In this feature, I’ll make a crazy argument — but bear with me. Wing Chun, the venerable martial art created by Buddhist Nun Ng Mui perfectly (pun intended) showcases the Six Perfections taught by Buddha: Generosity, Discipline, Patience, Diligence, Concentration, and Wisdom.

One of Wing Chun’s most famous students, Bruce Lee, once said, “Be as water.” It was meant as a martial arts life philosophy, but there is no doubt it directly mirrors Buddhist thinking [Video embedded below.] Bruce Lee said:

“I said empty your mind. Be formless. Shapeless, like water. You put water into a cup, it becomes the cup. You put water into a bottle, it becomes the bottle… Water can flow, or it can crash! Be water, my friend.”

Bruce Lee — “Empty your mind… be as water.”

You may wonder, in a story about Buddhist Nun Ng Mui and Wing Chun, why did I lead with Bruce Lee? Well, aside from being his fan, his speech was one reason I associate Wing Chun and Buddhism. (Oh, I know he created his own martial art, but Ip Man taught him Wing Chun — it’s all part of the legend.) The other reason I associate Wing Chun and Buddhism, is, of course, the wonderful, amazing and inspiring story of Buddhist Nun Ng Mui — the inventor of the Wing Chun that Bruce Lee so perfectly embodied.

In this feature, I’ll venture into legendary territory, exploring the legends of not only Wing Chun and Buddhist Abbess Ng Mui but Bruce Lee and Ip Man — but with an ulterior motive! I hope to demonstrate why Wing Chun especially (and to some degree other martial arts) reflects the Six Paramitas (Perfections) taught by Buddha!

By Josephine Nolan

The legend of the great Buddhist Abbess Ng Mui

Stories of female warriors are scattered throughout history, with many mixing legends with fact. One such story is that of the Shaolin Abbess Ng Mui (or Ng Mei), who invented the martial art Wing Chun — and who really needed no legend to make her story exciting. (Okay, Michelle Yeoh in the movie Wing Chun as Ng Mui is pretty fun — short trailer below — and she’s great as always, but let’s call that legend. For fun we’ve embedded some martial art flicks trailers — of course, these are not historically accurate!)

The legend of Wing Chun is wonderful and meaningful, but the real subject of this feature is the six ways Wing Chun’s discipline mirrors Buddhist practices. I introduce the idea that these six practices align with the Buddha’s teachings on the Six Perfections: Discipline, Patience, Diligence, Concentration, Wisdom and Generosity.

(Presented in the last section after we have fun with the legend. Let us know what you think in the comments!)

Michelle Yeoh stars in a not-entirely-accurate legendary martial arts movie Wing Chun — as the founder of Wing Chun, Buddhist Abbess Ng Mui — alongside a very young Donnie Yen (who would later play Ip Man in later movies. (Ip Man was a famous master of Wing Chun).

As a Buddhist nun, she wanted to create a non-lethal martial art for nuns and monks — for both defense and health (since nuns and monks spend so much time sitting!) We can’t know, since hundreds of years have passed, but I like to think she also created Wing Chun to reinforce Buddhist practice as it brilliantly reflects six Buddhist principles and practices — which I’ll discuss below. (See if you agree. If not, please comment below!)

This is the very same martial art that many most associate with Ip Man, the famous master of Bruce Lee and a legend in his own right with many movies, series, and books detailing his own story. Yet it is Buddhist Shaolin Abbess Ng Mui who created Wing Chun, in an attempt to create a less lethal and more effective Shaolin martial art for self defense.

Buddhist Abbess of Shaolin, one of the Five Legendary Elders of Shaolin, is inspired (at least, in legend) to invent Wing Chun after watching a Crane fight a snake. While this is likely embellishment, it is part of the wonderful legend of Ng Mui and Wing Chun.

This feature will dive into her amazing story, her legends, and why Wing Chun is also a parallel discipline to Buddhism — and why she is an inspiration and role model for many Buddhists and women around the world.

The rich history behind Wing Chun

Manchurian invaders broke through The Great Wall in 1644. They ousted the Ming dynasty and established the Qing dynasty, which ruled for the next 267 years. It was then that the now-famous Shaolin temple became a haven for learning, practicing, and mastering martial arts in secret.

There was an increasingly desperate need for the Ming peoples to learn martial arts to be able to defend themselves, but the traditional Shaolin Kung Fu styles took 15-20 years to master. This timeline was simply too long for the urgency of the situation, and so The Five Ancestors devised a training program that would result in an effective martial artist in just 5-7 years.

Michelle Yeoh starred in the old classic Wing Chun. (It’s fun, but not even close to historically accurate. But fun!)

