Buddhism speaks in terms of “Innate Enlightened Potential” or “Buddha Nature”. Cognitive Science speaks in terms of “Unified Single Mind.” Emptiness, or Shunyata, is also a Oneness perception of reality. Removing “ego” from our perception results in Oneness (Emptiness) which Buddhists would say is the ultimate, true nature of reality.

Unified mind versus innate enlightened potential

Professor Hoffman puts the Cognitive Science take on this in different — yet similar — terms:

“I call it conscious realism: Objective reality is just conscious agents, just points of view. Interestingly, I can take two conscious agents and have them interact, and the mathematical structure of that interaction also satisfies the definition of a conscious agent. This mathematics is telling me something. I can take two minds, and they can generate a new, unified single mind.” [3]

It’s not just Quantum Physics, Cognitive Scientists and Neurology that tend to align smoothly with Buddhist teachings on mind and reality; psychology has long aligned neatly with Buddhism. It’s well known that psychology and psychiatry have long borrowed meditation methods from Buddhist practice, notably Mindfulness, but the alignment goes far beyond practice into visual symbolic language, dream-activity, and the concepts of archetypes.

One concept in Buddhism is Shunyata, variously described as Emptiness or Oneness. When the ego is removed, there is oneness.When the ego is introduced, phenomena arise from the observer (with the ego).

Psychology meets Buddhism: innate enlightened potential

“Perhaps the most significant experience of the tantric path, therefore, is the introduction to a deity that will embody our innate enlightened potential, the seed of our eventual wholeness.” — Robert Preece [2]

Not understanding the true nature of deity, some people view the virtual pantheon of deities in Vajrayana Buddhism with a suspicious eye. Buddhism, we are taught, is not theistic. Without exploring further, some people might view Vajrayana as “superstitious” or “pagan.” For this reason, Western practitioners are quick to add the label: “Meditational Yidam” to the deity, implying a construct of the mind. Of course, mind-perception is the whole point. Lifelong practitioners, on the other hand would find this too apologetic; there is room enough in a world of illusory perceptions (our world) for both atheism and theism.

In both psychology and Buddhist practice, we meditate. Here, in deity meditation, a wrathful deity is visualized. Visualization of deity helps us overcome incorrect conditioning of illusory phenomena. Becoming the deity, then dissolving the deity to “Clear Light” or “Emptiness” helps us overcome the conditioning that prevents Oneness or Emptiness.

I attended one deity teaching with a well-known Tibetan teacher where he actually laughed and said, “Yes, I am a pagan.” He was speaking to a room of advanced students, and we all laughed along, understanding his deeper meaning. Later, this same teacher said, “Buddhists are atheists.” How confusing is that?

Visualization or Imagination?

Whichever term we use, it is irrelevant. The imaginary friend we had as a child seemed real to us — and so it was, until our parents convinced us otherwise. The lesson of the child is not one of faith — but of imagination. When you vividly imagine the Enlightened qualities of a Buddha — create “conscious realism” to awaken the seeds. We call it Deity Yoga in Vajrayana Buddhism.

Deity Yoga (union) is a very profound practice. Robert Preece explains:

“The deity in Tantra can be understood as a gateway or bridge between two aspects of reality. Buddhism has no concept of a creator God… the deity is a symbolic aspect of forces that arise on the threshold between two dimensions or reality, or two dimensions of awareness. In Buddhism we speak of “relative truth,” the world of appearances and forms, and “ultimate truth,” the empty, spacious nondual nature of reality.”

Self generation visualization is one of the many “yogas” in each unique Yidam practice.

Theism and atheism — do they even matter?

So, the two extremes — theism and atheism — do they really matter? Thich Nhat Hanh, the great Zen teacher, explained what Buddha really taught:

“The Buddha always told his disciples not to waste their time and energy in metaphysical speculation. Whenever he was asked a metaphysical question, he remained silent. Instead, he directed his disciples toward practical efforts.”

All phenomenon are dependent-arising in Buddhism.

So, what then, does the newcomer to Buddhism make of countless Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, Protectors and Yidams? They aren’t creator gods. They aren’t eternal, self-aware beings. It’s fine to view them as such if that’s your faith, but at the end of the day, it doesn’t matter. Shakyamuni Buddha, speaking in the Cula-Malunkyovada Sutta, was very clear on how he viewed these cosmic questions:

“So, Malunkyaputta, remember what is undeclared by me as undeclared, and what is declared by me as declared… And why are they undeclared by me? Because they are not connected with the goal, are not fundamental to the holy life. They do not lead to disenchantment, dispassion, cessation, calming, direct knowledge, self-awakening, Unbinding. That’s why they are undeclared by me.”

In other words, the idea of creation, gods, heaven, eternity — and even the question “Does Buddha exist after death” — on these subjects, Buddha would not speak. Clinging to these notions become another form of attachment. [For a story on the “Four Questions the Buddha Would NOT Answer and Why, see here>>]

Visualizing the self as the deity is a Vajrayana practice that helps us understand the illusory nature of relative phenomenon.

The psychology of deities

Why, then, is Vajrayana — a path that embraces Yidams or heart deities as a method — considered an advanced practice, rather than a superstitious one? The answer lies in psychology.

