down through hundreds of years by realized teachers — assuming you have empowerment from that lineage of teachers. Even if you don’t achieve realizations, due to some obstacle, at least you know you’re “doing it right.”

Formal sadhanas are transmitted in text form through an unbroken lineage from guru to guru back to the Buddha. Here, a meditator in lotus position meditates with a written text (Sadhana) as a guide. A Sadhana combines sounds (prayers and mantras), actions (mudras), intense visualizations (guided), even a sense of place (mandalas) and the six senses (smells, tastes, and so on from the visualized offerings.)

By following the Sadhana recipe, daily — practiced as demonstrated by your teacher (chef) — it becomes firmly imprinted on the mindstream. Until actual realizations are achieved, the Sadhana is still the best way to make rapid progress. It ensures proper practice (nothing missing or modified that might alter results) and integrity of method.

Many modern Buddhists groan when they see the length of traditional Sadhanas. While Medicine Buddha Sadhana meditation can be as short as a page or two, some Higher Yoga Tantras come in at dense 100 pages or more. Most have “short” and “long” versions — but given by the teacher, with the understanding that one should practice the long version when possible. As well-known teacher Alexander Berzin explains:

“There will be an abbreviated one; there will be a full one; sometimes there’s a medium level as well. And my teacher Serkong Rinpoche said that the abbreviated forms, the short forms, are for advanced practitioners. It’s the long, full forms that are for the beginners.” [1]

Alexander Berzin (right) greets the Dalai Lama.

Later, in the teaching, he elaborates: “There’s a following thought from that, before I get into the parts of the sadhana. The implication is that we have to really familiarize ourselves with the long one before we can effectively practice the short one. If we only do the short one without knowing the long one, it won’t be very effective because we’re leaving out too much. You don’t really know what is packed into it.”

The reason is simple. Before taking “shortcuts” one has to master the essence.

Monks practicing Sadhana at a retreat at Drepung Monastery Lhasa, Tibet. Sadhanas are ritualized text that helps us learn, but they are also sacred Dharma texts meant to be recited word for word. Even experience practitioners still refer to the text. Out of respect for the lineage, the Dharma and the Three Jewels, we practice as guided by our teacher and our Sadhana.

The three secrets of Tantric Sadhana

Although there are different types of Sadhana, there are three parts to all Sadhanas — also called the three secrets. Venerable Khempo Ringu Tulku explains:

Venerable Khempo Ringu Tulku

“…the three “secrets”, characterise sadhanas, and not only sadhanas, but all Buddhist practices:

In the beginning, or during the preparation phase, there is the secret of Bodhicitta

In the middle, that is the real practice, there is the secret of Selflessness

In the end, there is the secret of Dedication.”[3]

In other words, the first section of a Sadhana focuses on developing Bodhichitta: “I am doing this for the sake of all sentient beings, I am going to deliver them and lead them to Buddhahood”, as Venerable Khempo Ringu explains.

An inside spread of “Tara in the palm of your hand.” There are guided meditations (sadhanas) with illustrations for each of the 21 Taras. Uniquely, in this case, the 21 Taras are in the precious Surya Gupta tradition — where each of the 21 Taras appears different. In other systems, the 21 Taras appear similar, changing only in colour and a few minor expressions. To order the paperback edition of this book, visit Amazon>>

Then, in the middle, we focus on practice without selfishness — with no attachments and “with a view of Shunyata.” To do this, we have to “purify” obscurations, develop merit (through the six paramitas or givings). We also generate ourselves (or pretend to) as the Enlightened Deity as a method to remove those attachments and develop wisdom. Ven. Khempo Ringu elaborates:

“Through the practice of sadhanas, we forcefully turn ourselves into a deity, and we exercise or train to see ourselves, our body, speech and mind, as the body, speech and mind of the Buddhas, even though we have not actually reached that stage. This is what is meant by exercising at the result level, which is why Tantrayana is sometimes called the Yana of Results.”

Thirdly, we dedicate the merit of the practice to the benefit of all sentient beings.

“Emerging from the meditation, when we return to the mundane level of consciousness, we again dedicate whatever merits we may have gained through the practice we have just done for the benefit of all sentient beings, we say the wishing prayers and conclude the sadhana by the Mangalam prayer, which means “auspicious prayer”.