The Kung Fu styles of Shaolin were incredibly effective and soon gained prominence to the point that the Manchurian government attacked the monastery. Their first attempt where they sent troops to do the deed was unsuccessful, and so they changed tactics. Their second attempt involved convincing some of the monks inside the monastery to betray their companions. These monks set fire to the monastery, and soldiers attacked it from outside.

The five grandmasters of the monastery, however, escaped: Abbots Pak Mei and Chi Shin, Masters Fung To Tak and Miu Hin, and Abbess Ng Mui.

Many styles of Kung Fu can trace their lineage to these Five Ancestors. Unfortunately, as this time period involved so many tumultuous happenings, the records are fraught with inconsistency and gaps as martial arts practitioners were forced to hide to stay alive. [1]

Ng Mui fighting with Wing Chun.

Ng Mui and her martial arts prowess

Ng Mui is our heroine’s name in Cantonese. In Mandarin, her name is Wu Mei, which translates to ‘five plum’, an allusion to the five-petal plum blossom which signifies the early spring. This is all worth noting because the expression ‘five petals’ also has a connection with Bodhidharma’s transmission verse:

“I originally came to this country (China)

To transmit the Dharma and save deluded beings.

When the single glower opens into five petals

Then the fruit will ripen naturally of itself.” [2]

Michelle Yeoh staring in Wing Chun in the 1990s movie — just because there are no photos of Buddhist Nun Ng Mui. In the movie she gloriously portrayed Ng Mui, albeit with some “embellishments.”

History of Wing Chun

Chinese martial art circles have long debated the exact history of Wing Chun as well as Ng Mui. Generally, the most accepted is the oral tradition of Wu Mei Pai.

According to this version of the story:

Abbess Ng Mui was born to a Ming General as Lu Si Neung. When the Ming dynasty seemed as if it were to be overwhelmed by the invading Qing, Lu Si was sent away so that she might survive and carry on her family’s traditions.

Although she developed her skills in the Forbidden City, she was already an accomplished martial artist. In this version of the story, she took refuge in the White Crane Temple of the Kwangsi Province (although other tales instead place her in the Shaolin temple of the Hunan Province). She became a rebel and was vehemently anti-Qing, and her fighting style employed lightning-fast counter attacks and movements from Qigong and Bodhidharma.

This style of hers is said to have become what is now known as the White Crane Kung Fu style, which most give her credit for creating. This style was so effective and deadly, that it was the style of choice when people wanted to kill martial arts masters, and soon came to be known as one of the deadliest styles in the entirety of China at the time.

Buddhist Nun Ng Mui teaches Yim Wing Chun from a martial arts film:

The birth of Wing Chun – beauty and the beating

Ng Mui didn’t like that her Kung Fu style became synonymous with murder. According to the legends, this was why she left the temple, to create an even deadlier style to counteract White Crane Kung Fu. Whether she left the temple she was in (be it the Shaolin or the White Crane temple) in order to escape the Qing oppressors or her own art gone awry, Ng Mui left, alone.

In some legends, there is an insert in this part of the story that goes: Ng Mui escaped the burning Shaolin Temple and sought refuge at the White Crane temple. She saw a snake and crane engaged in combat during her training one day, and was inspired to create a new martial arts style based on their elegance, grace, and swiftness.

After this, the legends all seem to agree on a few key aspects, although the details understandably vary greatly. On her travels, Ng Mui met a young girl called Wing Chun. The girl’s beauty had caught the eye of a suitor who had power over her (in some stories this is because of status and political power, in others he is merely a large brute) and wanted to marry her. She had rebuffed him many times and had no interest in him, so he had promised to marry her by force.

Ng Mui took pity on the girl and agreed to teach her how to not only defend herself, but overcome her foes. Wing Chun became Ng Mui’s student, but they only had a limited time span to accomplish their goals.

Ng Mui created another form of Kung Fu, whose success did not depend on brute strength and size as Wing Chun was just a small, young girl. It was also far easier to learn than other styles, as Wing Chun was an absolute beginner with no martial arts knowledge.

Wing Chun trained until she became a master of this new style that Ng Mui created for her, and went on to challeng the man who wished to marry her, defeated him, and sent him on his way.

Ng Mui named her new style after its first student and inspiration. Before she left to continue her travels, she asked Wing Chun to honor Kung Fu traditions.

