In Zen-Chan Buddhism, the “Tale of the True Dragon” is used by teachers to illustrate the importance of true practice over entirely intellectual study.

Imagine waking one morning to find a dragon “coiled by [your] bed, its scales and teeth glittering in the moonlight.”[5] Would you scream in terror or embrace the opportunity to learn?

The great teacher Dogen wrote, “I beseech you, noble friends in learning through experience, do not become so accustomed to images that you are dismayed by the true dragon.”[5]

Stepping beyond study — talking to Dragons

Does your study of sutra and Buddha’s teachings take that necessary step beyond intellect into practice? Do your concepts of reality make “belief in dragons” fanciful or allegorical? Are Dragons “True” or symbols? Are symbols any less real for being mythical? Do you embrace the wisdom of myth?

The story of the True Dragon is the allegorical story of a “real” dragon who decides to visit of one of his admirers. In this story, the student’s zeal for dragons was apparent in his collection of images of dragons. Intellectually, he was the acknowledged “expert” on dragons. Then, one day, a real dragon decided to honor this fan with a visit:

“Yeh Kung-tzu was a man who loved dragons. He studied dragon lore and decorated his home with paintings and statues of dragons. He would talk on and on about dragons to anyone who would listen.

One day a dragon heard about Yeh Kung-tzu and thought, how lovely that this man appreciates us. It would surely make him happy to meet a true dragon.

The kindly dragon flew to Yeh Kung-tzu’s house and went inside, to find Yeh Kung-tzu asleep. Then Yeh Kung-tzu woke up and saw the dragon coiled by his bed, its scales and teeth glittering in the moonlight. And Yeh Kung-tzu screamed in terror.

Before the dragon could introduce himself, Yeh Kung-tzu grabbed a sword and lunged at the dragon. The dragon flew away.” [5]

Most often, this story is meant to illustrate how it is important to have a teacher, take refuge and — more importantly — to practice, not simply to hang up pictures and study sutra. In other words, Buddhism in practice, rather than just form and intellectual comprehension.

Guanyin, Tara and Dragons

In Mahayana Buddhism, Guanyin, the Goddess of Mercy (Avalokiteshvara, Chenrezig) is often depicted riding a dragon. Likewise, Tara is depicted riding or standing on a dragon (see photos.) [For more on Guanyin and Dragons see the section below “ Legend of Guanyin, Dragon Girl and Sudhana”]

Why Guanyin and Dragons? We can assume, in part, her association goes back to her associations with the sea and Mount Putuo, her sacred place. “In Chinese art, Guanyin is often depicted either alone, standing atop a dragon, accompanied by a white cockatoo and flanked by two children or two warriors. The two children are her acolytes who came to her when she was meditating at Mount Putuo. [12]

The symbolism is very clear. Guanyin (and Tara) represent Compassion in Action while the Dragon represents actual practice of compassion and Dharma — the powerful activities that relieve the suffering of Samsara. [More on this below.]

Literally, Dragons are everywhere in Buddhism. Makara’s — literally meaning “sea dragon” — are ubiquitous in temples and even home doorways as guardians, and are one of the symbols found on the Vajrayana Dorje (Vajra Thunderbolt sceptre) and Bell (Ghanta). One of the dakini attendants of Palden Lhamo is called Makara-faced or Sea-Monster faced Dakini (Poor translation, it should be Sea-Dragon-faced Dakini.) [More on Makara’s below.]

Dragons represent nature’s forces in Buddhism

Dragons are directly associated with nature. Oceans, rivers and the heavens are often dragon deities in Buddhism. Since nature remains a vital part of Mahayana Buddhist spiritual paths, dragons have a pride of place as sovereign “elements of nature” — typically associated with the East, spring, and growth (Green Dragon), but also with fall and harvest (Brown or Yellow Dragon).

“In Eastern mythology, nagas are a class of being whose primary role is as protector and benefactor. Since their abode is the deep water, they are a source of knowledge and of fertility but they also guard the immense riches of the earth. Thus the Eastern dragon has mainly benevolent and auspicious characteristics but in Western mythology, the role of the dragon has been strictly curtailed rendering it into an ugly, greedy and jealous opponent of the Hero. It is the opinion of some that the reason for this has to do with the way people in the West view nature itself– as something to be vanquished.” — [Khandronet Note 6]

Prior to the Middle Ages, however, dragons in the West were mostly positive (or neutral) natural forces. Later, as non-nature oriented spirituality came to dominate Europe, Dragons began to be re-cast as “evil” or monsters. Saints, knights and heroes would “slay the dragon,” in part to symbolize man’s dominance over nature. In Eastern traditions, Dragons retain — to this day — their positive, nature-oriented personas.

