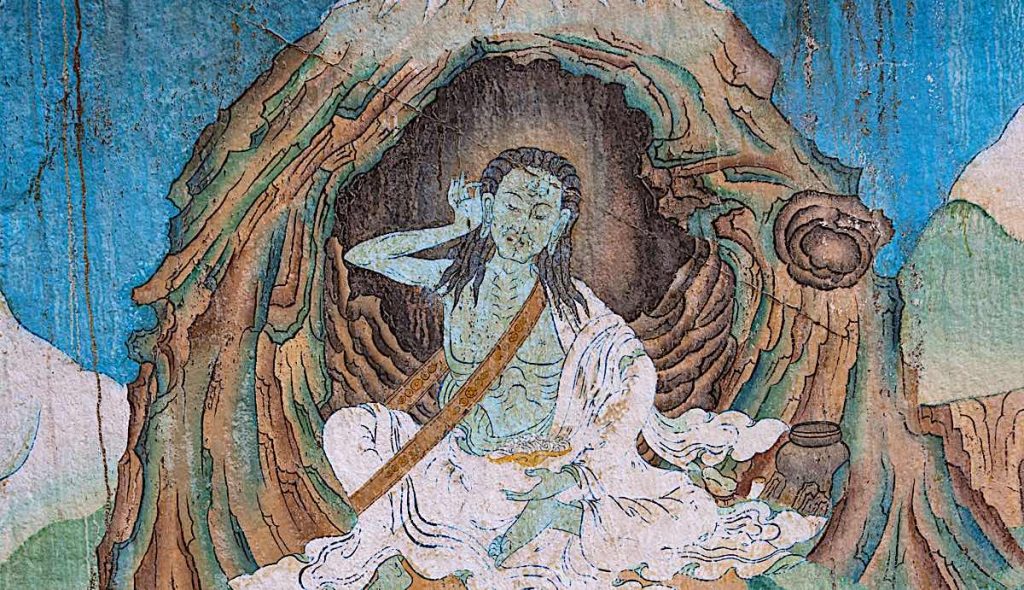

Milarepa (Mi la ras pa in Wylie [Wylie is a method of turning Tibetan script into Roman characters]) was an incredibly wise Tibetan yogi, master, and poet who reached enlightenment in his lifetime. Widely considered to be the founder of the Kagyü school of Tibetan Buddhism. His life story is among the most commonly known and shared narratives in Tibetan culture, not only for its Buddhist profundity but for how interesting, moving, and glorious it is as well.

Milarepa painting, Nepal

There is much to the story of Milarepa — an epic story of grand scope — the essence and beauty of his story remain undiminished by time. With themes of evil and redemption, perseverance, and doing what’s right, Milarepa’s story grips both devout Buddhist and casual readers alike.

The history that came before Milarepa

The dates of the birth and death of Milarepa are notoriously difficult to pinpoint. Milarepa’s most famous biographer, Tsangnyön Heruka (gtsang smyon heruka) said that Milarepa was born in a water dragon year and passed in a wood hare year so his time on Earth was from 1052-1135, but other sources push back the dates by one 12-year cycle to 1040-1123. Whenever exactly he was born or died, Milarepa definitely lived in the eleventh and early-twelfth centuries.

The cave of Milarepa.

In ancient as well as present times, life high up on the Tibetan plateau could never be described as easy; one had to do whatever they could to earn a living and survive. One of Milarepa’s early ancestors was a Nyingma tantric practitioner whose name was Jose (jo sras). He was famous for his exorcism rites and had a sizeable fortune and name for himself. Once, Jose encountered a particularly powerful and fierce spirit, but managed to defeat it. In its defeat the demon cried out, “mila, mila (mi la, mi la)!”, which is an admission of defeat and submission.

As a badge of honor and might, Jose took this submission as his new clan title; and so all of his descendants came to be known by the name “Mila”. He went on to have children and grandchildren. One of his grandchildren, Mila Dorje Sengge (mi la rdo rje seng ge) had a penchant for gambling and ended up losing his family’s fortune.

Very old painting of Milarepa (Himalayan Art.org)

They were forced to find a new life elsewhere, eventually settling in Kyangatsa (skya rnga rtsa), a village close to the modern-day Nepalese border. They managed to regain some wealth through trading, and eventually Dorje Sengge married and had a son, Mila Sherab Gyeltsen (shes rab rgyal mtshan), who in turn also married (a woman named Nyangtsa Kargyen [myang rtsa dkar rgyan]) and had a son who would go on to become Milarepa.