Donnie Yen returns to movies about Wing Chun in later years as the legendary Ip Man, Wing Chun master and teacher of Bruce Lee:

Wing Chun and Buddhism — six Paramitas

There are many legends surrounding Ng Mui and how exactly she created Wing Chun, but regardless of their differences, the martial art as it exists today is one that embodies grace, resilience, patience, and the strength of yielding to a force rather than fighting against it. [3]

There are many similarities that can be drawn between Wing Chun and Six Paramitas in Buddhism, and here are just some of them.

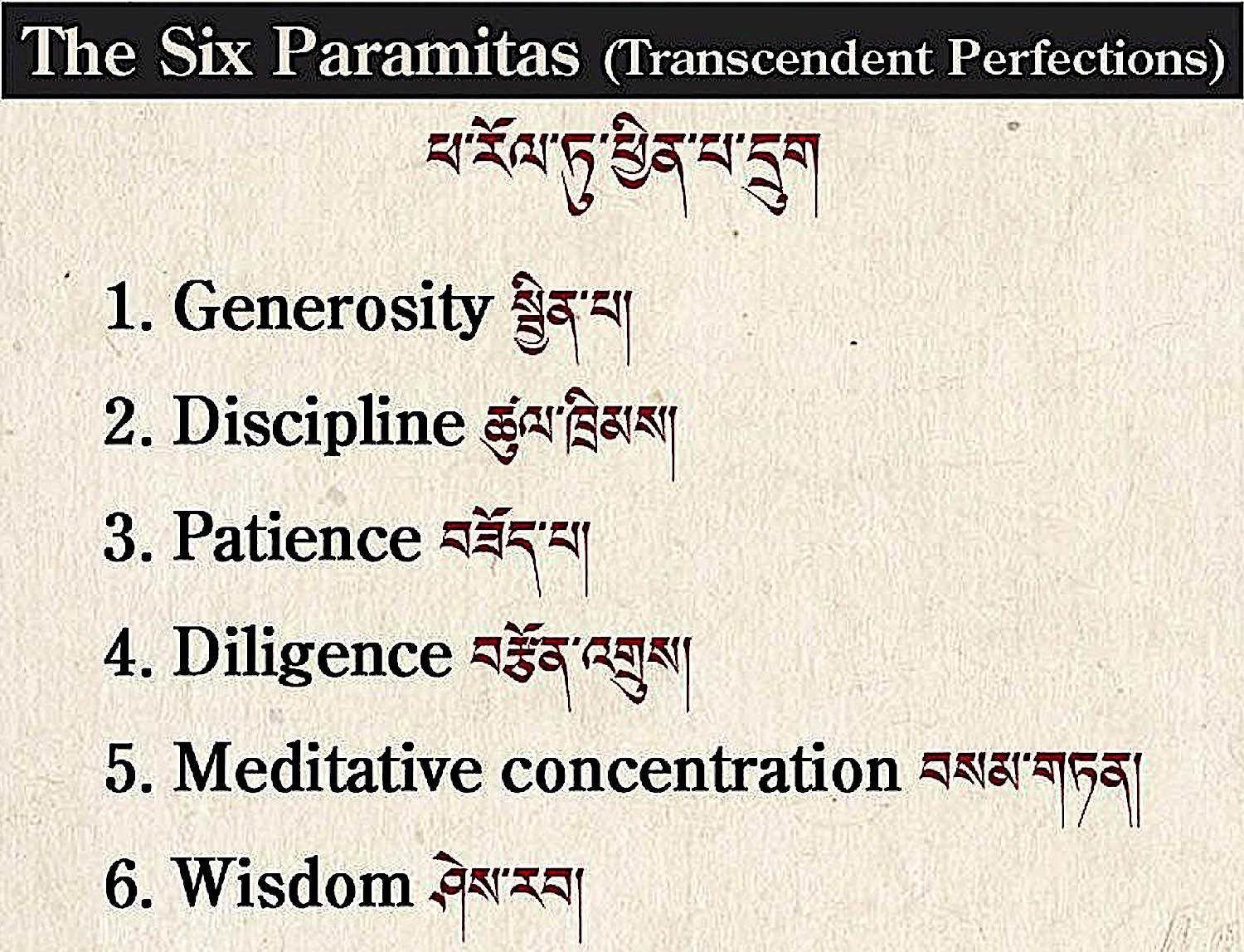

The Six Paramitas: Generosity, Discipline, Patience, Diligence, Meditative Concentration and Wisdom — mirror many of the aspects of Wing Chun training. You’ll need all of these in both Buddhist and Wing Chun practice!

Bruce Lee explains the concept of “water” as it applies to Wing Chun — and Buddhism:

1. Paramita of Generosity: yield to force

Trying to align the six practices of Wing Chun with the Six Perfections is the most difficult here. Generosity is a broad concept, as taught by Buddha. But, as a practice, how it applies in Wing Chun is in the ‘yielding to force’ — which almost defines the art.