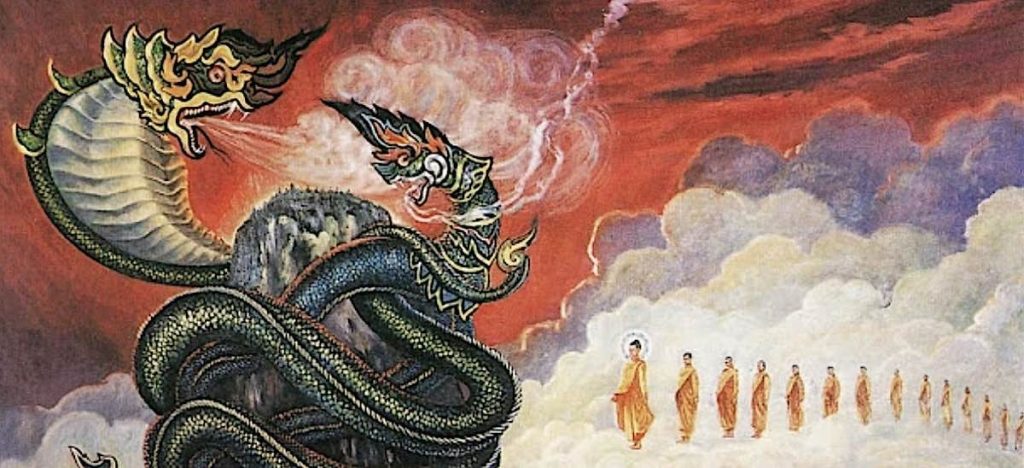

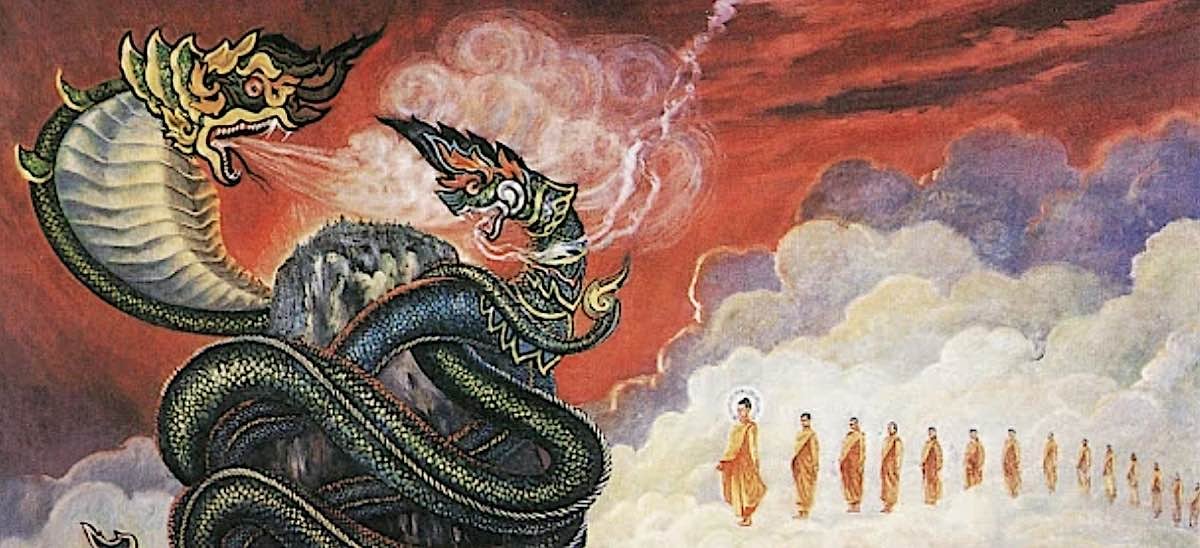

Dragons in the East predate dragon myth in the West — in China as early as 16th century BC, and in India (as Nagas) even earlier. Dragons are sacred to Vairochana, the Buddha of the East (or centre, one of the five Dhyani Buddhas), and are also often depicted with Vajradhara Buddha — the Vajrayana emanation of Shakyamuni Buddha. A nine-headed Naga (or dragon) protected Buddha is Sutra as he meditated under the Bodhi tree. In other words, they are important beings in Buddhist sutra and legend.