When Sherab Gyeltsen heard of the birth of his child, he was delighted to hear it was a boy and so named him Töpah Gah, which means literally “delightful to hear”. The boy went on to display a beautiful and pleasing voice, and so lived up to his name.

Difficult times, difficult choices

When Töpah Gah turned seven, his father came down with an illness that proved to be fatal. Sherab entrusted his estate including his wife, children, and all his wealth and belongings, to his brother and his brother’s wife, but only until Töpah Gah became an adult, at which time they would all go to him.

Statue of Milarepa in the iconic pose. Monastery in Khatmandu, Nepal.

The uncle and aunt however, decided they would simply take everything for themselves and keep it, without taking care of Töpah Gah and his family. In some accounts, this wasn’t entirely wrong as local marriage customs did dictate that the estate should have rightfully stayed with the brother of the deceased.

Whatever the case, the actions of the uncle and aunt left Sherab’s wife and children poor. With nothing to their name, Töpah Gah, his mother, and his sister were forced to work as servants for his uncle and aunt. Töpah Gah himself wrote about this part of his life as follows:

“Our food was food for dogs, our work was work for donkeys… Forced to toil without rest, our limbs became cracked and raw. With only poor food and clothing, we became pale and emaciated.” [1]

When Töpah Gah came of age, his mother Nyangtsa Kargyen pleaded to her dead husband’s brother and wife to honor his last wishes and give her family what was rightfully theirs. Her pleas fell on deaf ears.

In hysterics, grief, and desperation, she sent Töpah Gah to train in the dark arts so that he might take revenge upon their greedy relatives. In some versions of the story, Töpah Gah pleaded with her not to make him go, hesitated and dissented. She remained adamant that this was the only way forward.

Whatever the case, Töpah Gah did leave, learning black magic under Nubchung Yonten Gyatso (gnubs chung yon tan rgya mtsho), and he did kill his aunt and uncle – however, he also murdered the 35 people who were attending a wedding feast at their house.

When the other villagers threatened to reprise him for his actions, Töpah Gah’s mother insisted he conjure up a hailstorm to destroy their crops and shut them up. He may have accomplished what he set out to do, but in doing so also destroyed much of the surrounding countryside.

It was quiet after that. The villagers realized what a great and terrible sorcerer the once quiet, gentle, and golden-voiced boy had become.

But as Töpah Gah beheld the place he called home and the people that he grew up with, he realized the extent of his wrongdoing and the stain that he had put upon the world. He wrote:

“During the day I forgot to eat. If I went out, I wanted to stay in. If I stayed in, I wanted to go out. At night I was so filled with world-weariness and renunciation that I was unable to sleep.” [2]

Another statue in the cave in Marshyangdi river valley Nepal.

The path out of darkness

Töpah Gah came to be certain that the Buddhist path was his only way out of the deep suffering he was experiencing, so he set out to find a master to teach him. The first guru he met decided that Töpah Gah was far too complex and troubled, and so would prove too difficult a student for him. No, who this boy needed was Marpa the Translator, and so Töpah Gah set out to find Marpa.

Marpa Chokyi Lodro (mar pa chos kyi blo gros) was a great translator who lived in Lhodrak (lho brag) in Southern Tibet, and was famous for his fierce temper.

The Great Marpa the Translator.

Töpah Gah reached Lhodrak after some time and met a plowman standing in his field. This was actually Marpa, who had a vision that Töpah Gah would become his most fervent and outstanding disciple and therefore wanted to meet him in a disguise first.

Marpa didn’t immediately teach Töpah Gah anything, instead showering him with relentless verbal and even physical abuse. Töpah Gah was subjected to a number of ordeals and trials, one of which had him construct a massive stone tower, only to tear it down and start over – three times. However, when he built the tower for a fourth time he did not have to tear it down, and that tower of stones that Töpah Gah built still stands in the center of Sekhar Gutok Monastery today.

Milarepa, the singing yogi.

The training that Marpa gave Töpah Gah pushed him to his utmost emotional and physical limits. Whenever Töpah Gah asked for dharmic teachings, his teacher would berate and often even beat him.