The philosophy behind Wing Chun is, as Bruce Lee famously put it, “to be like water.” Water takes the shape of whatever container that you put it in. It can thunder over boulders and shape them according to its will, and it can gurgle softly as a babbling brook.

Wing Chun is like water. While it can be a very effective martial art, it is also as graceful, thoughtful, and knows when to yield to a force. It adapts to its situation and is a responsive practice. Buddhist Abbess Ng Mui designed it to be a non-lethal form of martial art.

Buddhism teaches that yielding to forces that seek to oppose us is a powerful solution. Letting go of ego, pride, and a focus on the self will allow troubles to wash over us. Opposition isn’t something to struggle against, but rather to allow.

Other martial arts also incorporate mindfulness, as first taught by Buddha. Here, training in Judo often includes sessions of mindfulness and meditation, as shown here on Ichinomiya Beach, Kagawa, Japan. Judo was also founded by a Buddhist.

2. Paramita of discipline

There can literally be no argument on this one! Both Buddhism of all lineages and Wing Chun require discipline to succeed. Succeed in what, you ask since isn’t the point in Zen to “strive without striving?” — Ah, exactly!

Wing Chun is a rigorous discipline that requires hard work, determination, and commitment. It has fantastic results, but only for those who put in the work to obtain them.

In Buddhism, before attempting more complicated practices, it is necessary to master the ‘beginner’s form’ just like in martial arts. There is a reliance on learning from someone who knows more than you do so that you are guided through learning stages of increasing complexity and difficulty. [See our previous feature, Dharma in Motion — discussing Kung Fu and Buddhism>>]

The Buddha himself taught of reaching enlightenment in a way that was disciplined and was achieved by putting in the hard work and effort yourself. Each person’s path is unique. You can never achieve mastery of Wing Chun or Buddhism by blindly following another, only by putting in the hard work yourself. The basics can be taught — but we must take the journey ourselves.

The great monk Bodhidharma brought Chan Zen teachings to China from India and influenced the Shaolin Temple and martial arts. He taught future generations of Buddhists the importance of “the journey” exemplified by his own incredible pilgrimage to China. He is the legendary inspiration of Kung Fu in Shaolin Buddhism.

3. Paramita of Patience: its about the journey, not the destination

Wing Chun is for self-defense, but it’s also about the journey. The name Wing Chun means “song of spring”. Ng Mui supposedly named the art for her student in the legends, but it also reflects her vision for her martial art and its values. She wanted it to be “an everlasting springtime achieved through great effort” [4]. Spring is about rebirth, rejuvenation, and building on what is already known. It isn’t about the destination, but rather about the journey to get there.

In Wing Chun, and most martial arts, patience is cultivated. It is required.

Similarly, Buddhism focuses on the path to enlightenment, where people must learn to let go of their earthly desires and cravings so that they can achieve realizations. It is about the journey. About striving, without striving. Just think of the long, patient pilgrimage of Bodhidharma, on foot, from India to China! That’s the journey. That’s patience.