Since dragons are associated with nature’s great forces they can be considered both positively and negatively — but either way, requiring respect. From Khandronet: ” The rains that fertilize the land were attributed to the actions of the dragons, but so were the tremendous and devastating storms that sometimes occurred. These were attributed to the movements of the great celestial dragons as they emerged in the spring or descended to their caves in the autumn.”

True Dragon represents “practice”

Why does Buddhism still embrace the Dragon? In Buddhism Dragons symbolize importance of practice with intellectual understanding — the True Dragon in our Chan story above. They also represent Oneness with Nature — Dragon rather than “Mother Nature.”

It is for these reasons we often see Guanyin or Tara riding a dragon. As the embodiment of Enlightened Compassion, She (Guanyin or Tara) rides the awesome Dragon King, who represents Enlightened Activity. This tells us that while we might understand and embrace Compassion in our minds, this is not sufficient. The dragon is activity — compassion put into motion in the Samsaric world (or Mother Nature.) Comprehension and intellect alone are not enough. Activity and practice — putting compassion and wisdom into action — are vital to the Buddhist path. Likewise important are Oneness with all of Nature (represented by Dragon.)

Guanyin and Tara, above all, represent the saviour Bodhisattva, the activity of compassionate wisdom. Compassion without activity (the True Dragon from our opening story, where Dragons represent “practice) is only a concept. Concepts, without the activity of the dragon cannot benefit beings suffering in Samsara. Likewise, any being at “odds” with Nature is certain to suffer. (Tara, for example, helps protect us from dangers in the natural world. How? By helping us live in harmony with nature.)

Dragons in sutras

Guanyin’s relationship with the Dragon is a cherished one, that goes beyond symbolism. One of Guanyin’s main attendants is Lung-wang Nu, the daughter of the Dragon-king. Dragon-king Himself is considered a Dharma deity, symbolic of the great power. He often appears in Lalitavistara Sutra.

Similarly, Vairochana Buddha’s sacred guardian is the Dragon. Dragons are symbolically considered protectors of the Sutras.[5] Sagara, the Dragon King, is an eminent guardian of Avalokiteshvara in Sutra[3]. It is Sagara, whose name means “Ocean,” who presides over the world’s supply of rain, according to the Avatamsaka Sutra[4]. Chapter 12 of the Lotus Sutra contains the story of Sagara’s daughter, who later becomes a fully enlightened Buddha. [1]

White Jambhala and the Dragon

Dragons are also strongly associated with prosperity Buddhas and deities, such as White Jambhala, who inevitably appears on a dragon, as described in an exhibit at The Met:

“Although part of the jewel-born family associated with the Buddha Ratnasambhava, white Jambhala is said to have been born from the right eye of the compassionate bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara. He is identifiable by the dragon he rides and his gold sword, a variant of the khatvanga ritual staff, which he holds in his left hand. He alleviates suffering from poverty and sickness and purifies nonvirtuous karmic actions.” [10]

Dragons are pervasive in Buddhism. In Tibet, the Drukpa Lineage — “Druk” literally means Dragon — the Dragon Yogis. In China and Japan Buddhist Dragons are universal and celebrated. In India, where Dragons first emerged as Nagas, they protected Shakyamuni Buddha, and Makara’s (Sea Dragons) appear everywhere as guardians.

Makaramukha or Dragon-Faced Dakini

One important Enlightened meditational deity in Tibetan Buddhism is the Makara-Faced Dakini (Dragon-faced Dakini.) Sometimes this is English translated as Sea Monster-faced Dakini, which is an inaccurate western translation. It should be Makara-Faced or Dragon-Faced Dakini. She is part of the retinue of Palden Lhamo, Tibet’s most important Protector Enlightened Deity, but she also has her own practices.

Makara’s are sea dragons (not monsters) who can shift form like any dragon, but most often appear with a half dragon (sometimes described as crocodile-like) and half-elephant form. There are two other important “animal-faced” dakinis: Simhamukha Lion-headed Dakini and Sarvadulamukha Tiger-Headed Dakini.

