Most people watch movies. Some watch or read fiction, some documentaries, some science fiction, some, fantasy, some romance, some comedy — some of us watch all of them! What’s the difference/ All of them are movie-watchers. Likewise for books. I might like, one, two, or all genres.

Buddha taught in this way, too, to suit different “tastes” or styles.

Hiker, Bus Driver or Space Shuttle Pilot?

Or, let’s use the metaphor or hiker, bus driver and space shuttle. According to Sutras, Buddha taught with skillful means. For many of us, he taught the path of “conduct” and morality and renunciation and contemplation — the methods of Theravadan Buddhism. This is the mindful walker, deliberate, careful, aware, focusing on their breath and their behavior. He is compassionate, walks carefully, wouldn’t step on an ant or hurt any being, but he has a destination and he’ll arrive there alone.

For we less “peaceful” types, those of us bound up with families, friends, society, and helping others, he presented the great “bus” vehicle of Mahayana. For these society-builders, he taught the path of compassion and Bodhichitta, active loving-compassion, the Bodhisattva path, and Buddha Nature. This is the hero who, instead of walking, drives a big bus, and fills every seat on the vehicle. This is the person who won’t leave the disaster zone until everyone is one board!

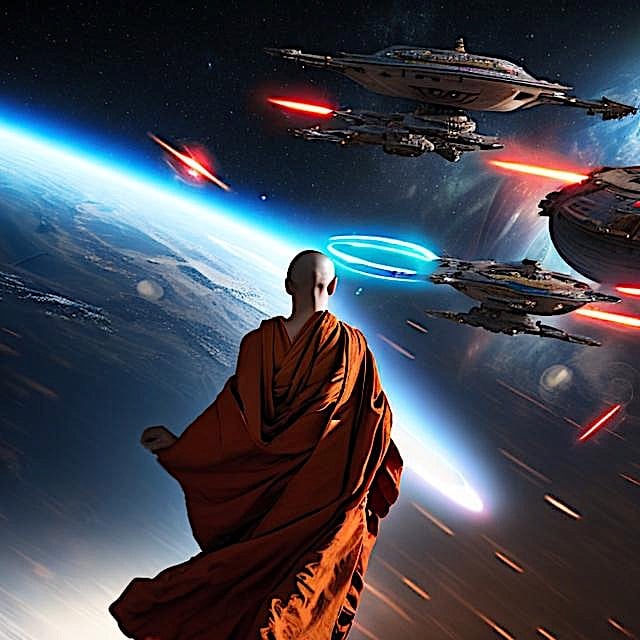

Still others are daring enough pilot the first space shuttle to Mars. These are the people who learned and practiced the Vajrayana and other esoteric forms of Buddhism, which embraced all of the other teachings, but focused more extensively on the illusory nature of reality. This is the explorer, the dare-devil, still heroic, but searching “out there” for the answers.

And, what about Zen or Chan, Dzogchen or Mahamudra practitioner? This is the “no moving” sitting in stillness crowd.

In our earlier metaphor of movies, the

- Theravada practitioner is our documentary and drama fan

- Mahayana practitioners is our metaphorical heroic adventurer and romantic comedy crowd enthusiast

- Vajrayana is no doubt the science fiction crowd — driven by logic, but seeing beyond the fantasy.

- Zen/Chan Dzogchen and Mahamudra are the “no movie” crowd who are happy sitting on the warm beach than in the movie theatre.

If you hate these two metaphors, how about an architectural example?

What’s the difference? The three-story building

On, to the construction industry. In this metaphor;

- Theravada is the foundation and frame our building.

- Mahayana is when we decide to build the first floor or our house.

- Ultimately, as our family grows, we need a second floor addition, the Vajrayana.

- Finally, when the grandkids arrive, we finish the “granny suite in the attic” and retire — the Dzogchen, Chan / Zen, Mahamudra.

When we were bachelers, e could very well have lived in a basement or foundation of a building (In our metaphor, Theravadan methods, building our foundation.). Later, maybe we’ve started a family, so we buil a first floor on our foundation so that we can protect more people. When we have children, we need a second floor. When the children grow up, we have more time for practice, and more security (foundation) and our loved ones are protected — so we finish the attic and move into the granny suite.

But, you can’t build that second floor, or finish the attic until you have a solid foundation. In Buddhism, this foundationalso known as the Noble Eightfold Path.

Four paths, plus one or two

There is really one path, ultimately. Typically, though we talk about three paths: Theravada (the Elder Path); Mahayana (the Great Vehicle, which includes Pureland and Zen/Chan); and Vajrayana (which includes Dzogchen and Mahamudra.)

The difference? The destination and underlying foundational teachings are the same. The practical methods are different. In the interests of conciseness (but not accuracy) we’ll call these:

- Theravada: Path of conduct and concentration

- Mahayana: Path of all-embracing compassion.

- Vajrayana: Path of seeing the true nature of existence.

- Dzogchen and Mahamudra: the inner path of no longer needing to see; or realizing the true nature of reality.

Why did Buddha teach this way?

Because, in his unlimited wisdom, he understood, and developed a method for people who are all attached to different things:

- Attached to habit: For them, Theravada is imperative. First we have to break that cycle of poisons and attachments.

- Attached to worry and concern: They care so much for other beings that their worry is ceaseless until everyone is safe! For them, Buddha transmitted the Mahayana.

- Attached to concept: Other people have minds that will never stop working, theorizing and visualizing or imagining — for them, Buddha transmitted the Vajrayana.

All three converge at the final destination.