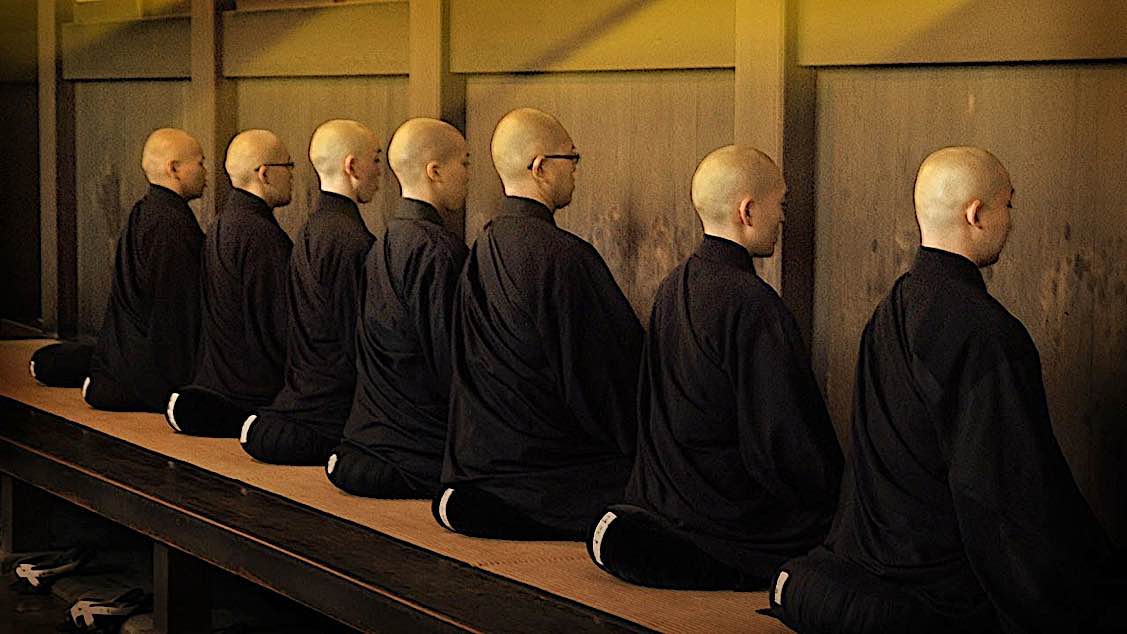

Zazen, silent sitting meditation — classically, facing a blank wall — is, to some people synonymous with Zen. It also demonstrates “striving without striving.”

4. Paramita of Diligence: beyond limitations

Both Buddhism and Wing Chun expressly deny limitations. In Buddhist philosophy, with diligence, we all can achieve Enlightenment. In Mahayana and Chan/Zen — which align well with Kung Fu and Wing Chun — every being has Buddha Nature. We cannot be limited by our bodies, our negative karmas and obstacles. Ultimately, we will — with diligence — push beyond our apparent and illusory limitations.

Whether the legends are true or not, Wing Chun is designed for people to be able to defeat their opponents regardless of size. It doesn’t depend on brute strength, but on knowledge, skill, attitude, and yielding to opposing forces.

5. Paramita of Concentration: Mindfulness

Many martial art styles are overly complicated in a bid to impress and intimidate opponents, but Wing Chun is direct, efficient, and elegantly simple. Every single movement is deliberate, mindful, and purposeful. This mindfulness is not surprising, given Ng Mui’s Buddhist roots and mastery of Shaolin Kung Fu.

Without perfect mindfulness, Wing Chun doesn’t work. You can’t anticipate, you flow with your opponent. You counter them with their own force and movement. You can’t do that if you’re trying to analyze or anticipate.

Likewise, Buddhism teaches us to be mindful of what we do. Mindfulness meditation allows us to make each and every one of our choices and actions meaningful. We can ponder without pondering, by staying in the present — not worrying about the past, or trying to anticipate the future. By not reacting, we put aside emotions such as anger and hate.

Martial arts like any physical activity involves listening carefully – not just to your teachers and peers, but to the feedback your own body gives you – so that you can learn what works, what doesn’t, and how you can do better. This careful dialogue with the self as well as others works just like mindfulness.

6. Paramita of Wisdom: striving without striving?

Why do Buddhist lineages such as Shaolin and many temples in Japan, Korea — and around the world — emphasize martial arts? In part, it’s the discipline, and also benefits to concentration, mindfulness and health.

Wing Chun, however, goes a step further. There is much less emphasis on “competition” and winning in Wing Chun. It’s a very Buddhist philosophy of “striving without striving.” As Bruce Lee said, “Be as water.”

Many martial arts focus on being the best and staying in the top spot for as long as possible. Instead, Wing Chun concentrates on improving and never stagnating — striving without striving. It’s designed for self-improvement, not just of the body but of the mind and spirit as well.

Buddhism also teaches of always striving to do more, learn more, and be better — without striving or focusing on a goal. In Zen, this this is especially captured in the Soto Zen idea of “just sit” without purpose, without a goal. The moment you have a goal — you are attached and craving. Strive without a goal, without attachment to a mission, and you live the Wing Chun and Buddhist philosophy.

Striving without striving, and the notion of “emptiness” as described by Bruce Lee, describe succinctly the heart of the Paramita of Wisdom:

Form is Emptiness, Emptiness is Form

Conclusion

There are many strong parallels between Wing Chun and Buddhism — not surprising considering the inventor was a well-known Shaolin Buddhist nun. Ng Mui created it as a means of self-defense that would transcend the confines that a smaller body facing a larger one had. It is swift, decisive, meditative, and humble.

This non-lethal style doesn’t focus on strength, but rather on mental discipline and practice. Martial arts, whether Wing Chun, or Kung Fu or any other discipline, embody many of the principles of mindful discipline taught within Buddhism — and most especially the Six Perfections (Paramitas) of: Generosity, Discipline, Patience, Diligence, Concentration and Wisdom.

Sources

[2] Shaolin Templi>>

[3] Ng Mui>>

Other sources

Wing Chun Philosophy>>