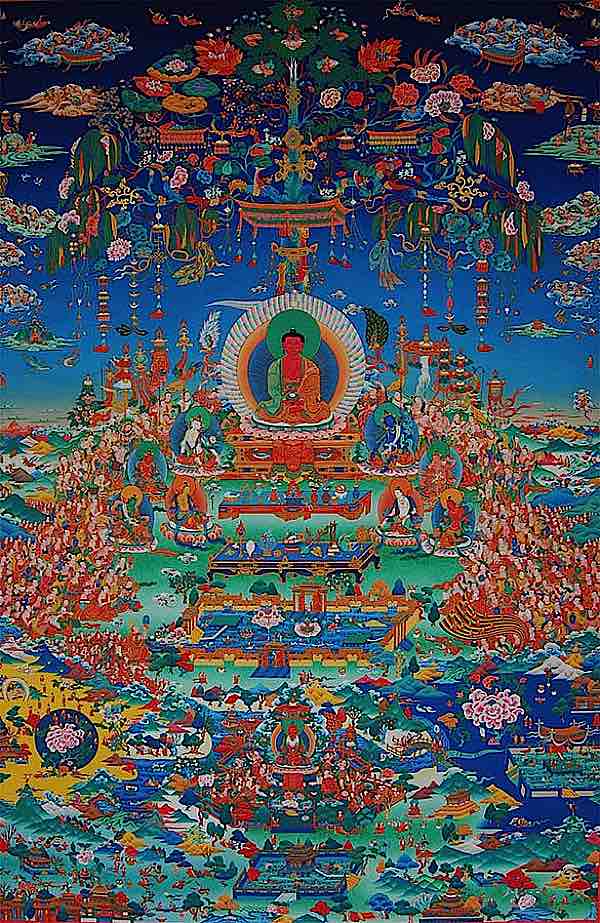

A complex visualization of Amitabha and other deities in Sukhavati.

Rob Preece, in The Psychology of Buddhist Tantra, explains:

“The intention of Tantra is to gradually awaken the seeds of our innate wisdom as a source of health, power, love, and peace that can then live through every aspect of our lives. We can engage in life more fully and confidently because we are in a relationship to our true nature personified in the deity.”

When teaching deity practice, teachers often use language like “use your imagination” or “visualise the deity.” In other words, don’t expect a tangible deity to suddenly appear before you. That isn’t the point or the goal.

One of the reasons Tantra uses teacher-transmission or “initiation” as a control it to ensure students have the right understanding of their practices — to prevent superstition.

Visualizing Deities is not about worship

Why, then, does Vajrayana focus so extensively on the details and appearances of these deities, if they aren’t trying to develop a worshipful wonder? Most visualizations in Vajrayana are challenging to say the least. The “gods” are magnificent and exotic and wonderful: some beautiful beyond conception glowing with divine light; some complex, with a hundred arms and implements; some wrathful and monstrous and awe-inspiring, surrounded by an aura of flames.

Palden Lhamo embraces the wrathful nature — our Shadow in psychology.

Do we “conjur” these gods to then bow down and worship them? No, in Vajrayana, we take them into ourselves. We see the deity dissolving and entering into us. Or, we visualize ourselves as the deity, then we see ourselves dissolve to Emptiness. Why work so hard if we are only going to dissolve the whole thing into emptiness? After all, these visualizations are beyond challenging. Why, then, give them up after all that hard work.

The answer lies, in part, in the concept of Buddha Nature. [For a feature on Buddha Nature, see this story>>] Psychologist Rob Preece explains:

“Our innate Buddha potential is said to be like a priceless jewel buried beneath our home, while we live our lives in ignorance of it. As a result, we flouder, lost in endless confusion.”

Deity practice helps us awaken to our buried treasure, the jewel of our own Buddha Nature — and much more.

At the ultimate level, oneness.

The point of practice: union with deity; union with higher self

The language of the mind is symbols and imagery. Developing concentration, clarity and stability — and correct understanding of relative phenomenon — are some of the key reasons to practice what is known as “Deity Yoga.” Deity Yoga literally means “union with Deity.”)

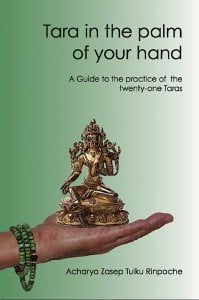

Zasep Rinpoche is the author of Tara in the Palm of Your Hand, available here on Amazon>>

Venerable Zasep Rinpoche explains: “Everybody has the same problems. Everyone has the same type of difficulties, struggling. But, this is practice. This is the path. This is how it is. Don’t blame yourself, don’t blame anybody, just keep practicing. This is how everybody has to learn.

“So, when you have that, it’s like a child, a little child, fantasizing about toys. You go to the toy shop, and all you think about are toys. Like a little boy with his toy truck.

Automatically, boom, your mind is gone. Drawn in. Because you want this, you like this, you are so excited. Yogis, or Yoginis, should have this kind of excitement or passion.

Short video teacher on “Visualizing Your Meditation Yidam”

Yidam visualization is “not easy”

In a teaching session on deity, Zasep Rinpoche said, “visualisation is not an easy one to do unless you have a good imagination.” [See embedded video below, “Visualizing Your Meditational Yidam.”]

“Some people feel, how can I do this visualization? My visualization is no good at all. I can’t see anything. My meditation is not good, concentration is not good, I don’t have clarity, I have no stable mind, my mind is all over the place and so on and so forth.”

What is important in Yidam practice is to practice daily, and not to lose sight of the goal — to catch a glimpse of Oneness, or Emptiness, of reality as it truly is without the observer-observed.

NOTES

[1] Max Planck, 1944; Das Wesen der Materie [The Nature of Matter], speech at Florence, Italy (1944) (from Archiv zur Geschichte der Max-Planck-Gesellschaft, Abt. Va, Rep. 11 Planck, Nr. 1797)

[2] The Psychology of Buddhist Tantra, Robert Preece