Buddhists, by nature, are tolerant. We may argue amongst ourselves that Mahayana is more “compassionate”, or Theravada is more pure and the “original teaching”, or Vajrayana is truer to the essence of the teachings, but the truth is, none of these are right. Theravada is right for some of us. Mahayana is right for others. Vajrayana for a much smaller segment. All are authentic and pure — but teach core truths in different ways.

All three, build on the previous. The Eightfold Noble Path is the foundation of Mahayana. The Mahayana (eightfold path with focus on the Bodhisattva Path) is the foundation underlying Vajrayana. The Vajrayana is the foundation of Dzogchen, or Mahamudra.

For example, gods and supernatural

To illustrate perceptual shifts, in Theravadan Pali Sutta, Buddha taught that the gods and deities were of no importance, and likewise notions of supernatural and afterlife. Sometimes, people say he taught “atheism” — but he didn’t explicitly teach this. He simply said that metaphysical matters are unimportant.

Deities, demons, supernatural are unimportant — but ultimately so is our ego, our houses, our bank accounts, and everything else we are attached to. The point is, we to detach from clinging to all of these things — not to reject them.

We can still have a house, help others survive, donate to charity, drive our car to work, pray to deities, fret over that seeming run of bad luck. That’s relative reality. We live it. At the same time, we aim to live without being attached to any of these things. We drive our car, but don’t have to obsess over the latest model. We have a house, but don’t envy others with bigger houses. We experience bad luck, but we move on, with discipline, remaining focused on helping as many beings as possible.

So, why do some Buddhists appear to have a vast pantheon of gods and deities? This is iconic of the grand scope of Mahayana. All beings, be they insects, humans, animals, serial killers, gods, ghosts or demons — every one of them must be saved from Samsara in the grand scope of Mahayana. Why do we sometimes, for example, see a Buddhist who also has the Virgin Mary on her altar? Or Kali alongside Buddha? In the Mahayana, all beings and all forms, ultimately are of One Essence or “one taste.” This is the grand vision of Buddha’s ultimate and most astonishingly beautiful and pofound Prajnaparamita Sutra:

“Form is emptiness. Emptiness is form.”

There is room in this vision for everyone, every being, from cellular life, to two-legged life, four-legged life, eight-legged life, and even angelic, divine or demonic. All are sentient beings, who at the ultimately level, are, in of one essence.

Does that mean deities and demons and ghosts are not real? They are as real as humans, insects and animals. Why? Because in Buddhism, humans, insects and animals are no more real than deities, ghosts and demons. They are the products of our attachments, clinging and ego.

Multiple forms of renunciation?

One way to renounce is to shave our heads and beg for food — the ultimate commitment to a renounced path. Another way to practice is sometimes called “lay renunciation”: to make a living (without harming others), sharing with others, feeding the monk community, supporting the Sangha, helping spread the Dharma teachings, being kind, reducing the suffering of others. It’s not right, or wrong — it’s a different method. A third, the way of the Mahasiddha, is to grow our hair long, look at everyone with wild eyes, and practice forms of “crazy wisdom” — but maybe that’s not for 99.999999999 percent of us.

It really depends on our capacity, and resources. Full renunciation is certainly suitable to someone who is in a position to live simply, retreat into meditation and renounce all attachments. Theravada concentrates on the eightfold path: right view, right resolve, right speech, right conduct, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, and right samadhi (meditation or concentration.)

But, for many, the notion of renunciation isn’t practical. Lay practitioners, for example, focus only on five aspects or renunciation. We wouldn’t survive long enough to be in a position to renounce everything.

Mahayana — Great Vehicle

Embracing “everything,” which is the concept behind Mahayana — tanslates as “great vehicle” is yet another metaphor. In this metaphor — as one of my teachers put it: “we have a great big bus with room for everyone to jump on board.” We have room for daily life, caring for others, and practicing renunciation when we get home from our daily survival grind, or during retreats.

In fact, we are expected in the Mahayana, to think of others before ourselves, which is somewhat incompatible with full renunciation.

In Mahayana, we interact and try to care for all beings, both seen and unseen. In the teachings on Shunyata — and especially the profound “Form is emptiness, emptiness is form” teaching in the Heart Sutra — there’s room for deities, demons, ghosts, hungry ghosts. Today we might call these higher self (our own Higher Buddha Nature as Enlightened deities; and forces of nature as the worldly deities), psychological issues (demons), and addictions (hungry ghost).

This is also the concept behind “great vehicle” as we are driving a gigantic bus with room for every being in the Universe, by whatever name or label we affix to them. Until we all realize we are One Nature and Buddha Nature, we help each other as suffering, ego-attached beings.

For those who take this to the ultimate conclusion, there is the Vajrayana — translated as the “indestructible vehicle.” Why indestructible? Because here, the concept is the illusory nature of all beings — and the teaching on impermanence takes on a different “perceptual reality”. We may be impermanent in terms of ego and the notion of self-existence, but we also already have Buddha Nature and are indestructible, once our notions of ego fall away. We migrate through various manifestations and lives due to our clinging to illusory concepts. In this view, we are indestructible because we are part of the one, giant multiverse; only our ego and our illusions are impermanent and attached to our current “life.”

This is why Vajrayana is often compared, for example, to the movie the Matrix. If we can transcend the dream-like state — in the movie the Matrix, being in cocoons dreaming our lives — then we can “wake up” in the real world unhampered by attachments and limitations. This is why it’s also called the fastest path — although arguably the most difficult because it’s easy to fall into new illusory traps when undertaking meditative methods such as self-generation. The fulfillment is only possible when we finally reach the “completion stage” of practice and go within.