As a “dragon” Dakini — for similar reasons to the representation of dragons with Guanyin (see above) — She represents activity of compassion and wisdom. Like other dakinis, she dances actively.

Auspicious in the East, stormy in the West

In Buddhism, and most Asian cultures, dragons are universally auspicious, typically considered deities (rather than monsters) who bring life-giving rain and fertility/wealth, and are often Enlightened heavenly beings. On the contrary, in ancient Western cultures — arising from Greek and Mesopotamian myth — dragons are more likely to be monsters, since man is seen as “opponents of nature” — destined to conquer nature — rather than its allies. Dragons in the East would typically be thought of in the same was as we’d think of “Mother Earth” in western myth. Especially later, as Christian myth supplanted early spiritual paths, the dragon became an adversary of noble heroes questing to kill them.

“Unlike its demonic European counterpart, the Tibetan dragon is a creature of great creative power; a positive icon, representing the strong male yang principle of heaven, change, energy, wealth and creativity. Dragons are shape shifters, able to transform at will, from as small as the silkworm to a giant that fills the entire sky. Dragons are depicted in one of two colors, green or brown. The green, or azure dragon of Buddhism ascends into the sky at the spring equinox; it represents the light’s increasing power in springtime and the easterly direction of the sunrise. The brown dragon is the autumn equinox, when it descends into a deep pool, encasing itself in mud until the next spring, but its spirit is still with the practitioner bringing wealth and health. The pearls, or jewels clutched in the claws of the dragon represent wisdom and health. The dragon can control the weather by squeezing the jewels to produce dew, rain or even downpours when clutched tightly. The dragon is the vehicle of Vairochana, the white Buddha of the center or the east.” [From a feature on Buddhist Symbolism, note 8.]

Dragons as Shape-Shifters

In Buddhism, where “Form is Emptiness, Emptiness is Form” (Heart Sutra), it is not surprising to find that dragons are of no fixed form. This is why you see can see them sometimes with horns, fish bodies, serpentine bodies, lion heads, or other attributes. They can shapeshift, even appearing as beautiful people, as other animals, or even shrinking so small they are invisible.

Eastern dragons require no wings to fly. The great and beautiful creatures fly in the air and swim in the sea — and move between worlds and dimensions — with equal ease. When the founder of the Buddhist Drukpa lineage in Tibet founded the lineage’s first monastery, it was on a site where he had seen nine wingless dragons soaring gracefully through the sky in a mystical vision.

They are not limited, “physical” creatures as portrayed in Western myths depicting knights slaying fire-breathing winged dragons.

Dragons are hard-wired into the collective consciousness

Dragons are hard-wired into the collective consciousness of all world cultures, according Joseph Campbell, a mythologist who expanded on the theories of psychologist Carl Jung, explaining “the dragon symbol is just one of the basic images people recognize without being taught.”[6]

In An Instinct for Dragons, anthropologist David E. Jones “proposed that over millions of years, natural selection imprinted upon our primate ancestors a recognition of the form of the dragon.”[6] Likewise, dragons are important and prevalent “beings” in Buddhism.

“There be Dragons”

Dragonlore is among the most ancient of human lore. Somewhat “dinosaur-like” in appearance, their legends are found in every ancient culture, from the Maya and Aztecs — “the plumed serpent god Quetzalcoatl” — to the ancient pre-history of the ancient cultures in and around India. Like Sanskrit, the Mother of languages, Dragons can be thought of as the “Mother” of mythological archetypes, predating most concepts. Formally, in direct lineage, legends of Dragons date back more than 17,000 years in China (to 15,000 BCE) — where they are always associated with good fortune. In India, Naga and dragon lore predate Chinese legends.

In European myth, dragons tend to symbolize “unknown territories” — per the phrase “There be Dragons.” They are often malevolent myths — likely derived from Greek legends of Typhon or Babylonian deities such as Tiamat — and popularized by Tolkien’s greedy Smaug in The Hobbit novel and numerous Hollywood movies. It is likely for this reason Dragon’s became associated with “evil” in the west. In the rest of the world, predating classical Greece and Babylon, Dragons are universally positive heavenly forces. In the 12-year cycle of the Chinese zodiac, dragon years are considered to be among the most auspicious.