In time, but only when Töpah Gah’s desperation had reached its absolute peak, Marpa revealed to Töpah Gah that Marpa’s own master, the great Indian master Nāropa, had prophesied Töpah Gah’s coming to him. He also told Töpah Gah that these trials and hardships were a means of penance for Töpah Gah’s terrible actions and sins.

Years of solitude and meditation

After this, Marpa began teaching Töpah Gah more formally. He started with the lay and bodhisattva vows, and gave Töpah Gah the name Dorje Gyeltsen (rdo rje rgyal mtshan). Dorje Gyeltsen received many tantric instructions that Marpa himself learned in India, and was thereafter commanded to spend the rest of his life meditating in solitary mountain retreats.

Dorje Gyeltsen wanted terribly to do so, but not before returning to his homeland for a short time. After so many years he longed to see his mother again, but when he arrived he found his house in ruins and his mother … dead.

A translation of The Life of Milarepa (by Shambhala Publications, 1977) reads:

“Then I walked across the doorstep and found a heap of rags caked with dirt over which many weeds had grown. When I gathered them up, a number of human bones, bleached white, slipped out. When I realized they were the bones of my mother, I was so overcome with grief that I could hardly stand it. I could not think, I could not speak, and an overwhelming sense of longing and sadness swept over me… But at that moment I remembered my lama’s oral instructions. I then blended my mother’s consciousness with my mind and the wisdom mind of the Kagyu lamas… I saw the true possibility of liberating both my mother and my father from life’s round.” [3]

At this point, Dorje Gyeltsen realized the impermanence of life. It was a profound realization that impacted him deeply, and it served as the final push he needed to begin his mountainous retreats.

Milarepa

The most famous of his retreats is one called Drakar Taso (brag dkar rta so), where he stayed for many years eating nothing but wild nettles. He was there for so long that his clothes turned to tattered rags and his bones stuck out of his skin. It’s said that because he ate only wild nettles, his skin turned green. During this time, some starving hunters stumbled upon him and thought him a ghost, until he spoke to them and taught them about happiness.

It was this period of meditation that gave Dorje Gyeltsen the name we all know him by: Milarepa, meaning Mila the cotton-clad, due to the rags he wore.

Milarepa wrote many poems and songs that remain great treasures of Tibetan literature during his retreats and meditative periods. Milarepa mastered the Mahamudra teachings and obtained great enlightenment. He never actively sought out students; instead, students found him and he sang and taught them many great wisdoms.

The poems and songs of Milarepa

The sutras, a genre of ancient Indian texts found not just in Buddhism but Hinduism and Jainism as well, tell of how the disciples of the Buddha would sometimes come up with verses spontaneously during his lessons.

A number of Buddhist traditions have emulated this but perhaps none more particularly than the Tibetan Vajrayana tradition.

The spontaneous creation of these devotional songs is called nyams mgur in Tibetan.

These songs are modelled after those of Indian tantric practitioners, who wrote songs in the sixth-century songs known as mahasiddhas. The nyams mgur describe both the secret practices of Vajrayana as well as realizations by means of both complex symbolism and allegories.

Tibetan translators such as Milarepa’s master Marpa himself (hence his title, the great translator) brought this custom of composing nyams mgur back to Tibet, among other tantric teachings.

Milarepa is well-known as The Singing Sage. A combination of factors, such as his master Marpa being one of the greatest

Tibetan translators and inheriting the lineage of tantric practices originating in India, combined to make Milarepa a prolific composer of these nyams mgur. His talent, wisdom, golden voice, honesty and humility attracted crowds of people to listen to his musical teachings.

Tsangnyön Heruka was the one responsible for the compilation and arrangement of Milarepa’s most well-known songs four hundred years after he had passed away.

Garma C.C. Chang translated this book, in English called The Hundred Thousand Songs of Milarepa, in 1999. It serves as a biography of Milarepa’s life, a collection of gripping fairy tales and Tibetan folklore, and an insight into Tibetan Buddhism.

A newer translation of the book was published in 2017, by Christopher Stagg.

The cave where the great Mahasidda Milarepa spent years in solitary meditation.

A song about the decision to live in solitude

When Milarepa visited his homeland before his mountainous retreats, he had never thought to find his mother dead. This excerpt of one of his earliest songs shows the depth of his grief, the poignancy of the situation, and the realization that his life had changed forever.