Incessant Sadhana practice and mantra recitation are recommended by Guru Rinpoche.

The secret of Sadhanas

As with recipes, the Sadhana ensures consistency of result. It ensures all the steps are taken, none forgotten, step-by-step, properly and completely. There may be shortcuts for fast-food, but not for a dish people will never forget; for that special dish, guidance from a chef (teacher), a demonstration and guiding hand (empowerment), weeks or months of repetition (practice), and good skills and focus are required.

Sadhanas, depending on whether the student is practicing lower tantra or higher tantra, can be simple or very long and detailed. Not to overuse my analogy, but it’s the difference between a cheese omelette recipe and a soufflé. Even with a cheese omelette, the expert cook with years of practice will make this simple dish irresistible.

The unifying factor of all Sadhanas: motivation

Without proper motivation — the Bodhichitta motivation, specifically — there is no purpose to Mahayana Sadhana. H.E. Zasep Rinpoche explains:

H.E. Venerable Zasep Tulku Rinpoche has taught in the West for 40 years and is spiritual head of Gaden Choling for the West centres in Canada, U.S. and Australia.

“Motivation at the beginning, and dedication at the end. According to Kadam tradition and Gelug tradition, in the Lamrim teachings, mentioned it is very important to have right motivation in the beginning — the beginning of your practice.

Let’s say you sit down to meditate, or do sadhana practice — whatever practice you do — you must, and should, begin with right motivation, pure motivation. That makes a big difference for your practice.

“For instance, when you generate Bodhichitta motivation, pure motivation, you say, from your heart, “I would like to do this practice, meditation session, or sadhana practice, or mantra recitation, for the benefit of all sentient beings. Enlightenment for all sentient beings. May I become Buddha for the sake of all sentient beings, as soon as possible. For that reason, I am going to do Samatha Vipassana meditation, or I would like to do sadhana — say, sadhana of Tara, or sadhana of Avalokiteshvara.”

Preliminary practices included

Most Sadhanas contain preliminary practices — the foundation practices (Ngondro) necessary in Vajrayana practice. In today’s modern age of (mostly) lay practitioners, it is rare to find time to do 100,000 prostrations, 100,000 water bowl offerings, 100,000 Mandala offerings, 100,000 Vajrasattva mantras — all before even beginning practice. Beneficial, certainly, but logistically impossible for many of us.

Fortunately, if you’re unconvinced of the merits of those important foundations, most Sadhana’s include the important ones. So, if you “jump ahead” to deity practices — with the permission of your teacher, of course — at least you can continue to practice the foundations every single day, especially the “four special” Ngondro:

Most complete Sadhanas include all of these, and other preliminaries.

Mandala is usually part of preliminary offerings in many traditional Sadhanas. It is a visualized offering. It is optional to use a mandala set as shown. Often we use our mala coiled in our hands with a mudra to represent the mandala. A traditional mandala set is a “model of the universe” with Mount Meru in the centre — the axis mundi of the cosmos — surrounded by various dimensions and perceptions of the universe. In traditional offerings, these “Universes” are called “continents.” By constructing and offering the mandala of jewels or rice, we make the ultimate offering of the entire visualized universe to our Gurus, the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas, Yidams, and Enlightened Ones.

The ingredients of Sadhana

As with recipes, some Sadhanas have very few ingredients; a secret of many great dishes is very few ingredients. Others, require complexity (analogous to higher tantra.)

The main elements of any Sadhana (such as Medicine Buddha) form the base elements of the more complex Higher Tantras as well:

-

Refuge: taking Refuge in Guru and the Three Jewels: Buddha Dharma and Sangha

-

Generating Bodhichitta (and often meditating on the Four Immeasurable)

-

Seven-Limb Practice (all Sadhanas have either a simple or highly detailed version of this)

-

Generating as deity: Vajrayana is unique in Buddhism; it adds “Generation as a deity” or “visualization” to other forms of meditation (such as breath or mindfulness); specifically, visualization of becoming the Enlightened Being. Although we’re only practicing (or play-acting the Enlightened role) — it is vital role-playing; similar to an actor rehearsing the script, or a chef praticing with ingredients. Importantly, the Sadhana will fully describe in elaborate detail, exactly what to visualize.