In Buddhism, especially, Dragons are protective forces, Enlightened forces, who guard the Sutras, and represent the raw power of nature. Although Dragons may be thought of as mythological beings, in Mahayana Buddhism especially, at the ultimate level of reality, they exist as Enlightened forces and deities. That does not mean we will find fossils of dragons on the bottom of the ocean — but that they represent specific aspects of reality — and are no less real in spiritual terms than any other deity.

Buddhist Directional Protectors

Two of the five main Buddhist directional guardians — also known as the Auspicious Ones — are Dragons. These Five Directional Gods (four cardinal directions plus center) are Buddhist Protectors who remain important in Mahayana and include the Azure Dragon of the East, Yellow Dragon — or, often times the mythical Qiling (often depicted as a single-horned dragon-like creature) — in the center, the Vermilion Bird of the South, the White Tiger of the West, and the Black Tortoise of the North. [More on the five directional deities below.]

Legend of Guanyin, Dragon Girl, and Sudhana

There are many charming stories of Guan Yin and dragons, most with lessons in compassion, most notable the story of Longnu and Sudhana (a.k.a. Dragon Girl and Shan Tsai) who appear in the Lotus Sutra (Chapter 12) [7]:

“Many years after Shan Tsai became a disciple of Guan Yin, a distressing event happened in the South Sea. The son of the Dragon Kings (a ruler-god of the sea) was caught by a fisherman while taking the form of a fish. Being stuck on land, he was unable to transform back into his dragon form. His father, despite being a mighty Dragon King, was unable to do anything while his son was on land. Distressed, the son called out to all of Heaven and Earth.

“Hearing this cry, Guan Yin quickly sent Shan Tsai to recover the fish and gave him all the money she had…. Shan Tsai begged the fish seller to spare the life of the fish. The crowd, now angry at someone so daring, was about to chase him away from the fish when Guan Yin projected her voice from far away, saying “A life should definitely belong to one who tries to save it, not one who tries to take it.”…

“The crowd realizing their shameful actions and desire, dispersed. Shan Tsai brought the fish back to Guan Yin, who promptly returned it to the sea. There the fish transformed back to a dragon and returned home…

“But the story does not end here. As a reward for Guan Yin’s help saving his son, the Dragon King sent his daughter, a girl called Lung Nue (“dragon girl”), to present to Guan Yin the ‘Pearl of Light’. The ‘Pearl of Light’ was a precious jewel owned by the Dragon King that constantly shone. Lung Nue, overwhelmed by the presence of Guan Yin, asked to be her disciple so that she might study the Buddha Dharma. Guan Yin accepted her offer with just one request: that Lung Nue be the new owner of the ‘Pearl of Light’…”

In popular iconography, Lung Nue and Shan Tsai are often seen alongside Guan Yin as two children. Lung Nue is seen either holding a bowl or an ingot, which represents the Pearl of Light, whereas Shan Tsai is seen with palms joined and knees slightly bent to show that he was once handicapped…”[7]

Buddhist Dragons around the world

In Northern and Eastern Buddhism especially, Dragon is the “Protector of the Dharma” and also “Protector of the Shakyamuni Buddha.” In early Sutras, Dragon and Naga deities attend many of Buddha’s teachings. The image of Buddha meditating under the protective watch of Naga King is ubiquitous.

In China, Japan and Korea, Dragons are always powerful forces, and almost always auspicious, heavenly powers, associated with oceans, weather, heavens, thunder, and life-giving rain.

In India, Dragons are typically associated with Nagas, who can be both important deities (such as the Naga King) or malevolent forces — although dragons are always considered auspicious or positive forces. (This is no different from other beings who can be Enlightened or evil, such as people.) ” In the Pali Canon, nagas are treated more sympathetically, but they remain eternally at war with garudas, except for a brief truce negotiated by the Buddha… nagas came to be depicted as guardians of Mount Meru and also of the Buddha.”[5]

In Tibet, Dragons are equally prominent, although Nagas and Dragons are somewhat differentiated. Many Nagas are associated with disease and misfortune due to the “watery” associations, while Dragons are clearly elevated to important roles as Protectors “whose thunderous voices awaken us from delusion.”[5]

Thailand’s Buddhist dragon temple:

The Dragon Yogis

In Tibet and Busan especially, dragons take on extra significance. The Drugkpa Lineage literally translates as “Dragon” Lineage, came from the line of the Mahasiddha Naropa (born 1016 CE in India). Naropa’s later incarnation, Tsangpa Gyare Yeshe Dorje was the founder of the Drukpa lineage. [See video documentary below.]