This was a truly pivotal moment in Milarepa’s life. We see him reconcile the life he once knew with the life he now leads as well as the life he will lead in the future. It is worded simply enough, and yet the extent of his emotions is felt astoundingly.

I bow down at the feet of most excellent Marpa.

Bless this beggar to turn from clinging to things.Alas. Alas. Ay me. Ay me. How sad.

People invested in things of life’s round—

I reflect and reflect and again and again I despair.

They engage and engage and stir up from their depths so much torment.

They whirl and they whirl and are cast in the depths of life’s round.Those dragged on by karma, afflicted with anguish like this—

What to do? What to do? There’s no cure but the dharma.

Lord Akṣobhya in essence, Vajradhara,

Bless this beggar to stay in mountain retreat.In the town of impermanence and illusion

A restless visitor to these ruins is afflicted with anguish.

In the environs of Gungtang, a wondrous landscape,

Grasslands that fed yaks, sheep, cattle, and goats

Are nowadays taken over by harmful spirits.

These too are examples of impermanence and illusion,

Examples that call me, a yogin, to practice.This home of four pillars and eight beams

Nowadays resembles a lion’s upper jaw.

The manor of four corners, four walls, and a roof, making nine

These too are examples of impermanence and illusion,

Examples that call me, a yogin, to practice.This fertile field Orma Triangle

Nowadays is a tangle of weeds.

My cousins and family relations

Nowadays rise up as an army of foes.

These too are examples of impermanence and illusion,

Examples that call me, a yogin, to practice.

My good father Mila Shergyal

Nowadays, of him no trace remains.

My mother Nyangtsa Kargyen

Nowadays is a pile of bare bones.

These too are examples of impermanence and illusion,

Examples that call me, a yogin, to practice.My family priest Konchok Lhabüm

Nowadays works as a servant.

The sacred text Ratnakūṭa

Nowadays serves as a nest for vermin and birds.

These too are examples of impermanence and illusion,

Examples that call me, a yogin, to practice.My neighboring uncle Yungyal

Nowadays lives among hostile enemies.

My sister Peta Gonkyi

Has vanished without leaving a trace.

These too are examples of impermanence and illusion,

Examples that call me, a yogin, to practice.Lord Akṣobhya in essence, compassionate one,

Bless this beggar to stay in mountain retreat. [4]

The end of Milarepa’s time in this world

Milarepa’s life changed completely and forever when he left his homeland to retreat to the mountains; he achieved his goal of enlightenment and perfect realization. He went on to win not only the admiration of almost all the people in his land, but their love and faith as well.

However, it was not to last. There were some dharma teachers who were jealous of Milarepa. They saw how people thronged to him and wanted the popularity and adoration that he received for themselves.

One of these teachers, Geshe Tsakpuwa (rtsag phu ba) posed as Milarepa’s student so that he could get close enough to kill him. He conspired to give his master poisoned curds. It is believed that Milarepa knew of this plot all along, but went with it anyway as he felt that it was time for him to pass away at his age (about 84).

There are accounts of Milarepa’s funeral which include many miracles, such as goddesses appearing to carry away his relics, leaving behind only a lump of rock sugar, a knife, some flint steel, a piece of his robe – and of course, his hundred thousand songs.

The sorcerer who became one of the greatest yogins of all time

Milarepa was a boy that grew up in relative wealth and comfort, and then lost everything at a young age. His father’s death didn’t just bring grieving for a lost parent, but it plunged his world into the kind of instability, pain, and suffering that no one should ever have to go through.

He made bad choices and did incredibly bad things. And yet, he changed his ways. He sought out help and did whatever it took to pay for his sins and become a good person again. He went on to not only become beloved by nearly all who came across him but he became a saint as well and continues to inspire, teach, and lead long after his passing.

Milarepa was just a human. His story teaches us that anguish and struggle can come our way, but that with resolve comes triumph. He was nothing but a man who realized his own natural, pre-existing higher self and his untapped wisdom, and who learned how to treat himself and others with compassion.

The Singing Sage invites every ordinary person to recognize their higher selves as well. If even he, a murderer and sorcerer could become a saint by doing nothing but repenting and putting in the work – we can as well.

Sources

[1] [2] [3]

[4]

https://treasuryoflives.org/biographies/view/Milarepa/3178

Other sources

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Milarepa

https://www.learnreligions.com/the-story-of-milarepa-450200

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Songs_of_realization