-

Mantra recitation: introduces sacred sound to the recipe — this is one of the “secret sauces” of Vajrayana

-

Dedication of the merit (considered indispensable in Buddhist Practice).

The goal: a shortcut to Enlightenment

Vajrayana is called the “lightning path” — the fast path to Enlightenment — because of highly formulated methods proven by the Buddha and realized teachers. Therefore, the ultimate goal of any Sadhana is to provide the “steps” or recipe for Enlightenment. The nearer goal would be to develop compasion, wisdom and realizations. In a teaching on White Tara, Lama Zopa Rinpoche explained the essence:

Lama Zopa Rinpoche

“When Lama Tsongkhapa asked Manjushri: “What is the quick way to achieve enlightenment?” Manjushri advised Lama Tsongkhapa to attempt all these together: purifying the obstacles to attainment (Vajrasattva practice is what is normally mentioned in texts, but it includes Confession of Downfalls with recitation of the Thirty-five Buddhas’ names and so forth); collect the necessary condition of merit (offering mandalas is what is usually mentioned); second (since the previous two are counted together), make one-pointed request to the guru to receive blessings; and third, train your mind in the actual body of the practice, the stages of the path to enlightenment. This is the answer Manjushri gave to Lama Tsongkhapa’s question.” [2]

Of course, Sadhanas contain the essence of this teaching.

Purposes of the steps

Prior to achieving the greater goal, you could distill down the various methods to certain purposes or tactical goals:

-

Purifying negative karma (confession)

-

Generating merit (through offerings and so on)

-

Developing compassion (Bodhichitta practices)

-

Developing wisdom and insights

- Overcoming incorrect perceptions of the nature of reality.

You can also think of Sadhanas as formulas that help us overcome the Three Poisons:

-

Delusion (Sanskrit: moha, Tibetan gti mug, English: confusion, ignorance)

-

Attachment (Sanskrit raga; Tibetan ‘dod chags; English desire, sensuality, greed)

-

Aversion (Sanskrit dvesa, Tibetan zhe sdang; English hatred)

For example, prostrations help us overcome “pride’ which is associated with Attachment to Ego. Visualizing our enemies being blessed (part of many Sadhanas) helps overcome Aversion or hatred. Offerings help us overcome “greed” which is also Attachment. Visualizing the deity and mantra help us develop the wisdom to overcome Delusions.

Monks reading from a Sadhana or Puja text. Sadhanas and Puja texts are a format, a teaching recipe, but also they are part of the lineage, sacred words meant to be recited as passed down (transmitted) by your teacher.

Ingredients of more advanced practices

Almost all longer Sadhanas begin with a description of the lineage. This helps reinforce the “source” of our practice. Alexander Berzin explains:

“Now the structure of a sadhana is – the full sadhanas – is that it starts with a lineage practice. So you visualize the whole lineage going back to the Buddha, in whatever form the Buddha might have appeared in for giving the practice. Whether it’s Vajradhara, whether it’s Samantabhadra, whatever it is, it doesn’t matter. It will be different in each practice. And then you imagine the whole line of lineage masters going all the way down to your present master, the one that you receive the empowerment from, and you recite a verse for each one of them; or it can be a verse that includes a few of them.” [2]

The base sauce really doesn’t change when a student moves to more advanced practices. All recipes have the methods listed above. The key difference as the student advances is the introduction to more complicated methods with more and more sumptuous results. As with any magnificent chef’s dish, these more complicated recipes take years to master — the results are incredible.

The great sage Naropa meditates before his Yidam Vajrayogini. Naropa’s famous teachings are the Six Dharmas of Naropa. These methods are passed down, from teacher to teacher to teacher through the centuries, unchanged in the form we practice today. This is what makes Sadhanas precious and important.

Eleven Yogas of Vajrayogini

The Eleven Yogas of Vajrayogini — for example — contains a highly formulated complete long practice of Highest Yoga Tantra. Other Highest Yoga practices have these ingredients (or most of them) but Vajrayogini is considered the “ideal practice” for the modern age, in part because the map to realizations is so detailed and precise. Although we cannot elaborate on these methods here — you must have the guidance of a teacher — the descriptions of the 11 Yogas are widely published, and simply listed here to give you the context (each has very detailed methods and extensive teachings). Typically, each of these might be the subject of one or more days of teaching as an introduction from the teacher:

-

Yoga of Sleep

-

Yoga of Arising

-

Yoga of Experiencing Nectar

-

Yoga of the Immeasurables

-

Yoga of the Guru

-

Yoga of Generation

-

Yoga of Purifying and Blessing All Living Beings

-

Yoga of Receiving blessings from the Enlightened Ones

-

Yoga of Verbal and Mental Recitation of the Mantra

-

Yoga of Inconceivability

-

Yoga of Daily Activities

As part of these, there are still the Seven Limbs, Offerings (including, in this case, higher offerings such as Tsog and Torma), Purification (requesting Forbearance), auspicious prayers and dedication.

Special ingredients

Some Sadhanas have other special ingredients, such as detailed body mandala. Then, of course, there’s “completion” practice — which normally requires years of practice and expertise and works with the inner channels and winds.

All of these methods, even the simplest, can take a lifetime of effort. By having the “recipe” we make sure no time is wasted with experimentation that either leads nowhere or is detrimental.

By way of analogy, science is built on its precursors. A scientist doesn’t have to re-prove every theory and conduct the same experiments over and over. Science progresses, building on the “backs” of its previous discoveries. Vajrayana, similarly, builds on the insights and wisdom and achievements of its precursors, the great teachers going back to Shakyamuni Buddha.

The habit of Sadhana is about results, not boredom

Many people don’t embrace Sadhana because they feel it’s too repetitive (boring) — like playing the scales on a piano keyboard over and over. Never-the-less, regardless of the expertise we are trying to develop — professional sports, musician, chef, author, engineer or spiritual explorer — we not only need knowledge (teachers); we also need constant repetition and practice with known formulas (recipes) that are proven to lead to conclusive results.

But, why do we have to “speak it?”

Two techniques in education are well-established: verbal and written repetition. It is well established that these lead to absorption and learning. Saying something out loud also “activates” parts of the mind that reading silently does not — including memory recall, activation of visualization elements, and so on.

The great teachers of Buddhist lineage long ago relied on the power of verbal repetition. Many sadhanas were not written down but were verbally transmitted. For convenience, today, we are fortunate to have many of them written, translated and transcribed.

Reading them aloud not only assists in visualization and recall, but it also ensures no steps are missed.

Meditating on the self as deity (in this example as Hayagriva –image from this Hayagriva video>>) is a profound practice — but the practitioner must have permission and empowerment to meditate the self as Hayagriva — otherwise, visualize Hayagriva in front of you.

Why do I have to visualize it that way?

Another big question of beginning students — and sometimes more advanced students — is “why do I have to exactly visualize compassion that way?”

Part of our learning experience is to study these symbols. Our teacher will describe their meaning in our teachings. We might explore them more fully in the written commentaries, and then later in our own meditations.

Typically, after we take empowerment into a practice that interests us, we attend teachings on how to practice. Here, Venerable Zasep Rinpoche is teaching a Mahamudra event at Gaden Choling.

No editing, please

The key element, though, regardless of the symbol, it is important not to suddenly visualize the deity or symbol differently.

For example, because of our own preference, we might visualize Black Mahakala with rippling abs — our vision of athletic power. Yet, in fact, Black Mahakala has a massive belly — symbolic of vast tummo energy. Changing the sex of a deity also would be highly problematic — typically, male deities represent a different concept from the female.

The symbols are all soundly based on thousands of years of archetypes drilled into our deep subconscious — what Jung described as the Collective Unconcious. Changing imagery is considered ineffective, or even detrimental.

A Sadhana text is the most important “sacred” object in your practice. We take refuge in Buddha, Dharma and Sangha in our practice. The Sadhana clearly represents “Dharma” and is therefore sacred. For this reason, and to avoid the dilution of tradition and lineage, we are asked not to change, edit or modify the Sadhanas. It is this “rule” that keeps the lineage teachings pure.

The long and short of Sadhana

In short, Sadhanas are recipes. Once mastered, under the guidance of the teacher, we should see realizations and results. If we don’t follow the “recipes” results are less likely, or even impossible. The recipes are precious — and we are very fortunate to have the wisdom of ancient realized teacher’s not only written but mostly translated into our own languages.