Famously, Tsangpa Gyare Yeshe Dorje saw nine dragons flying over a site near Lhasa, Tibet, and decided to build a monetary on that auspicious spot. He then named his lineage Drugkpa, literally “Dragon.” Vajrayogini Herself — the Queen of the Dakinis — predicted the Drugkpa lineage would become “legendary.”

“As Tsangpa Gyare Dorje was looking for a Holy site to set up a monastic institution, he witnessed nine dragons that flew into the sky with a loud clap of thunder!” — Video, The Dragon Yogis.

Kobo — Azure Dragon of the East

Kobo is associated with Vairochana Buddha, the Buddha of the East (in some systems the central direction). In the Yi Ching his Yao symbol is associated with:

- Green

- Spring

- Rain

- Heavens

- East

- Wood

- Yang Energy

- Young Yang

In fact, in Yi Ching (Yijing, Book of Changes) Dragon represents Yang while Tiger represents Yin, the two main opposing forces in Daoist philosophy — a philosophy that is complimentary and co-influences (both ways) Buddhism.

In China, also, there is a Western Brown (or Yellow) dragon, representing autumn and harvest.

Houtu — Yellow Qilun “Dragon” of the Centre

In the central direction, is another important Dragon Deity, Yellow Dragon — also associated with the mysterious Qiling (Qilin) who represents:

- Yellow

- Midsummer

- Central direction

Although the Qilin are unique, manifesting as the “unicorn of dragons” with one horn — and they have unique combinations of features, they are considered a form of “dragon.”

The other three directional forces (deities or gods) — aside from the two dragons — are:

- Zhurong: Vermillion Bird, Garuda or Phoenix for South, Summer, Red, Fire, Old Yang

- Jokushu: White Tiger, West, Autumn, White, Metal, Young Yin

- Genmei: Black Tortoise, North, Winter, Black, Water, Old Yin

Makara’s: Sea Dragons

In ancient myth of the Indian sub continent, Makara’s are pervasive.

“Makara is a Sanskrit word which means Sea Dragon or Water Monster. It is a mythical sea creature. It is usually described as a half terrestrial animal such as an elephant, crocodile, or deer in the frontal part and half-aquatic animal in the other part, usually of a fish or a seal… Makara is equivalent to the zodiac sign Capricorn, which is a sea goat. It is considered to be the vehicle of Hindu river goddess Ganga, Narmada and the sea god Varuna.” [9]

Makara’s as ornaments are protective. Several Hindu gods — Shiva, Vishnu and Surya — where Makara shaped earrings rings, called Makara Kundalas. Buildings and temples have statues or “heads” of Makara’s as protectors. This is similar to the Viking practice of dragon-headed figureheads of ships to “scare away” evil. In Buddhist temples, Makara’s appear on temple roofs and doorways. Makara’s also appear on sacred bells and dorjes in Vajrayana Buddhism.

NOTES

[1] Image of Four Guardians attribution By RootOfAllLight – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/hat wouldw/index.php?curid=88889824

[2] About the Lalitavistara Sutra https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lalitavistara_S%C5%ABtra

[3] Sagara the Dragon King https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/S%C4%81gara_(Dragon_King)

[4] Avatamsaka Sutra https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Avatamsaka_Sutra

[5] O’Brien, Barbara. “Dragons in Buddhism.” Learn Religions, Feb. 8, 2021, learnreligions.com/dragons-449955.

[6] Khandronet.org Dragons http://www.khandro.net/mysterious_dragon1.htm

[7] Guan Yin, Guan Yim, Kuan Yim, Kuan Yin https://www.nationsonline.org/oneworld/Chinese_Customs/Guan_Yin.htm

[8] Buddhist symbols and iconography https://www.baronet4tibet.com/symbolism-animals.html

[9] Makara, Sea Dragon https://medium.com/age-of-empathy/tale-of-makara-a-hindu-mythical-creature-f55998bb7779

[10] White Jambhala featurette at the Met Museum https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/39213

[11] Cambodian sculpture fragment: Buddha Protected by a Seven-headed Naga

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guanyin[12] Guanyin Wikipedia: